This year, JPPI’s Pluralism Index survey was conducted under the shadow of the coronavirus pandemic, and immediately after Israelis had been subjected to their third round of tense and difficult elections in the space of a year.

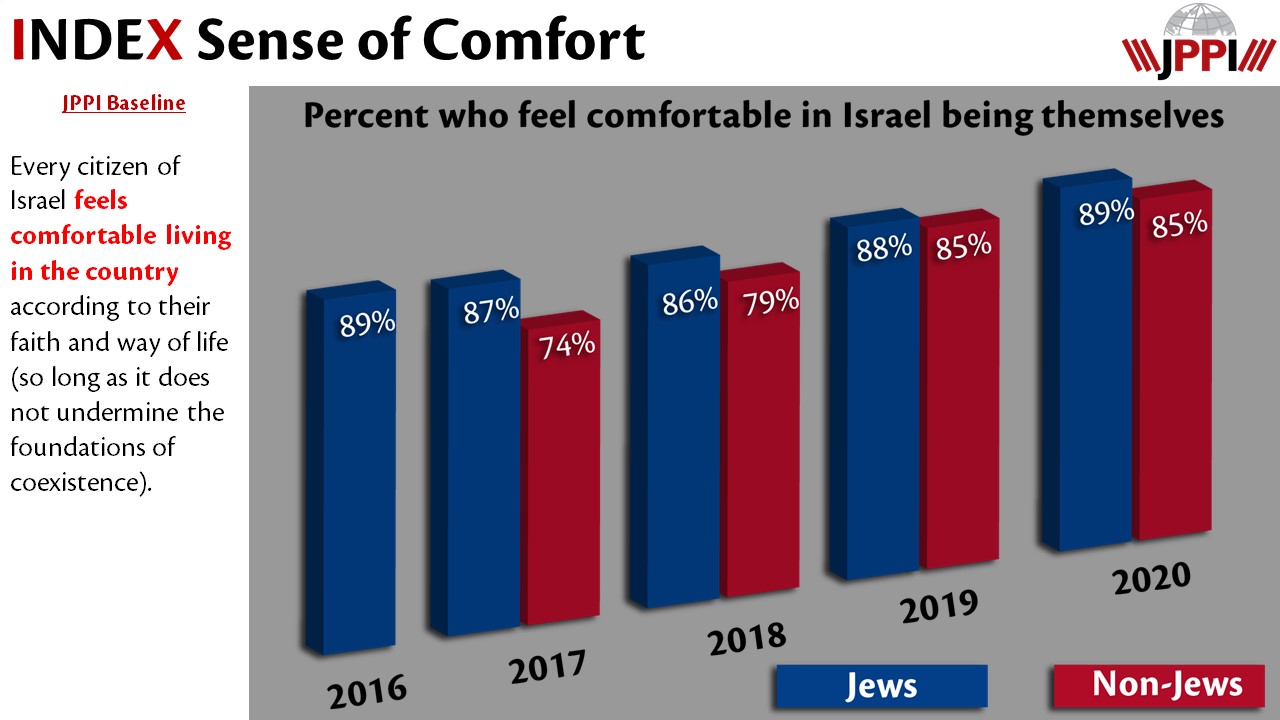

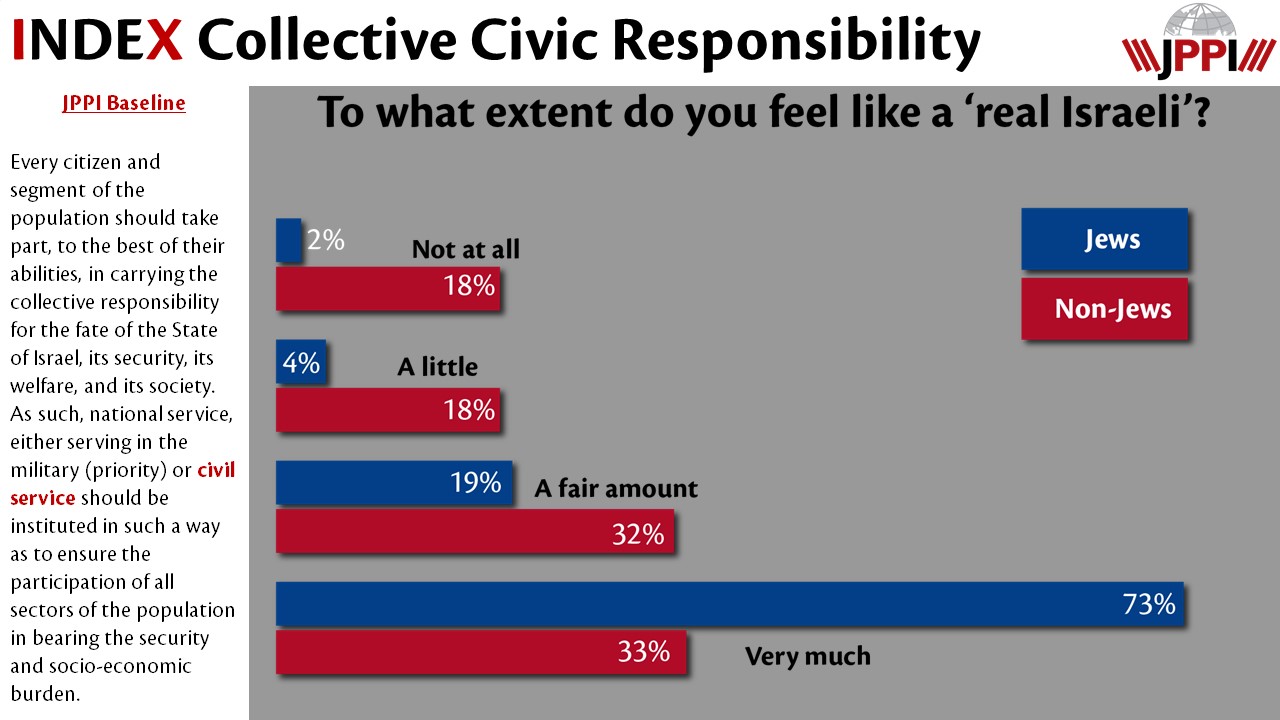

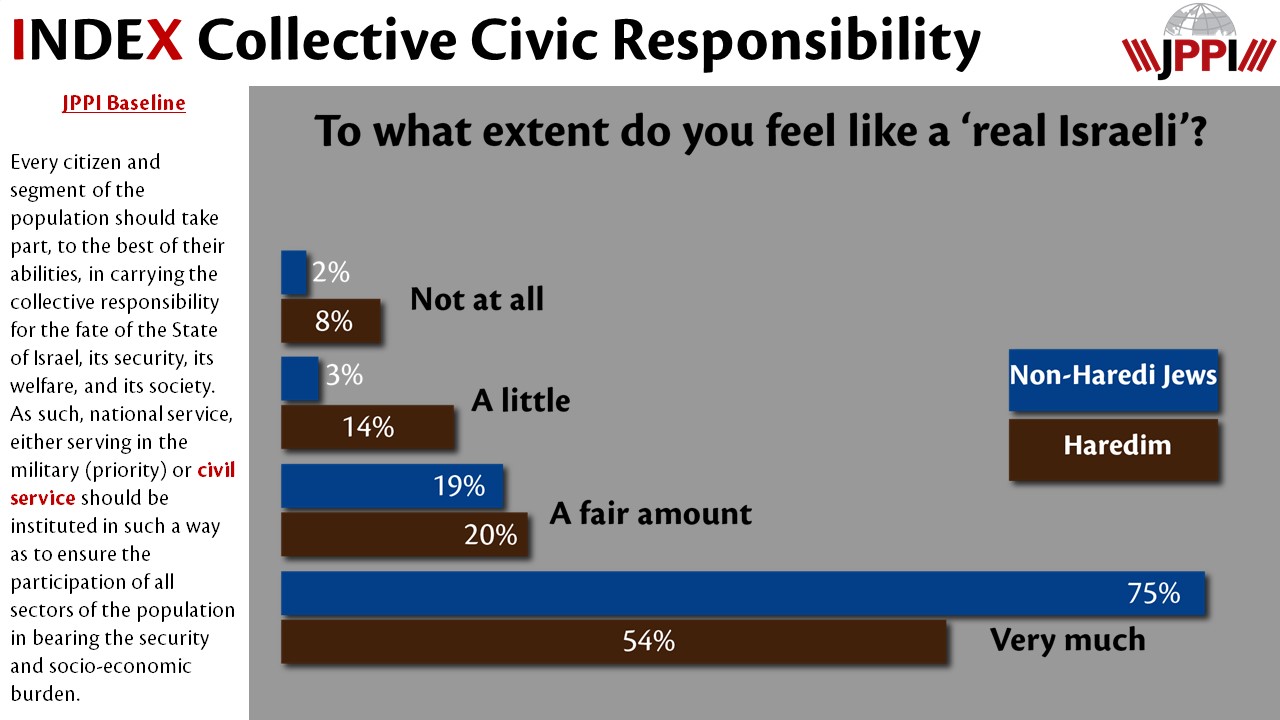

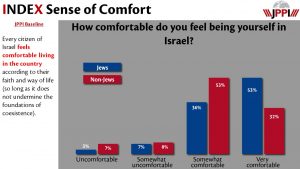

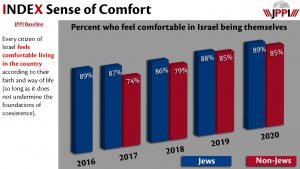

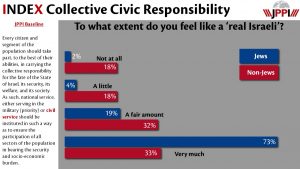

The survey reveals that these events have not, at least up to this point, significantly undermined the Israeli sense of cohesion. The “comfort index,” which looks at whether Israelis feel “comfortable being themselves in Israel,” there was virtually no change compared with last year. Similarly, most Israelis, both Jews and non-Jews, feel like “real Israelis,” at least to some degree.

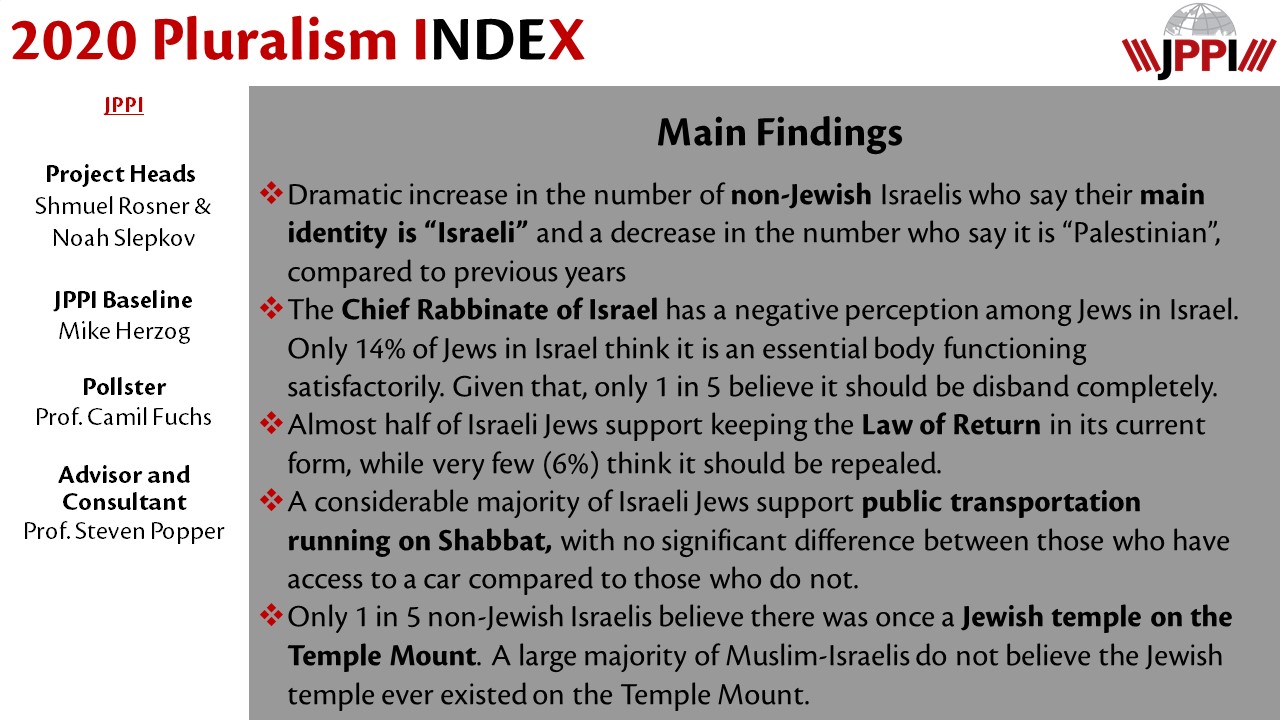

Below are a few of the findings from this year’s Pluralism Index, followed by a detailed discussion of their significance:

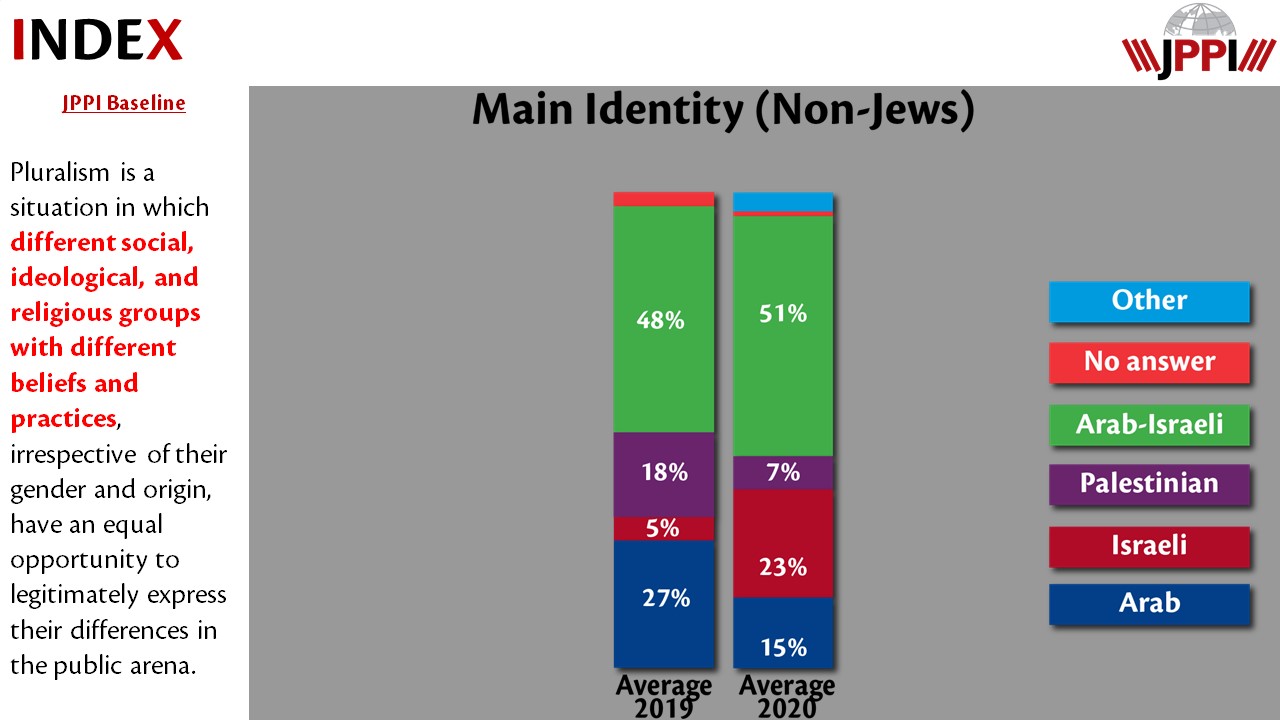

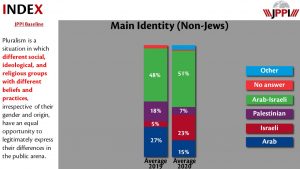

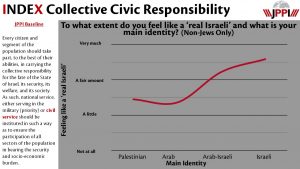

- A dramatic increase, compared with last year, in the percentage of non-Jews who consider their primary identity to be “Israeli,” and a concurrent sharp decline in the percentage of those who define their identity as “Palestinian.”

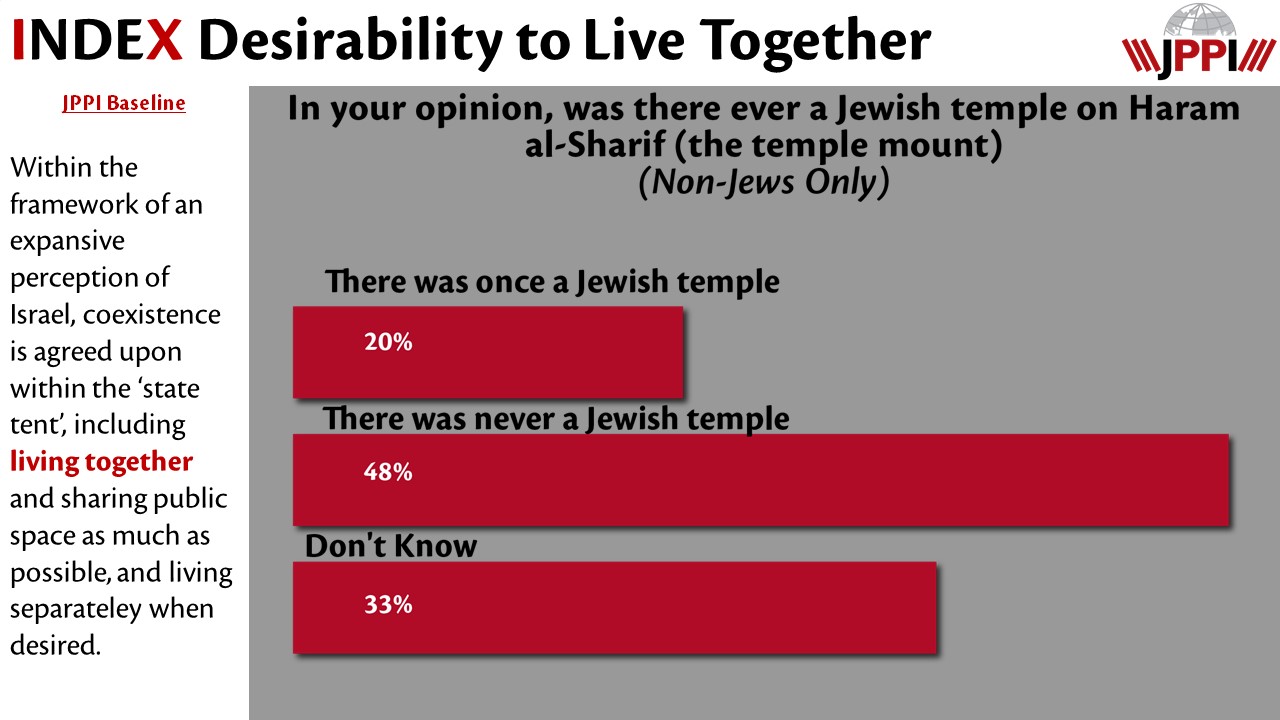

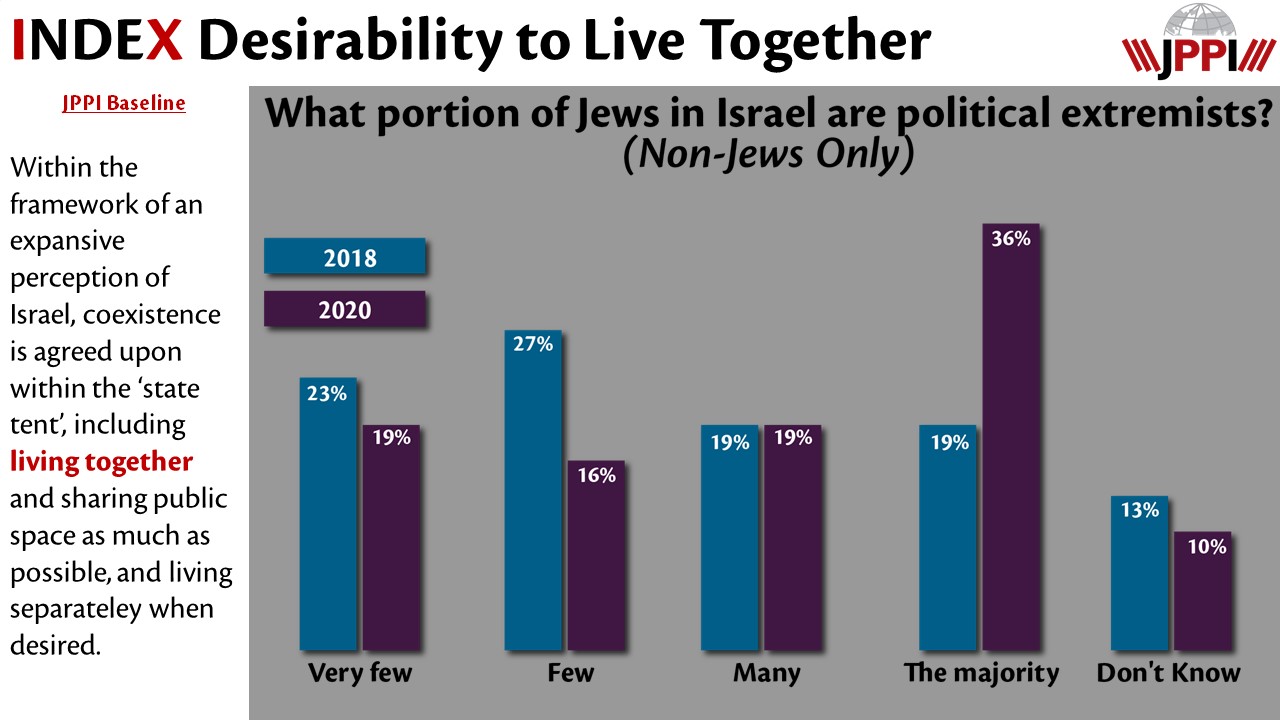

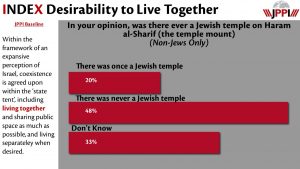

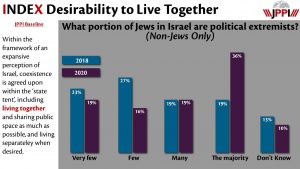

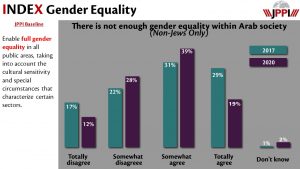

- At the same time, only one out of five non-Jews believes that there was once a (Jewish) temple on the Temple Mount. A substantial majority of Muslims in Israel believe that there was no temple on the Temple Mount. Additionally, most non-Jews think that a large proportion of, or most, Israeli Jews are “extremist.”

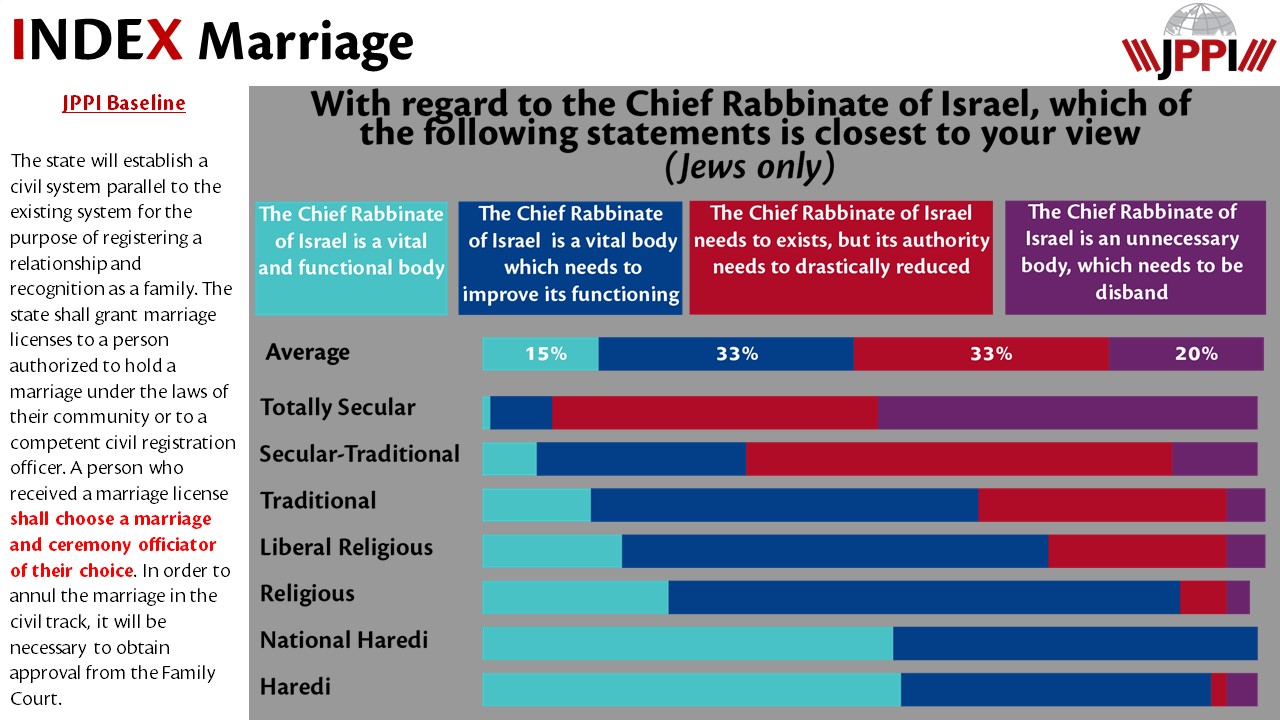

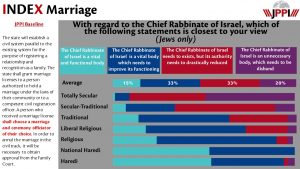

- The Chief Rabbinate’s negative image in the eyes of Israeli Jews. Only 14% of Israeli Jews feel that the Chief Rabbinate is a vital, well-functioning institution. However, only one in five Israeli Jews supports dissolving the Chief Rabbinate.

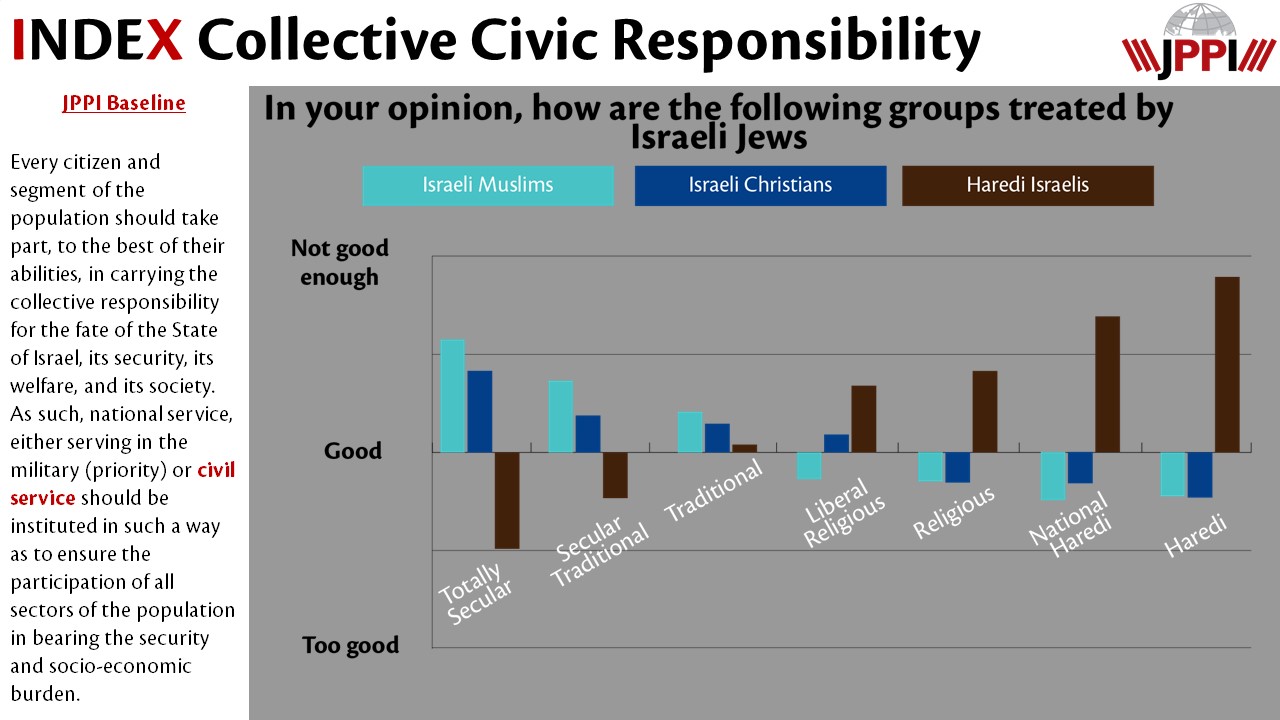

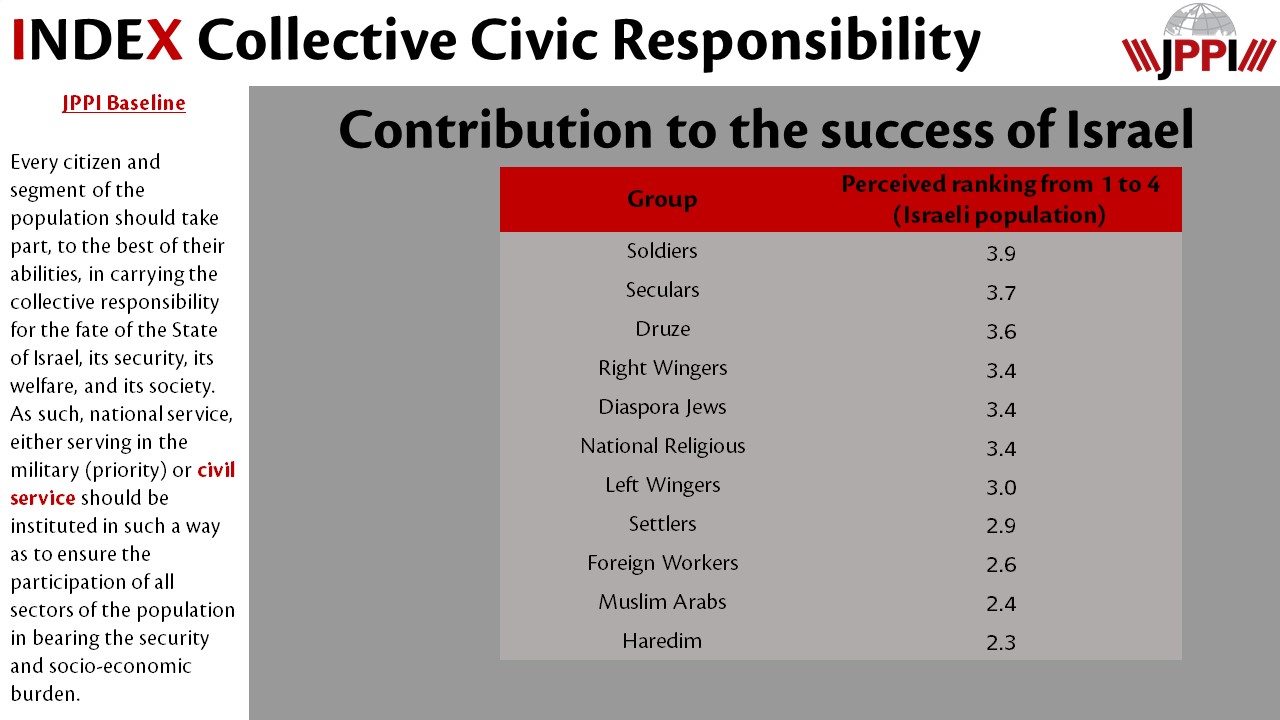

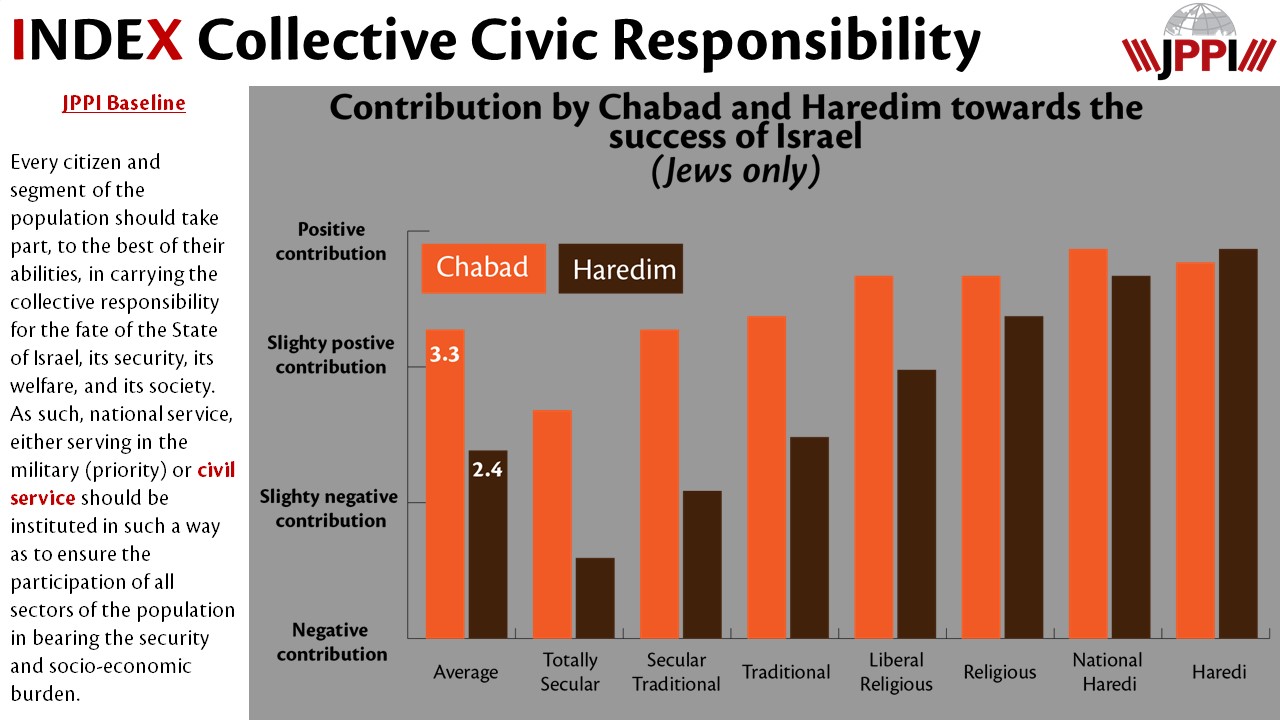

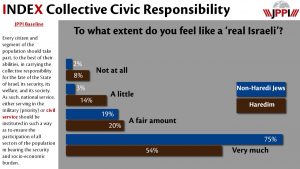

- Other findings attest to the Haredi (ultra-Orthodox) sector’s negative image regarding its contribution to the state. Most secular Israelis feel that Israeli society treats the Haredim too well.

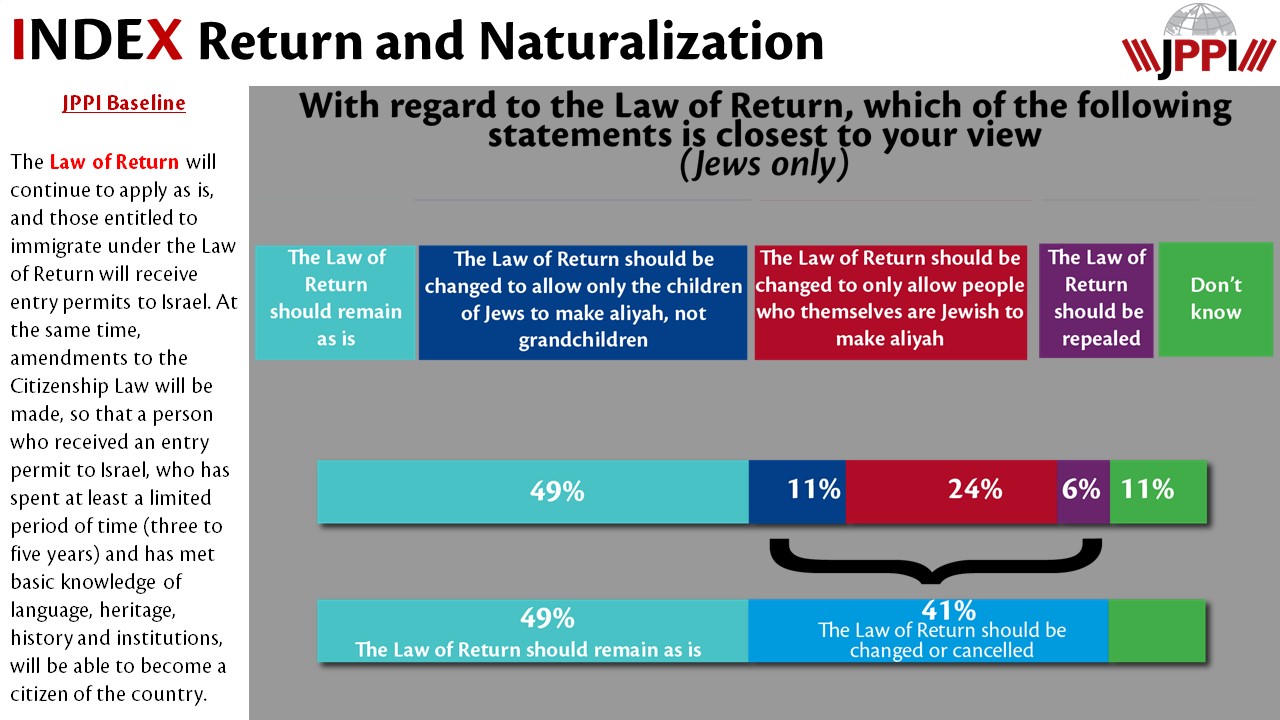

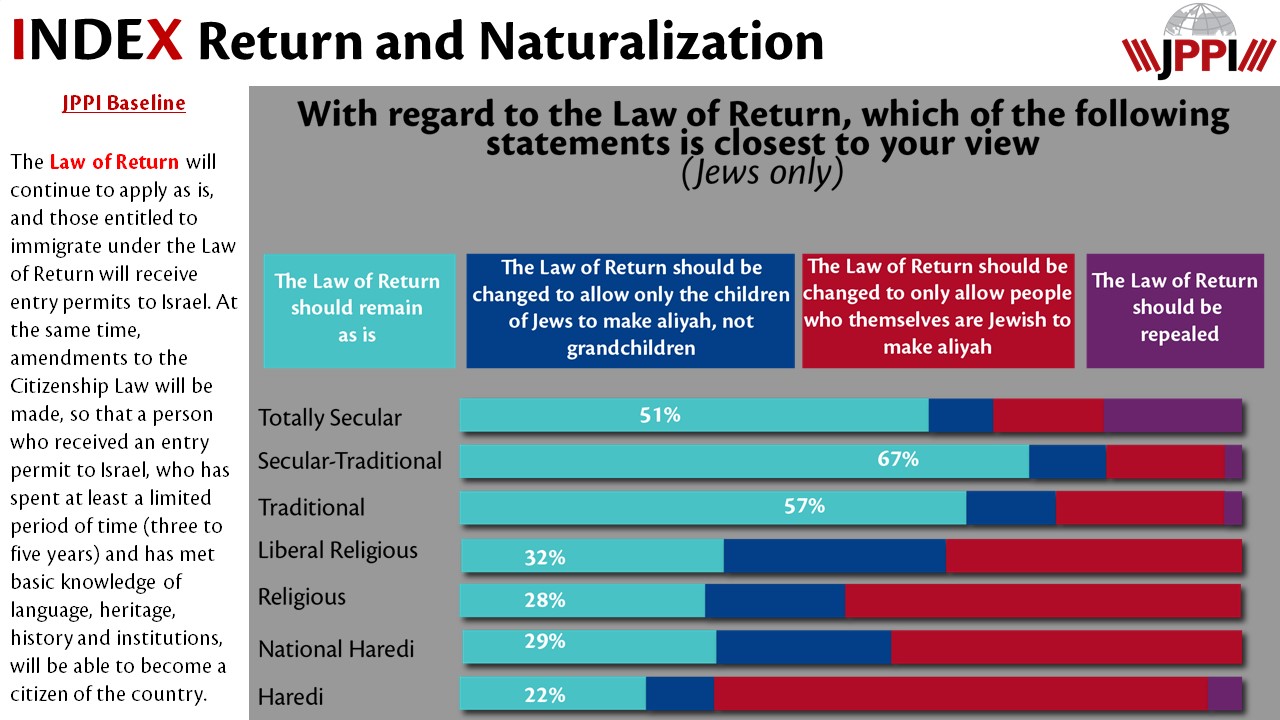

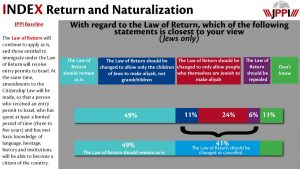

- Nearly half of Israeli Jews think that the Law of Return should remain in its current form. Most of the others feel that sections of the Law should be modified to stiffen eligibility criteria. Very few (6%) think the Law should be repealed.

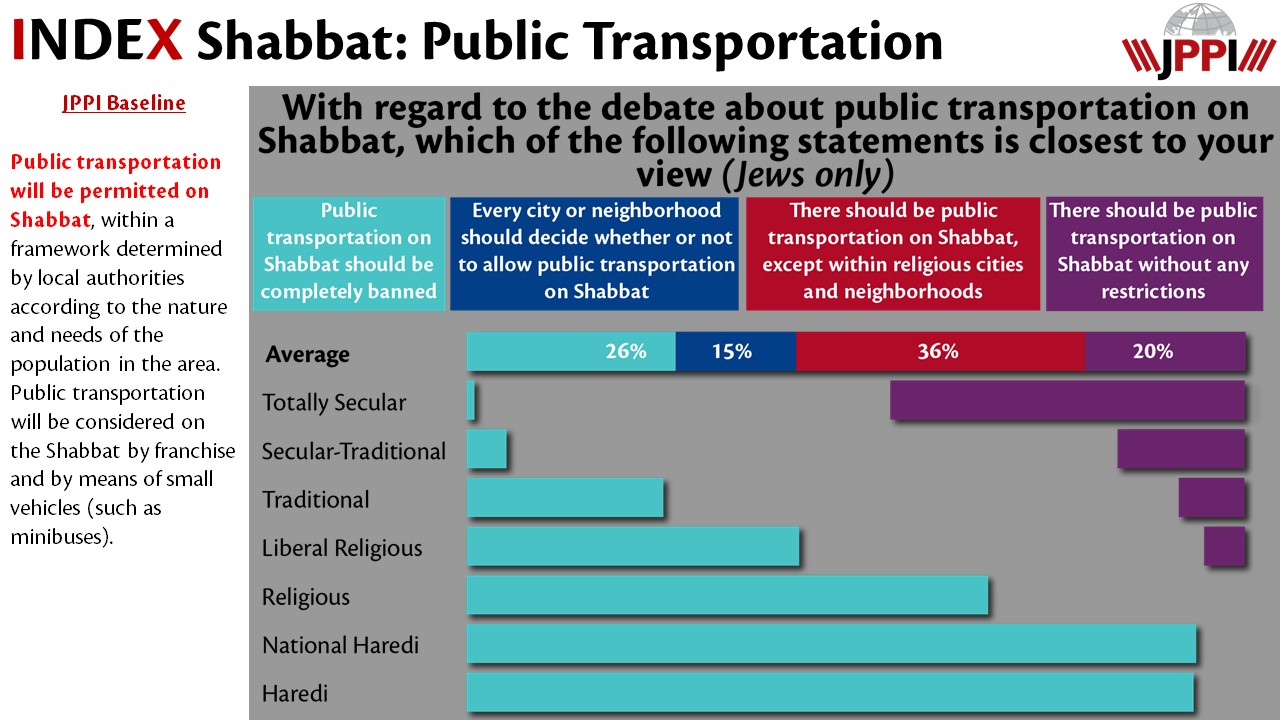

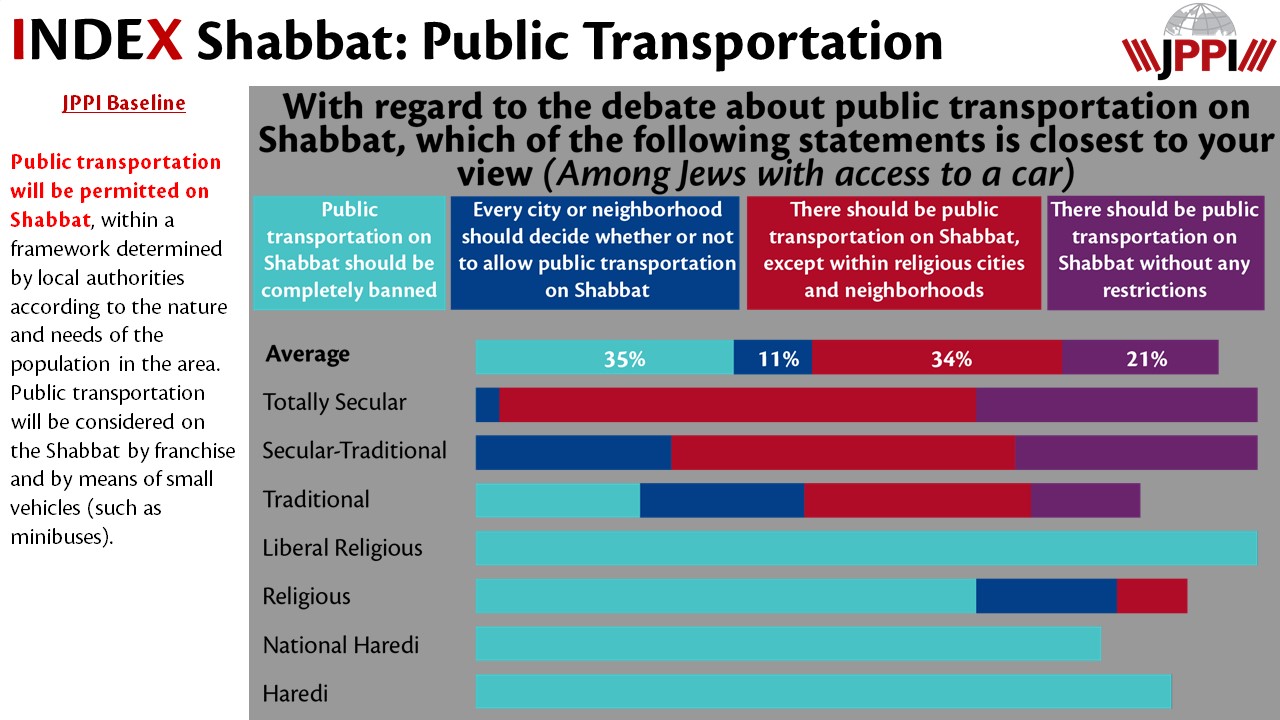

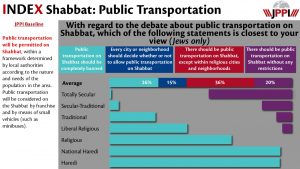

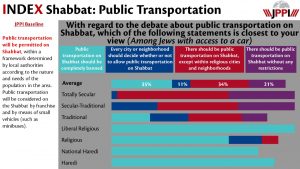

- A substantial majority of Israeli Jews support the operation of public transportation on Shabbat. Car ownership (or non-ownership) has no real impact on Israeli opinions regarding this issue.

2020 Index

Click here to download the results of the survey in excel

Index Presentation

Introduction

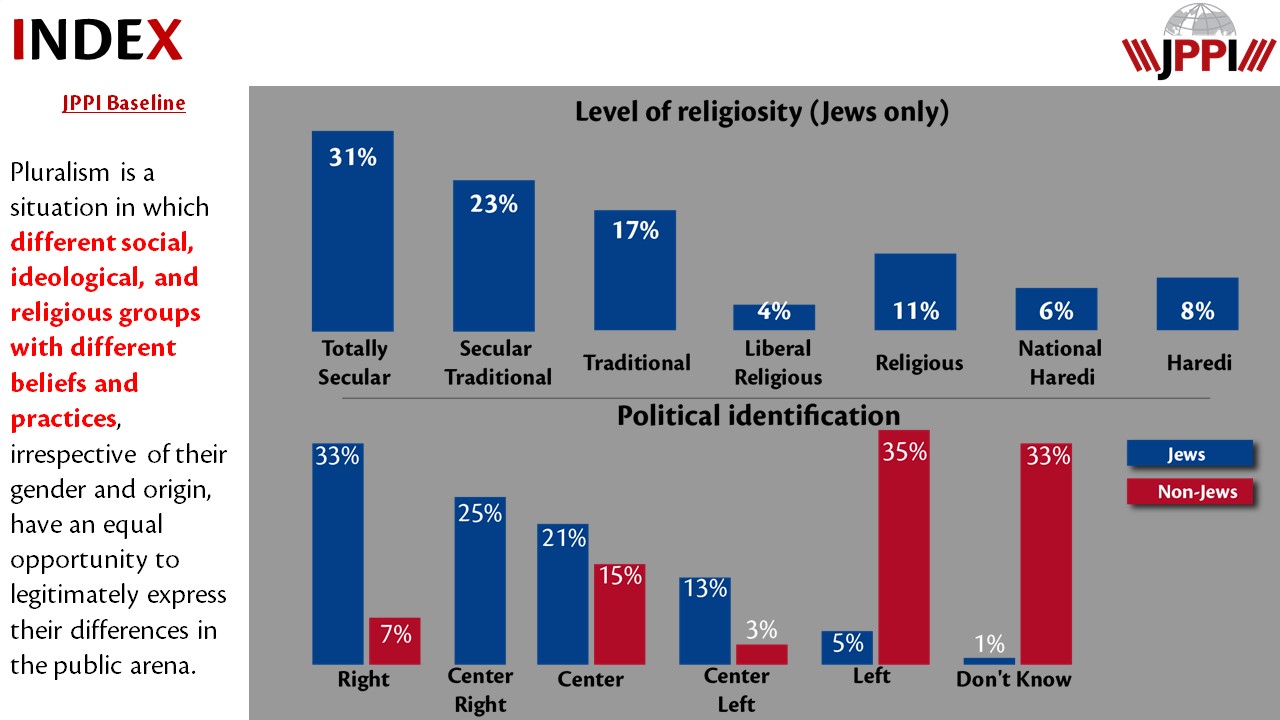

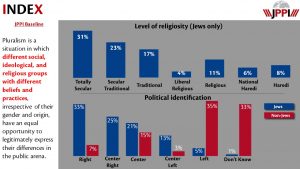

This is the sixth year the Jewish People Policy Institute is releasing its annual Pluralism Index, and the fifth year in which the Index is based, among other things, on a comprehensive opinion survey. As in past years, the survey included Jewish and non-Jewish respondents. in the case of the Jewish respondents, it drew on the large respondent base of the JPPI’s comprehensive 2018 Israeli Judaism.

The Pluralism Index consists of a set list of topics with a predetermined baseline, a kind of snapshot that strikes a balance between the attitudes and desires of different groups in Israeli society. Each year, relevant data are positioned against this baseline, making it possible to study evolving trends and gauge the degree to which Israeli reality approaches or diverges from the baseline.

This year’s survey, like last year’s, was conducted by Professor Camil Fuchs of Tel Aviv University. The Index project is administered by JPPI’s Noah Slepkov and Shmuel Rosner. The Index baseline was written by JPPI Senior Fellow Brig. Gen. (Res.) Michael Herzog. The following JPPI fellows contributed to the analysis: Dr. Shlomo Fischer, Amb. Avi Gil and Dr. Dov Maimon.

The Coronavirus Crisis

The health and economic crisis in which Israel and the world were mired while the Pluralism Index was under preparation, had no direct bearing on the Index. The purpose of the Index is to identify long-term trends, not to respond to short-term developments. Nevertheless, crises often generate turning points whose impacts persist after the crisis has passed. In this context, it is worth looking at certain Index data relating to groups that have figured prominently in the current crisis.

Two such statistics relate to the attitude of non-Haredi Israelis toward Haredi Israelis. Over the course of the coronavirus crisis, much attention has been paid to the way Haredi society has coped with the government issued directives that have necessitated severe modifications of daily life in Israel. Haredi society has relatively little trust in the major state institutions, and this has been reflected in the fact that major subgroups within it were slow to implement guidelines issued by the Ministry of Health and other governmental decision-makers.[1] The conspicuousness of these groups – the need to attend to them separately, their infection rates, and the necessity of devoting special resources to them – may have an impact on both the internal Haredi system (leadership, values, attitudes toward state institutions) and on the attitudes of other Israelis toward the Haredim.

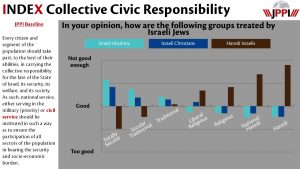

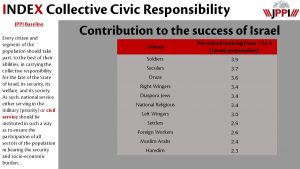

Each year, the Pluralism Index assesses attitudes toward different groups within Israeli society, and the Haredim consistently place at the bottom of the “contribution to the state” scale (this doesn’t mean they don’t contribute, but rather that other Israelis perceive them as not contributing). They rank low on the scale again this year, and when we adjust for the responses of Jews and non-Jews, the Haredi contribution to the state is perceived as the lowest of all the groups assessed (the current Index looked at 17 groups; for most of them, there was no real change from last year).

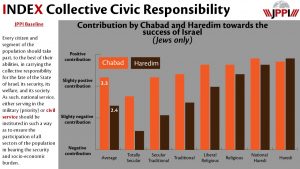

This year, the “contribution to the state” query was supplemented by a more detailed question aimed at discovering whether Israelis feel that Jewish societal attitudes toward various minority groups are “not positive enough,” “positive,” or “too positive.” On this question (as on the “contribution to the state” question), there was a real disparity in the responses according to the respondent’s place on the religiosity scale. Half the secular population feels that attitudes toward Haredim are too positive. In contrast, half of the Masorti (traditionalist) and religiously observant (non-Haredi religious) respondents indicated that attitudes toward the Haredim are positive, or not positive enough. That is, they think that current attitudes should be maintained, or improved. As noted, these data were gathered during, and against the background of, the coronavirus crisis. They reflect attitudes toward the Haredim during a given period characterized by the tumult of the crisis. The data need to be reexamined in the coming years, to determine whether, and to what degree, they changed after the crisis, and also in relation to developments within Haredi society itself, if any.

Religion and State

In the three election campaigns held in Israel over the past year, points of disagreement on issues of religion and state were often prominent. This was true of questions relating to budget allocations or Haredi Torah studies, laws that limit public transportation on Shabbat/holidays and that regulate kashrut, and the authority granted by the state to the Chief Rabbinate with regard to marriage and burial. In the past year, at least until the start of the coronavirus crisis, which forced Israelis to seclude themselves in their homes, real change could be discerned regarding the operation of public transportation on Shabbat – change initiated and funded by municipalities across the country. This development emerged during the period when the national political discourse was preoccupied with election issues; municipalities and local councils saw an opportunity to create facts on the ground.

It has been known for some time, and proven by numerous opinion polls, that the Israeli public supports public transportation on Shabbat.[2] However, the common claim that public transportation is of special importance to Israelis who lack access to private cars, has not been evaluated in depth. The JPPI index indicates that this argument is specious, for two reasons. First, a large proportion of those with no access to private cars are Israelis who vehemently object to public transportation on Shabbat (mainly Haredim). Second, among those that support full or partial transportation on Shabbat, there is no significant difference between car owners and those without access to private vehicles. That is, most Israelis take principled stands on the issue of public transportation on Shabbat – stands that are rooted, not in their specific life circumstances, but in where they are situated along the religiosity spectrum. Fifty-six percent of the total sample and 52 percent of non-car-owners feel that public transportation should operate on Shabbat (either with no restrictions, or with the exception of religious cities and neighborhoods).

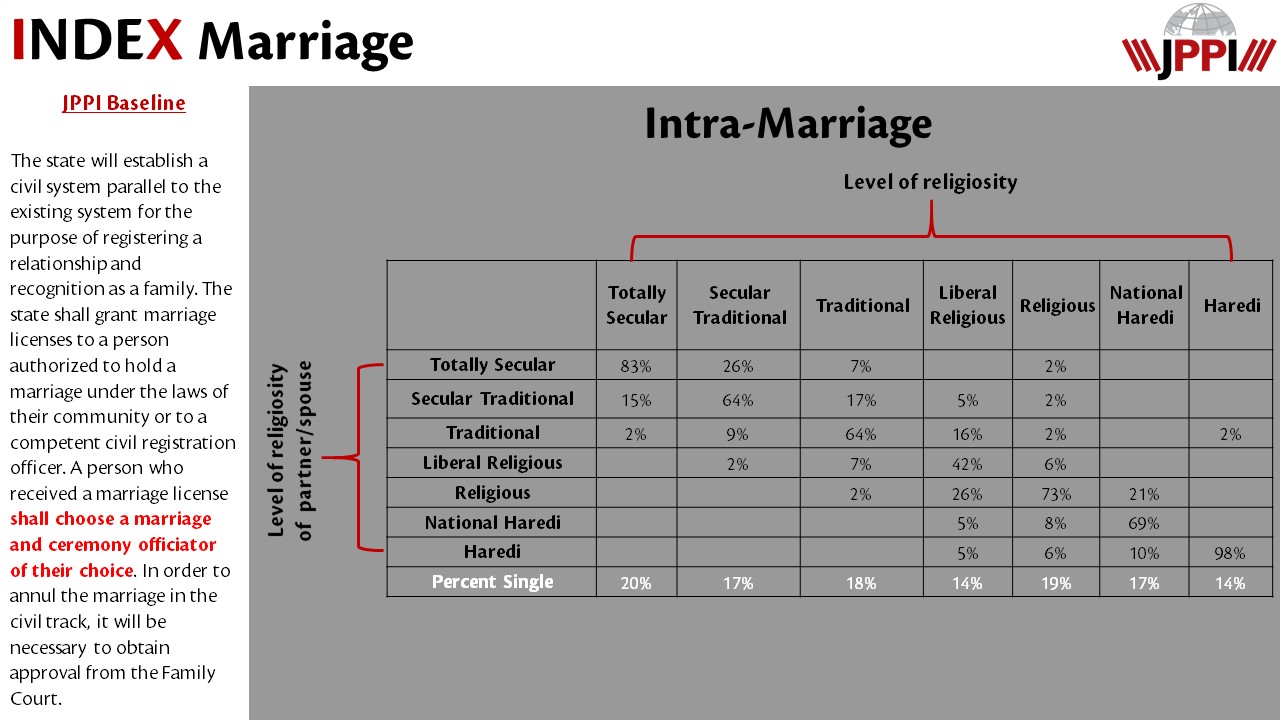

Where Israeli Jews are situated on the religiosity scale has a strong influence, but is not the sole determining variable, regarding their attitude toward the role and functional status of Israel’s Chief Rabbinate. This institution’s image has been tarnished for many years,[3] and the JPPI survey indicates that only a small percentage of Israeli Jews (14%) feel both that the Chief Rabbinate is necessary and that it functions properly. The rest of the Jewish population feels that its functionality should be improved, or that its powers should be curtailed, or that it should be dissolved entirely. When the respondents are divided into two groups – those who want a functioning Chief Rabbinate with powers, and those who either want a curtailed Chief Rabbinate or feel that the institution is altogether unnecessary – one finds disparities based on religiosity. Most of those who fall into the religiously observant category do not think the Chief Rabbinate functions properly but would like it to. In contrast, the majority of slightly-Masorti secular Jews feel that the Chief Rabbinate’s powers should be severely curtailed (not just that its functionality should be improved, 54%), while half of “totally secular” Jews (48%) think that the institution should be eliminated.[4]

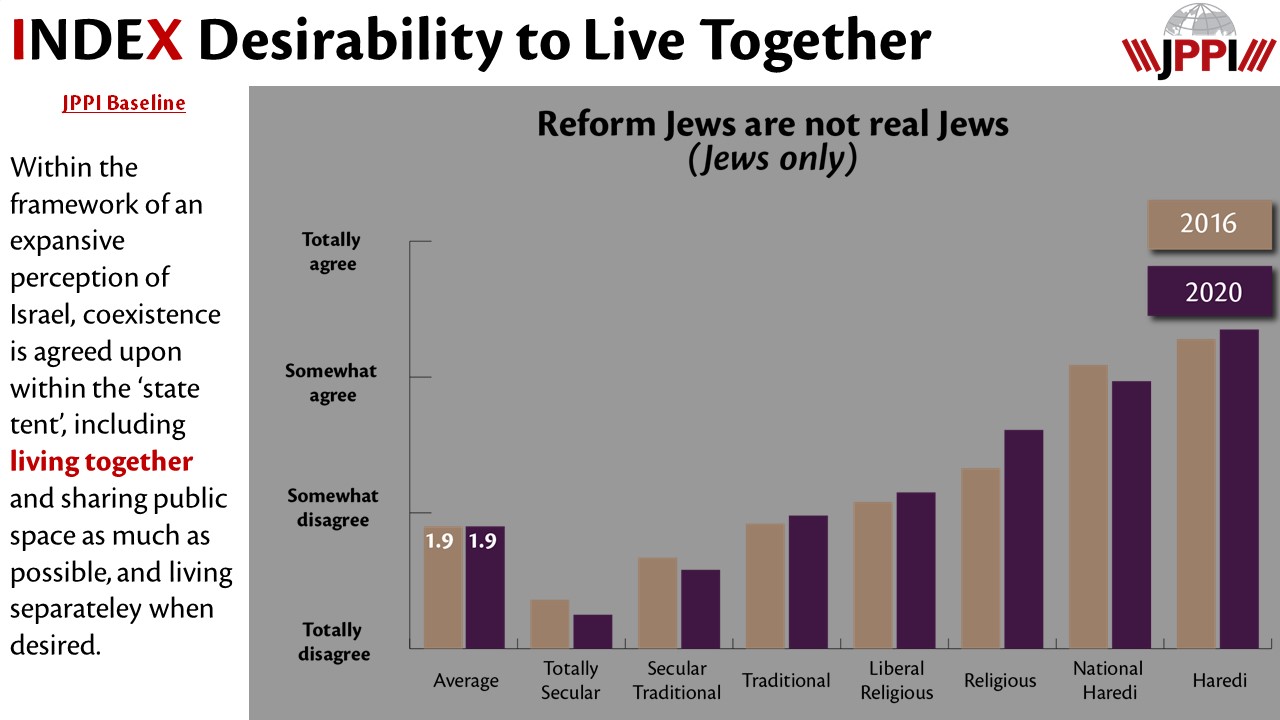

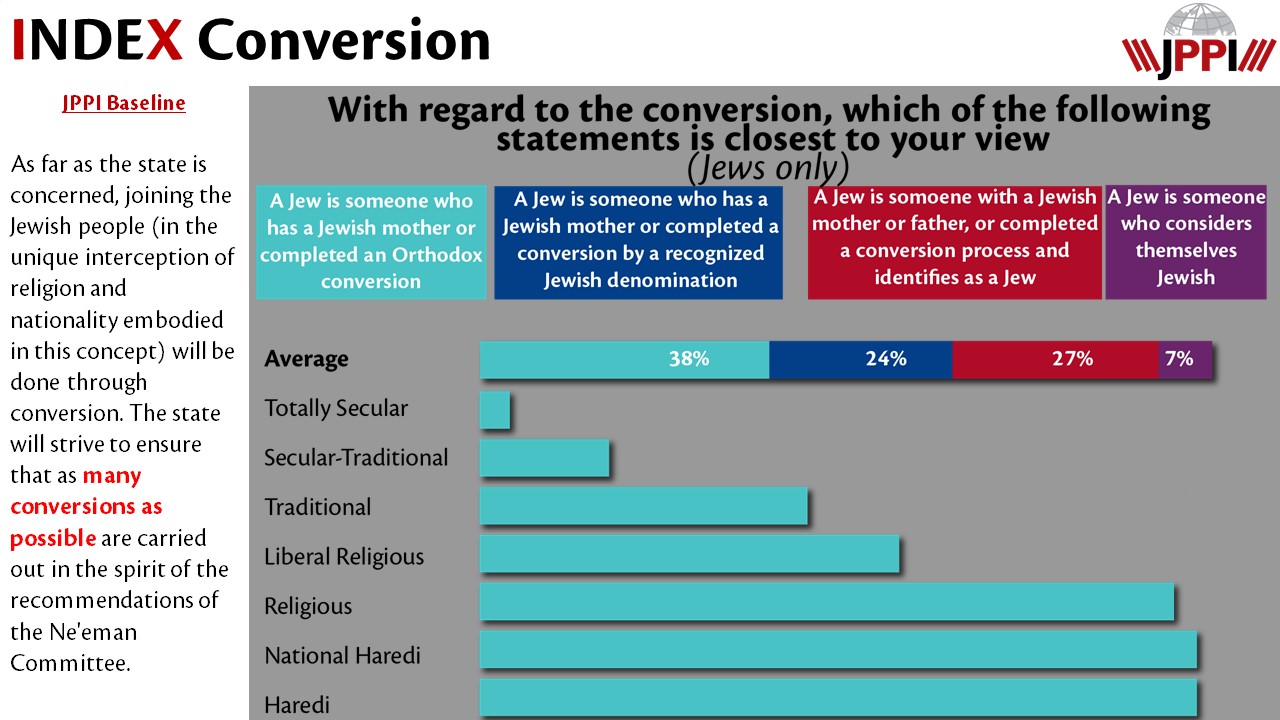

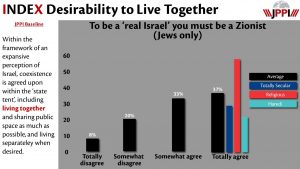

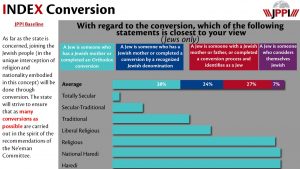

An interesting example of the gap between public opinion and Chief Rabbinate positions – the kind of gap that causes alienation from the institution and its leaders – can be seen in attitudes toward conversion. According to the JPPI findings, only a minority of Israeli Jews accept the Chief Rabbinate’s stance that a Jew is someone who was born to a Jewish mother or has undergone Orthodox conversion (38%). In essence, this position commands a majority only among Jews who self-define as religiously observant or Haredi. Among other Jews, there is a willingness to accept other, non-Orthodox, conversion channels; and secular Jews are willing to accept patrilineal descent. It should be noted, however, that only a small minority of Israeli Jews (7%) are prepared to accept self-definition only (someone saying that he or she is Jewish) as a sufficient criterion for Jewishness.[5]

Jews and Non-Jews

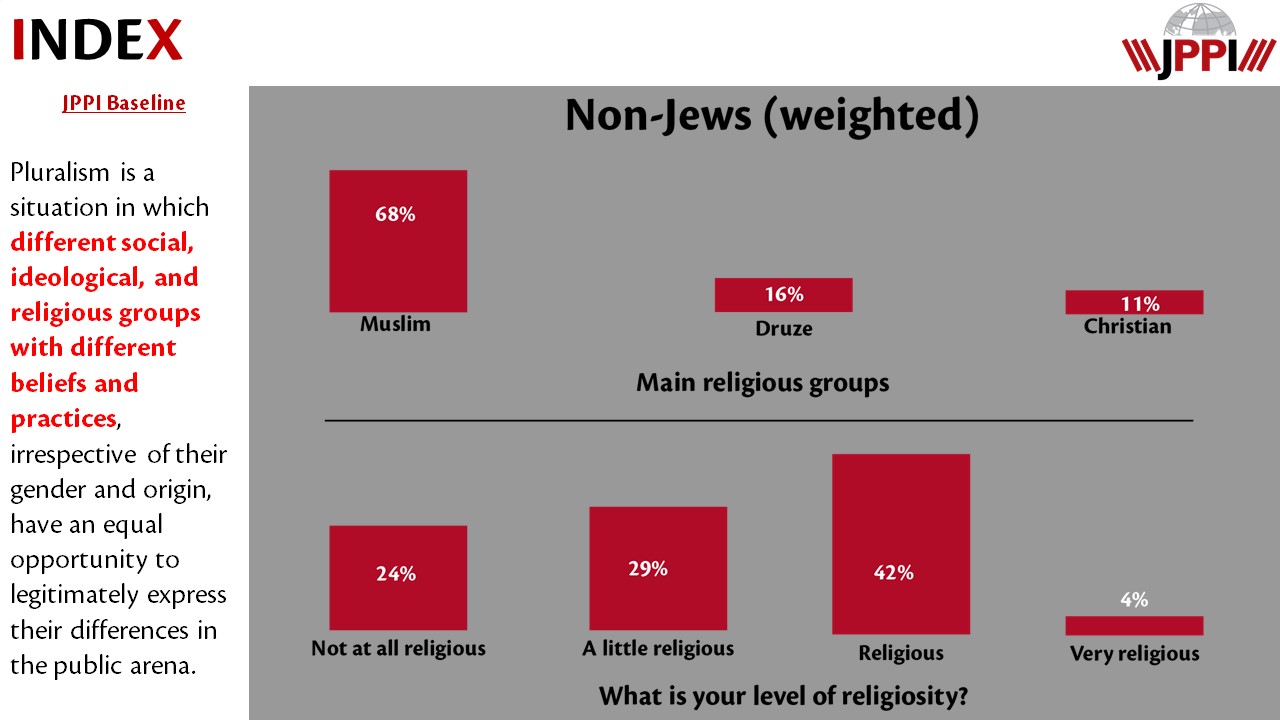

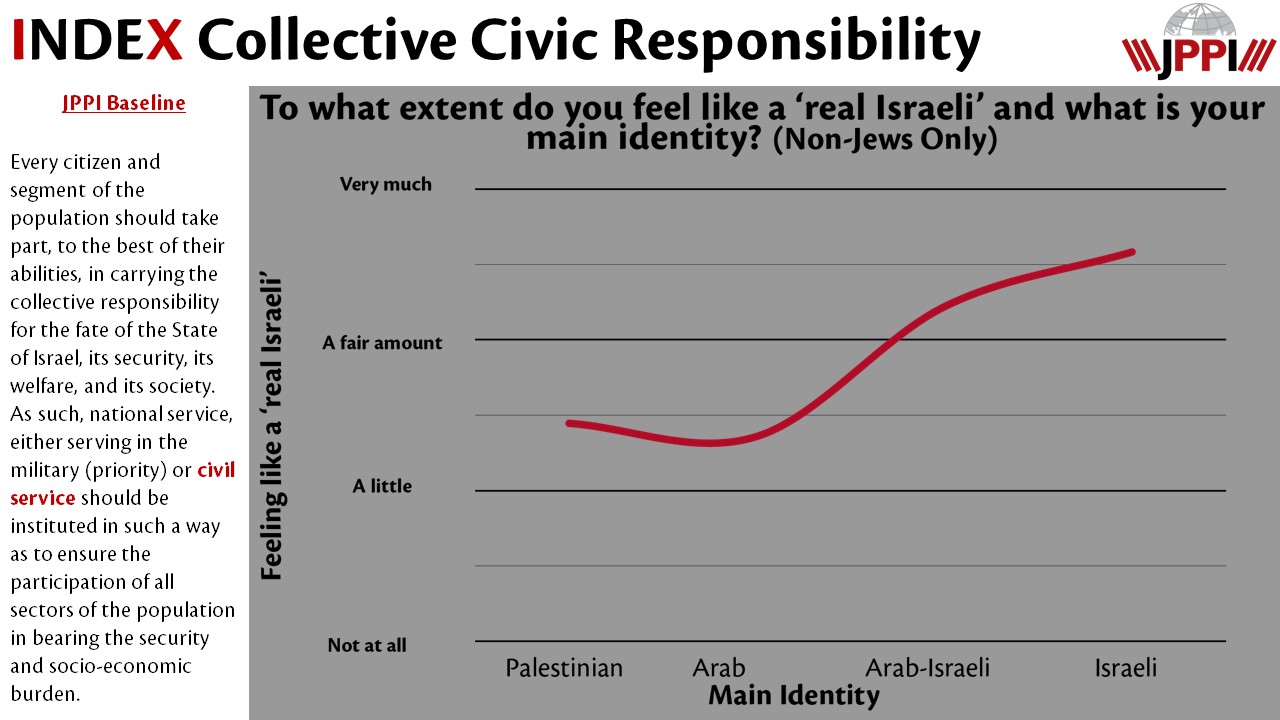

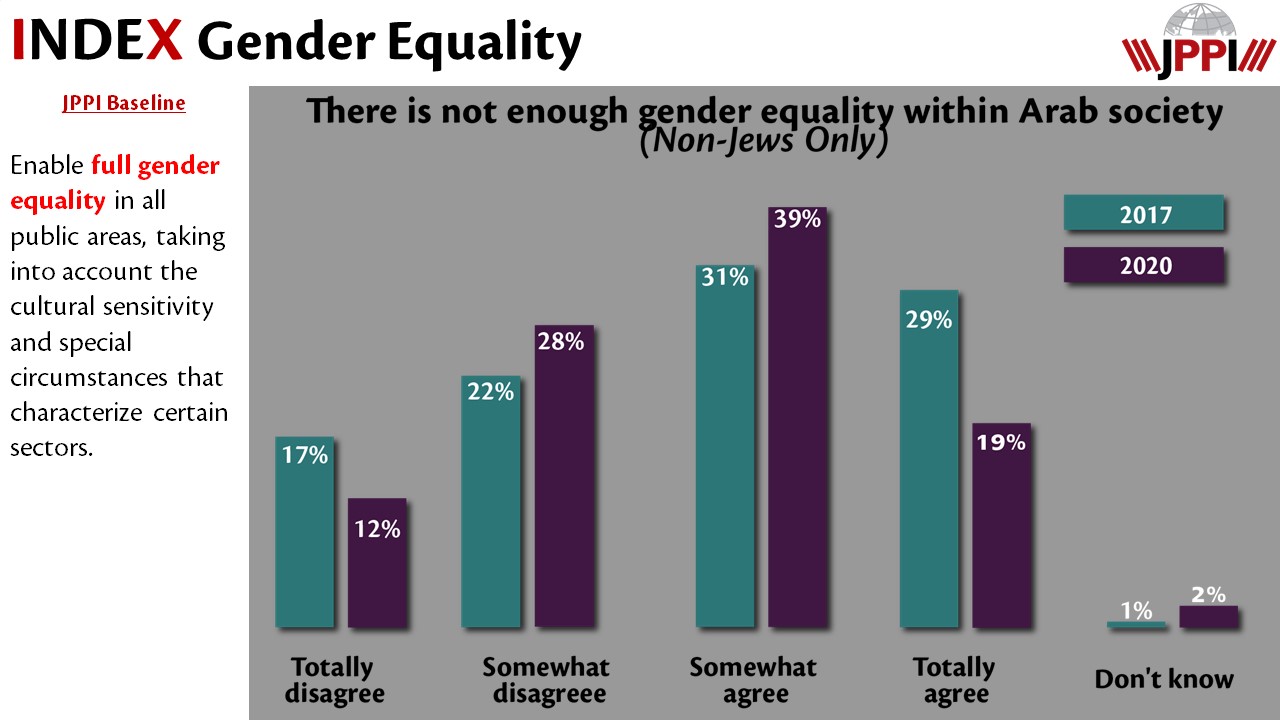

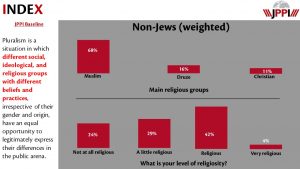

For the past four years, the Jewish People Policy Institute’s Israeli Pluralism Survey has also included non-Jews as a group. The survey is administered by phone in Arabic and looks at issues that are both the same and different from those covered by the questionnaire for Jews. Among other things, the survey investigates aspects of identity via different cross-sections, including the question of what one’s primary identity is, from among several options: Arab, Israeli, Palestinian, or Arab Israeli. This year a very meaningful difference was detected on this question, compared with last year, mainly in the responses of Muslim Arabs (who constitute the decisive majority of non-Jews in Israel). The change consists primarily of a steep rise in the percentage of those who define their primary identity as “Israeli,” versus a substantial decline in the percentage of those who define themselves as “Arab,” and a sharp drop in the percentage of those who define themselves as “Palestinian.” In fact, in this year’s survey fewer than one in ten non-Jews in Israel said that their primary identity was “Palestinian,” while a quarter of the respondents (23%) defined themselves as “Israeli.” The percentage of respondents who self-defined as “Arab Israeli” remained virtually unchanged, such that, on the whole, nearly three out of four non-Jews in Israel defined themselves as “Israeli” or “Arab Israeli.”

The reasons behind this development are not clearly known. We need to wait for other surveys to see whether the change is a real one that will persist over the long term. It should be noted that other surveys, with unidentical questions, have already shown that the percentage of Arabs in Israel who self-identify as “Palestinian” is declining.[6] If this is indeed a development with staying power, there can be no doubt that a significant change has taken place in Arab Israeli society. A consultation with two statisticians (Professor Camil Fuchs and STATNET research institute founder Yosef Miklada) raised two hypotheses regarding the nature of the change which, as noted, will be verified or refuted only once additional surveys have been conducted.

One of these hypotheses is that the change reflects one of two technical issues. It is possible that sampling disparities caused a certain discrepancy between the surveys (though the differences between the findings are significant, making it hard to assume that a sampling gap was the sole factor). Another possible technical reason for the difference would be questionnaire structure. Because the question about the degree to which respondents feel like real Israelis appeared earlier in the questionnaire, it could be that this had a priming influence on the subsequent responses about identity.

The other, more important, hypothesis is that this year’s significant change was election-related: that it resulted from the discourse surrounding the elections; the substantial Arab election-day turnouts; and the notable presence of the party representing most Arab voters (the Joint List[7]) in the Israeli political arena, including coalition-building efforts and other parliamentary maneuvers. To this we may add the high visibility of Arab medical personnel during the coronavirus crisis. Much has been said and written this year about the 2019-2020 election period as a turning point in terms of Arab willingness to participate in the national political sphere.[8] It is likely that the JPPI survey reflects this change and the way in which it is also reshaping Arab Israeli consciousness.

Arab Israeli participation in Israel’s political system is, of course, a desirable trend. However, a number of obstacles remain that make it hard for the community’s political representation to join the Jewish-majority parties in full, or even in unstable (“outside support”) coalition structures. Israeli social researchers would obviously have a much easier time of it if all of the data from all public opinion polls pointed in the same direction, but that is not the case. Despite the sharp upturn, shown by the 2020 JPPI survey, in the share of Arabs attesting to an Israeli identity, and saying that they feel like “real Israelis” (two-thirds, if we include those who share that sentiment to a certain degree as well as those who fully embrace the attitude), one can discern stumbling blocks that hamper the minority’s complete integration in Jewish-majority society. This year, such signs are clearly visible in the non-Jewish responses to the question of whether a Jewish temple ever stood on the Temple Mount.

This is a highly fraught issue for both sides of the broader Israeli-Palestinian conflict, given the “denial by religious Muslims and many others of the historical link of Jews to the Temple Mount, the Western Wall, and the city [Jerusalem] in general, and on the Jewish side, non-recognition of the importance of Jerusalem to Muslims prior to the emergence of Zionism.”[9] Without touching on archeological findings or historical evidence, it is clear that a decisive majority of Jews in Israel (and elsewhere) believe that a Jewish temple stood on the Temple Mount. This belief transcends political camps and is not influenced by views on how to resolve the conflict. In the eyes of the Jews, the Temple is a historical fact, the denial of which (and such denial has increased in recent years[10]) can be understood only as an attempt to undercut the historical link between the Jewish people and the Land of Israel. This is true when the denial comes from the leaders of the Palestinian Authority and is undoubtedly also true when it surfaces in Arab Israeli public opinion polling.[11]

Half of non-Jewish Israelis, and a substantial majority of Muslim Israelis (59%) believe that no Jewish temple ever stood on the Temple Mount. Another third say they don’t know, that is, they are not persuaded that there was a Jewish temple but they do not deny it (this figure may hint at educational potential, at least regarding those who have yet to form an opinion). Among Christian and Druze survey respondents (they were few, meaning that the possibility of a sampling problem exists), half say they don’t know, while a quarter explicitly deny that there was ever a Jewish temple on the Temple Mount.

Israel-Diaspora Relations

The Pluralism Index is primarily concerned with Israeli society, but it also includes elements of obvious interest to Diaspora Jewry. For example, there are questions about attitudes toward streams of Judaism to which a large proportion of Diaspora Jews belong. There are also questions about Israeli positions on issues that link Diaspora Jewry to Israel. This year, in the Pluralism Index framework, we looked at Jewish-Israeli positions on two highly sensitive issues bearing on Israel-Diaspora relations. One was the question of who is a Jew. The other, which is of course closely related to the first question, was the Law of Return.

We mentioned the who-is-a-Jew question earlier, in the section on religion and state, noting that Israeli Jews take a conservative approach: nearly anyone who wishes to be considered Jewish needs either to have a Jewish parent, or to undergo conversion. Even so, the vast majority do not insist on the Orthodox format as the exclusive conversion channel. The Law of Return issue, which we addressed this year, adds perspective to our discussion with regard to Jews in Israel and abroad. Of course, such perspective may suffer from bias due to the coronavirus crisis, and its ramifications on public attitudes toward immigration generally. But in this instance, what emerges from the survey seems to be rooted in additional factors, including a recognition that, in recent years, most immigrants to Israel under the Law of Return have not been Jewish, and that the percentage of non-Jews immigrating under the Law of Return is rising. This fact has often come up in the public discourse, especially in the past few years (including the 2019-2020 election cycles).[12]

The large share of non-Jews among recent immigrants, which is fundamentally undisputed though different interpretations exist regarding the exact numbers, is already causing some leaders, especially within the religiously observant and Haredi sectors, to suggest that the time has come to change the Law of Return’s criteria. Chief Rabbi David Lau has proposed reassessing the Law, noting that “Israel needs to decide if it wants to be a welfare state for the Third World, bringing in everyone who has a connection with Judaism, or perhaps only those who are Jews.”[13] The Sephardi Chief Rabbi, Yitzhak Yosef, has endorsed this view, stating that “Those who bring in masses of non-Jews to Israel through [the grandchild] clause due to alien considerations are being unfair first and foremost toward those immigrants, and placing them at every stage of their lives before the untenable reality of living in a Jewish state. Amending the Law of Return is first and foremost in the interest of those immigrants.”[14]

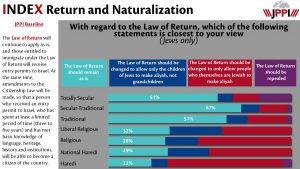

The Index data suggest that support for the Law of Return in its current form is eroding, and that less than half of the Jewish population approves of it unreservedly. That there is support for the idea that any Jew has the unconditional right to become an Israeli citizen is not really in question. Many past surveys have shown that “Israeli Jews of every kind – native-born and immigrant, young and old, secular and highly religious – agree that all Jews everywhere should have the right to make Aliyah, to move to Israel and receive immediate citizenship.”[15] But JPPI’s Pluralism Survey found that there are many Jews in Israel who feel that the Law of Return in its present formulation is too broad, and would like to circumscribe it. Some of them would be content with the elimination of the Law’s grandchild clause (which allows the grandchild of a Jew to immigrate to Israel), while others favor an additional eligibility restriction that would allow only those who are themselves Jews to immigrate and become citizens. The support for a Law of Return with stricter criteria is particularly evident among the religiously observant and Haredi populations. This fact takes on additional importance given that a large share of those who support eligibility restrictions are also those who advocate limiting conversion recognition to the Orthodox sphere. The religiously observant/Haredi sector thus supports restrictions on two fronts – both in terms of the number of paths enabling one to join the Jewish people, and in terms of the criteria that allow those interested in doing so, to immigrate to Israel.

Here it is worth noting that a stiffening of the Law of Return criteria, even should it spark controversy, would not necessarily be unacceptable to Diaspora Jewry as a whole. In a JPPI Structured Dialogue on the Jewish spectrum from a few years ago, it emerged that “the growing fluidity of identity in Jewish communities around the world is not leading all Jews to expect Israel relax its criteria for the Law of Return. In fact, the opposite may be true. The Dialogue participants tended to argue for further eligibility restrictions.” The Dialogue discussions revealed that a large share of participants from non-Israeli communities felt that “the current definition, which refers to the grandparents’ generation, is too broad.” In accordance with those findings, JPPI also explicitly recommended reassessing “the criteria of the Law of Return,” based on the rationale that, “in light of the cultural and demographic changes in the Jewish world, Israel may want to consider whether changes in those criteria are necessary.”[16] However, JPPI recommended that the Law of Return not be amended “without a frank and thoroughgoing process of consultation with Diaspora Jewry.”[17]

Technical Information

The Jewish People Policy Institute’s annual Pluralism Index is one of the products of JPPI’s broader Pluralism Project, which is supported by the William Davidson Foundation. The 2020 Pluralism Survey was conducted by Prof. Camil Fuchs of Tel Aviv University. The Survey included 604 respondents from Israel’s Jewish sector through an internet panel, and another 273 respondents from Israel’s non-Jewish sector via telephone. Respondents comprised a representative sample of the two populations surveyed. The Jewish sector survey was carried out by the Migdam Project, led by Dr. Ariel Ayalon. The sampling error is 4% at a significance level of 95%. The sampling error for the Arab survey, conducted by pollster Yosef Maklada, Director of the Statnet Research Institute, is 5.9%.

Footnotes

[1] See Shmuel Rosner, Maariv, www.maariv.co.il/journalists/Article-757989

[2] See the Hiddush surveys indicating that two-thirds of the Jewish public support the operation of partial or full public transportation on Shabbat: www.hiddush.org.il/Framework/Upload/ArticleImage_f014d6e2-bbc0-4249-a817-f4ec26549ddc_280.jpg

[3] See the Israel Democracy Index, in which the Chief Rabbinate regularly ranks at the bottom of the institutional scale. According to the 2017 Index, only 20% of Jews expressed trust in the Rabbinate: www.idi.org.il/articles/20082

[4] In this context it is worth mentioning a finding of the Jewish People Policy Institute’s #IsraeliJudaism project, namely that most young secular Israelis (under age 35) say they do not plan to marry via the Chief Rabbinate.

[5] For a detailed analysis of this issue see: Exploring the Jewish Spectrum in a Time of Fluid Identity, Shmuel Rosner, John Ruskay, the Jewish People Policy Institute, 2016.

[6] See the 2017 Shaharit survey, in which 14.6% defined their identity as Palestinian.

[7] It is worth noting that, along with the rise in Arab electoral support for the Joint List, the 2020 elections showed a drop in Arab votes for “Jewish” lists, such as Blue and White and Labor-Meretz.

[8] See: “The Spring’s Back in Their Steps: Arab Politics Following the Twenty-Second Knesset Elections,” Mohammad Darawshe, in Bayan, the Moshe Dayan Center.

[9] Quote from: Barriers to Peace in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, (Yaakov Bar-Siman-Tov, ed.), Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies, 2010. jerusaleminstitute.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/PUB_barriers_eng.pdf .

[10] See: From Jerusalem to Mecca and Back: the Islamic Consolidation of Jerusalem, Yitzhak Reiter, Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies, 2005.

[11] Less explicit signs of this denial can also be found in a Shaharit survey (2017) on the Jews’ historical relationship to Jerusalem and the Land of Israel.

[12] See “A Problematic Aliya: Only 53% of Immigrants to Israel in Recent Years are Jews,” Binyamin Lashkar, Mida, 2018.

[13] “Chief Rabbi Lau to Haaretz: Law of Return a Problem,” Yair Ettinger, Haaretz, April 14, 2014. www.haaretz.com/.premium-lau-law-of-return-a-problem-1.5245039

[14] “Rabbi Yosef Responds: Amending the Law of Return is First and Foremost in the Immigrants’ Interest,” Arik Bendar, Maariv, 2020.

[15] See: Israel’s Religiously Divided Society, Pew 2015. www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2016/03/israel_survey_overview.hebrew_final.pdf [English version (2016): www.pewforum.org/2016/03/08/israels-religiously-divided-society/]

[16] Exploring the Jewish Spectrum in a Time of Fluid Identity, Shmuel Rosner, John Ruskay, the Jewish People Policy Institute, 2016.

[17] 70 Years of Israel-Diaspora Relations: the Next Generation, Shmuel Rosner, John Ruskay, the Jewish People Policy Institute, 2018.