Editors: Noah Slepkov, Shmuel Rosner

Pollster: Professor Camil Fuchs

Main Findings

The survey on which the Jewish People Policy Institute’s Pluralism Index is based was conducted this year in the shadow of the coronavirus pandemic, and in the midst of an election season – Israel’s fourth in two years. The survey findings indicate that both have had an impact on Israeli cohesion. Below are a few of the main findings of this year’s Index, followed by a detailed discussion.

The COVID-19 Pandemic

- A substantial majority of Israelis view the behavior of the Haredi sector and, to a lesser degree, the Arab sector, as a blow to Israeli unity.

Cohesion and Partnership

- A slight majority of Jews and Arabs agree that “All Israeli citizens, Jews and Arabs, have a shared future.”

- A majority of Israeli Jews agree that “All Jews, in Israel and the Diaspora, have a shared future.”

A Jewish State

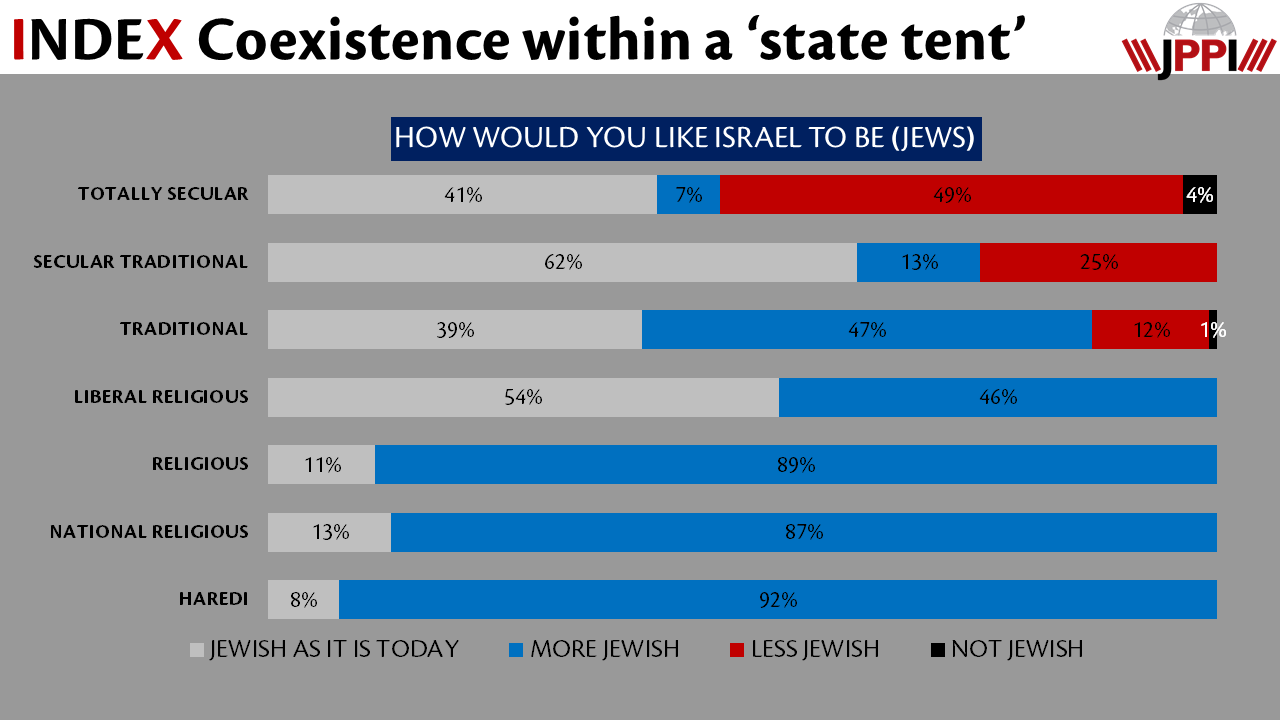

- Israel’s Jewish public is divided over whether Israel should be “less Jewish,” “more Jewish,” or “as it is today.”

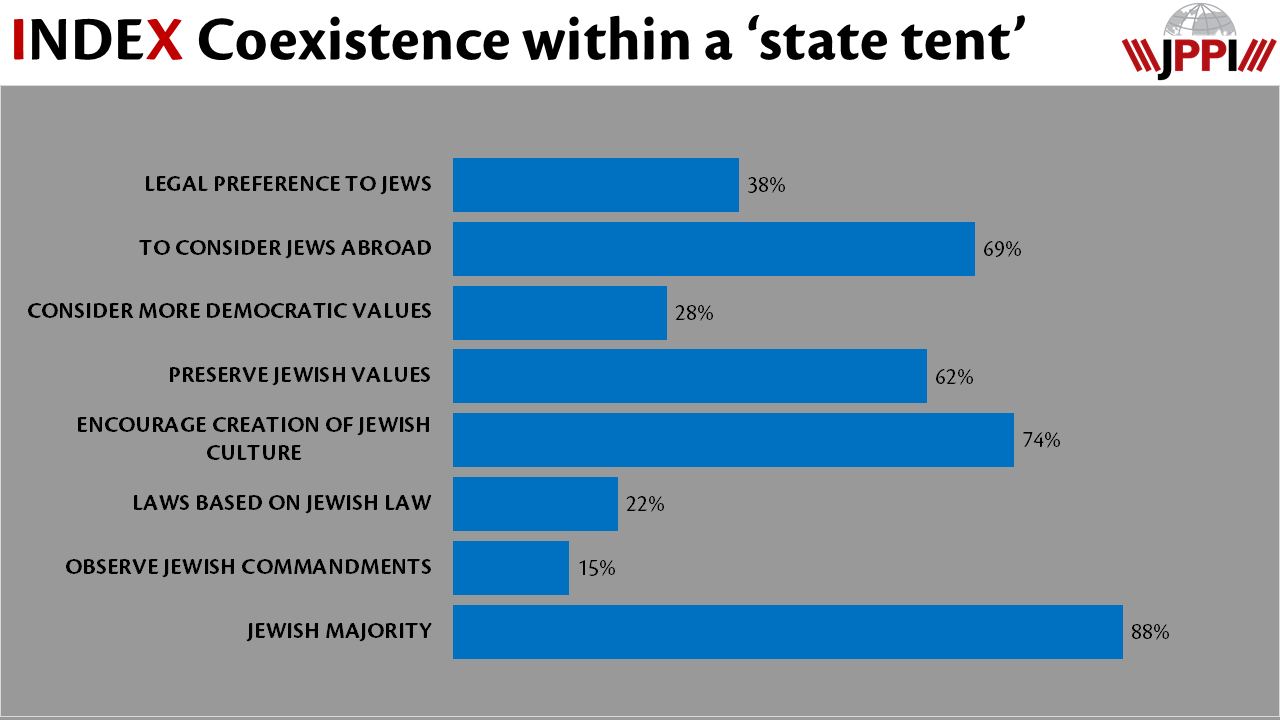

- There is a strong consensus among Jews that the Jewish state should have a Jewish majority and encourage Jewish creative activity.

- Only a tiny minority of Jews in Israel (1%) would prefer that Israel cease to be a Jewish state.

- Arabs would overwhelmingly prefer that Israel be a “state of all its citizens,” with no religious or national particularities.

A Democratic State

- A substantial majority of Arabs, and a majority of Jews, want Israel to be “more democratic.”

- A substantial majority of Arab Israelis do not regard Israel as a democracy.

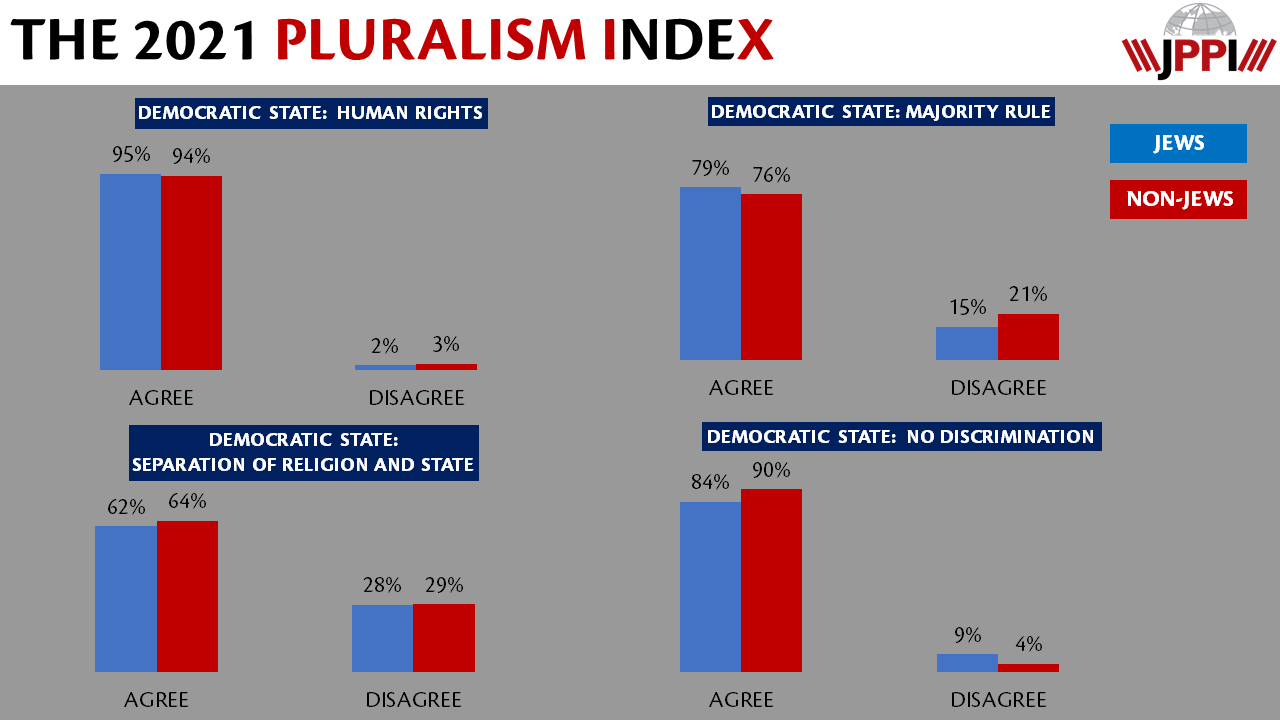

- There is a near-total consensus among Jews and Arabs that a democratic state should safeguard human rights and not discriminate against minorities.

Introduction

This is JPPI’s seventh annual Pluralism Index, and the sixth year that it is based, among other things, on a comprehensive opinion survey. As in past years, the survey included Jewish and non-Jewish respondents. In the case of the Jewish respondents, it drew on the large respondent base of JPPI’s comprehensive 2018 Israeli Judaism Survey. The Index comprises a list of set topics – issues whose development is assessed each year. We also examine various developments relative to a baseline by which the Institute strikes a balance between the positions and desires of different groups within Israeli society.[i] This year’s survey, like its predecessors, was conducted by Professor Camil Fuchs of Tel Aviv University. The Index project is edited by JPPI fellows Noah Slepkov and Shmuel Rosner. The Index baseline was written by JPPI fellow Brig. Gen. (Res.) Michael Herzog.

COVID-19 and the Elections

The Pluralism Index is not directly linked to immediate political developments, or to the health and economic crises in which Israel and the rest of the world were mired during the period of its compilation. Its purpose is to identify long-term trends, not to respond to short-term developments. However, crises often precipitate turning points whose effects persist even after the crises have passed. In this context, it is worth looking at some of the findings presented in the Index, especially those relating to groups that stood out during the pandemic.

There has been much discussion of the way in which the Haredi and the Arab Israeli sectors have responded to the governmental coronavirus guidelines. At different times during the crisis, these two groups drew attention for their inconsistent compliance with health system directives. The infection rate of both sectors was high relative to their population share. Each year, the Pluralism Index examines attitudes toward different population groups. Israel’s Haredi and Arab sectors both rank consistently low on the “contribution to the state” scale (this does not mean they don’t contribute, but rather that other Israelis perceive them as not contributing). Both groups rank low on the scale again this year.

This year’s Index also looked at the degree to which Israelis agree with two statements that reflect discomfort with the behavior of the two aforementioned sectors over the past year. “The behavior of the Haredim/the Arabs during the coronavirus pandemic undermined Israeli unity.” Both statements met with high levels of agreement among Jews, and moderate agreement among non-Jews. It should be noted, however, that both statements elicited very low agreement levels among the Haredim, but significant agreement among Arab Israelis. That is, the Haredim were inclined to assert that the behavior of the two sectors did not undermine civic unity, while the Arabs tended to say that the behavior of both sectors (including the Arab sector) did have a negative impact on civic unity.

Eight of every ten Jews (81%) respond the same in regard both to Arabs and Haredim. Of respondents, 13% maintained that only Haredim undermined civic unity and 5% claimed that only Arabs undermined unity. Among those who defined themselves as right-wing and non-Haredi, 9% stated that the Arabs alone undermine unity.

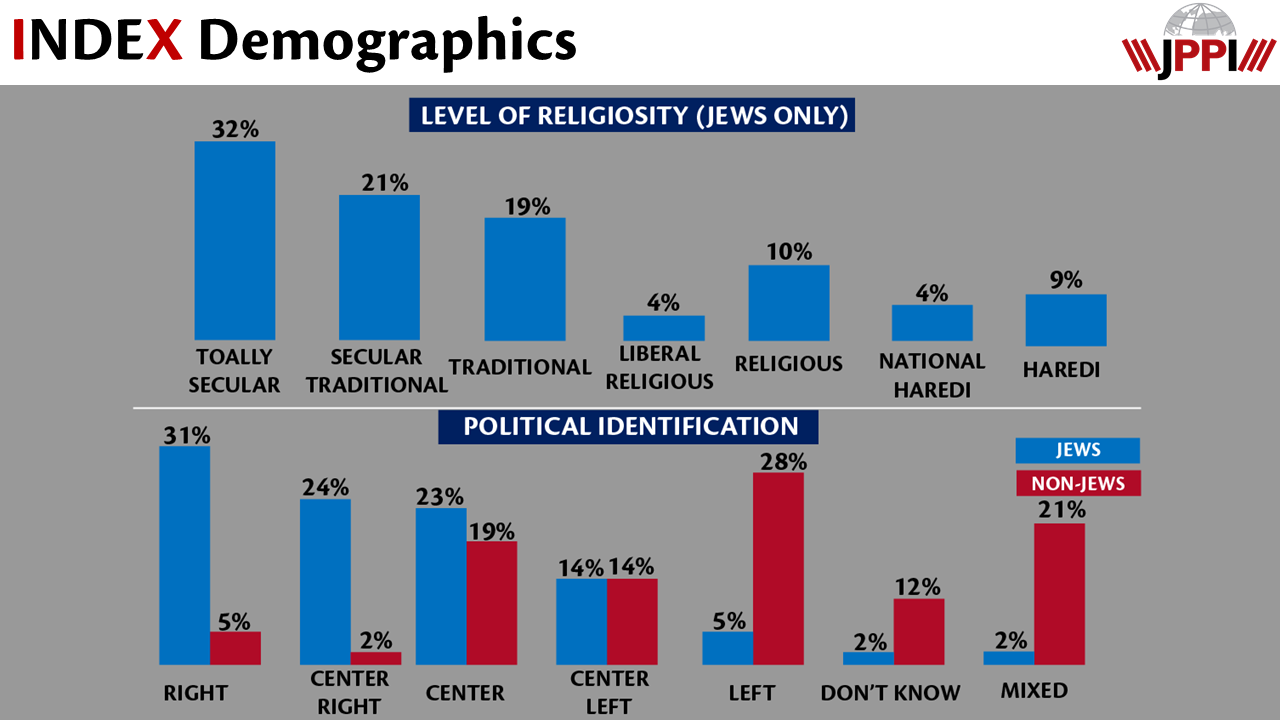

2021 witnessed Israel’s fourth election cycle in two years. The Index is not the place to expand on this issue. However, JPPI’s use of the same samples in its data assessments for the past four years makes it possible to identify long-term trends even in political contexts. Through comparative analysis of the responses of Israeli Jews to questions about self-definition, including responses in the political data field, we can identify rightward or leftward movements along the (5-step) scale, especially movements of one step up or down.

Thus, of the Israeli Jews who self-identified as “right” four years ago, 12% now identify as “center right” (while another 2% self-identify as “center”). Similarly, a third of those who self-identified as “left” four years ago (a small segment of the Israeli populace, amounting to 5 percent) now self-identify as “center left.” As far as we can tell from the available data, these moves do not bespeak a major change in political opinions, but rather a flexible attitude toward self-identification, one that is less concerned with rigid points of identification than with general comfort zones along the social-political spectrum. The political identification index puts half to two-thirds of Israeli Jews on the right-wing side of the spectrum (right and center right), a quarter at the center, and the rest on the left-wing side (mostly center left, with a small number self-identifying as “left”).

Areas of Partnership and Consensus

In this year’s Index, we focused on identifying partnership and consensus (or their absence) within three different circles: the general Jewish circle (Israel and the Diaspora), the general Israeli circle (Jews and non-Jews), and the Jewish Israeli circle (Jews in Israel). We delineated these circles via two frames of reference. One was that of people’s feelings and beliefs regarding other groups present in the given circle (e.g.: Do all Jews have a “shared future?”). The other was that of outlooks regarding the principles that shape the joint framework (e.g.: What does the concept of a “democratic state” entail?).

We identified areas of consensus and disagreement in all three circles, and different degrees to which respondents expressed a sense of partnership and their willingness to be in partnership. Naturally, as might have been expected, issues of major social and political controversy presented greater difficulty in terms of delineating circles of partnership. However, it should also be noted that a focus on controversy often obscures the existence of strong consensus on many other issues – consensus that could provide a foundation for defusing tensions, strengthening cohesion, and improving the joint quality of life of the groups in question.

The Supreme Court

To introduce our discussion of the areas of disagreement and consensus, we decided to mark out the dispute over the power and status of Israel’s “judicial system” as a disagreement directly linked to the past year’s political developments – the issue having also been of major consequence in this year’s elections. The image and powers of Israel’s Supreme Court are topics far beyond the scope of this paper. Nevertheless, they have become major points of contention along which lines are drawn between political groups. This has been particularly palpable in the past two years, due to several high-profile deliberations and rulings (the recent recognition of Reform conversions in Israel for purposes of Law of Return eligibility), the indictments filed against the Prime Minister, the intra-governmental disputes over the powers of the Attorney General, the appointment of a state attorney, and a few other issues pertaining to the judicial sphere – which in the public consciousness is connected with the status of the Court .

A serious dispute that has agitated Israeli governmental authorities for quite a few years now concerns the power the Court claimed, with the enactment of the Basic Laws of the 1990s, to invalidate Knesset legislation. This controversy, which has been reignited whenever the Court has overruled decisions on a wide range of issues, from how to handle illegal immigration to matters of religion and state, has long exceeded the bounds of polite discussion among jurists. It constitutes a major litmus test in the political arena, where elected officials have to commit to reforming the Court or to fighting it, to defending the Court or determining that it is dangerous, or is itself endangered – each faction according to its reasons and beliefs.

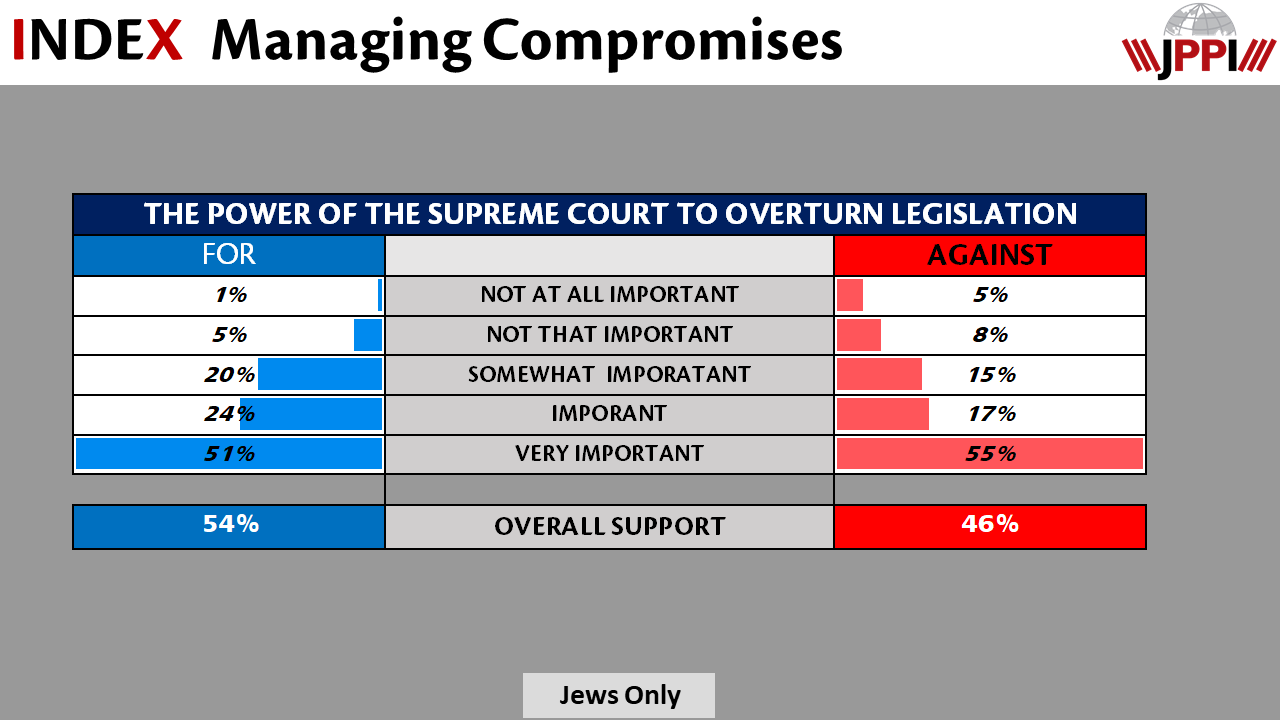

In Israel’s Arab sector, support for the Supreme Court power of judicial review is widespread (81%). Half of Arab Israelis attach “very great importance” to the issue. Most Arabs in Israel feel that it is important to maintain the existing power of legislative oversight in matters arising in the political sphere. In the Jewish sector the issue cuts across camps in a nearly equal manner. Slightly over half of Jewish Israelis (54%) support “the power of the Supreme Court to overturn laws passed by the Knesset,” while slightly less than half (46%) oppose this “power.” Among groups self-defining as “right” or “center right,” the number of those who oppose the Court’s authority exceeds the number of those who support it. This is also true for all religiously-observant groups, including the Haredim. In contrast, among those who self-define as left or center, and among the secular, there is overwhelming support for broad judicial powers (reaching 96% on the left).

The issue’s high-profile status, and its clear correspondence to the political affiliations of the Israeli populace, makes it hard for public debate to be conducted calmly, and amplifies its importance in the eyes of both “supporters” and “opponents.” Over half of both sides feel that the issue is “very important,” personally which could make it difficult for them to reach a compromise even if the fundamental disparity between the two camps isn’t as great as it sometimes appears.

Circle 1: Israel-Diaspora

The circle of Israel-Diaspora partnership is, paradoxically, at once the most comfortable and the most challenging.

Comfortable – because the Jews of Israel and of the Diaspora have no shared space in which practical conflict prevails on any subject. In recent years there has been extensive discussion of the “distancing” of Jews from each other, due to a variety of factors (a small number of them rooted in policy, but the majority arising from social or historical processes). And yet, even if there is a noticeable distancing, it is a phenomenon that develops in a slow process that is mostly hidden from view. Israeli and Diaspora Jews – certainly during a pandemic that hinders encounters and interactions – are managing their affairs in parallel. If a conflict arises between them, most do not become aware of it except by accident, and in such a way that its impact on everyday life is very limited.

Challenging – because the lack of conflict is itself a factor that breeds apathy and distancing. Because Jews in Israel and the Diaspora do not have a shared space, it is relatively easy for them to become indifferent to each other’s affairs. And more: it is becoming difficult for some of them to understand why interaction is necessary between people who aren’t partners in the building of a concrete enterprise. This year’s Pluralism Index findings show that the challenge has grown particularly acute among those Jews in Israel who are situated at the least-traditional pole of Jewish Israeli society. One may speculate that, for these Jews, the sense of a shared tradition and religion is not part of their worldview. There is a stronger feeling of distance with respect to those who don’t belong to the national-communal world in which they identify their major circle of commonality.

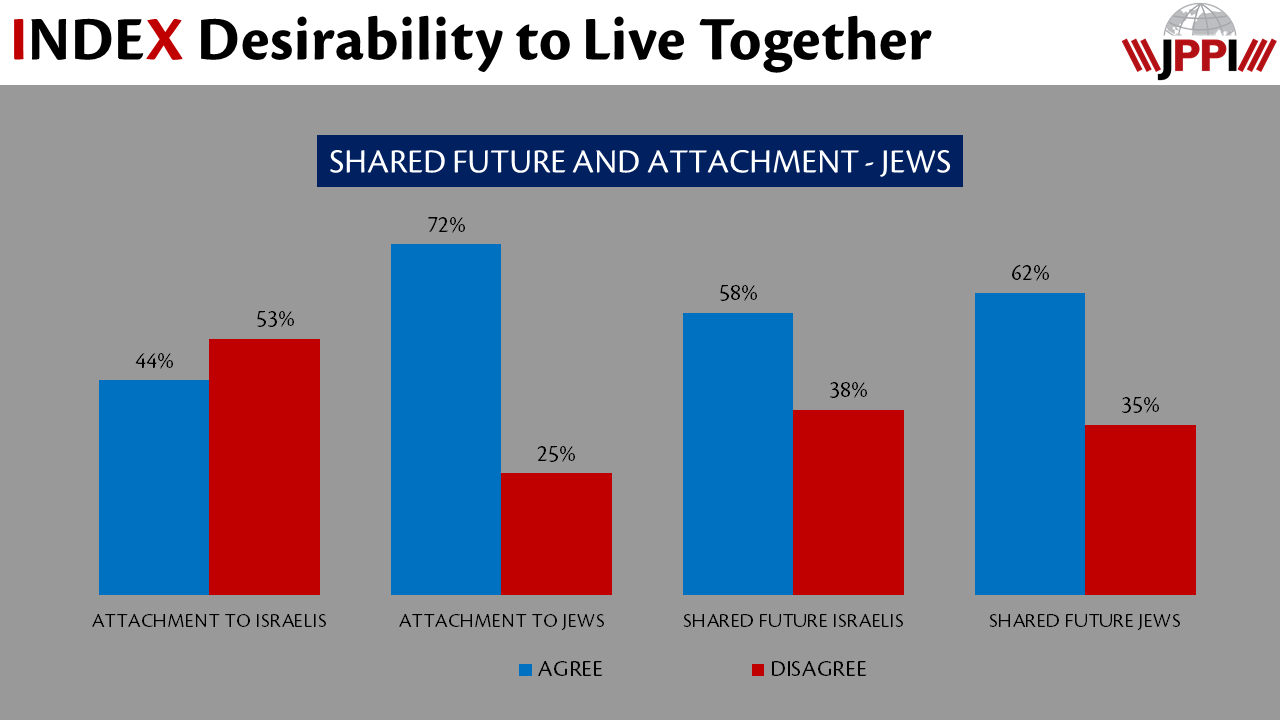

Accordingly, the data show agreement among two-thirds of Jewish Israelis that Israeli and Diaspora Jews have a shared future (62%). Nearly three out of every four Jewish Israelis feel an “attachment” to all Jews in Israel and abroad (72%). This gap, between a weaker sense of shared destiny and a stronger sense of attachment, is a conclusion that might reasonably be drawn from the differing life circumstances of Israeli and Diaspora Jews. The sense of closeness is an emotion that can be maintained even from a distance – in contrast to the sense of commonality that would seem to entail a more focused feeling of having a shared future.

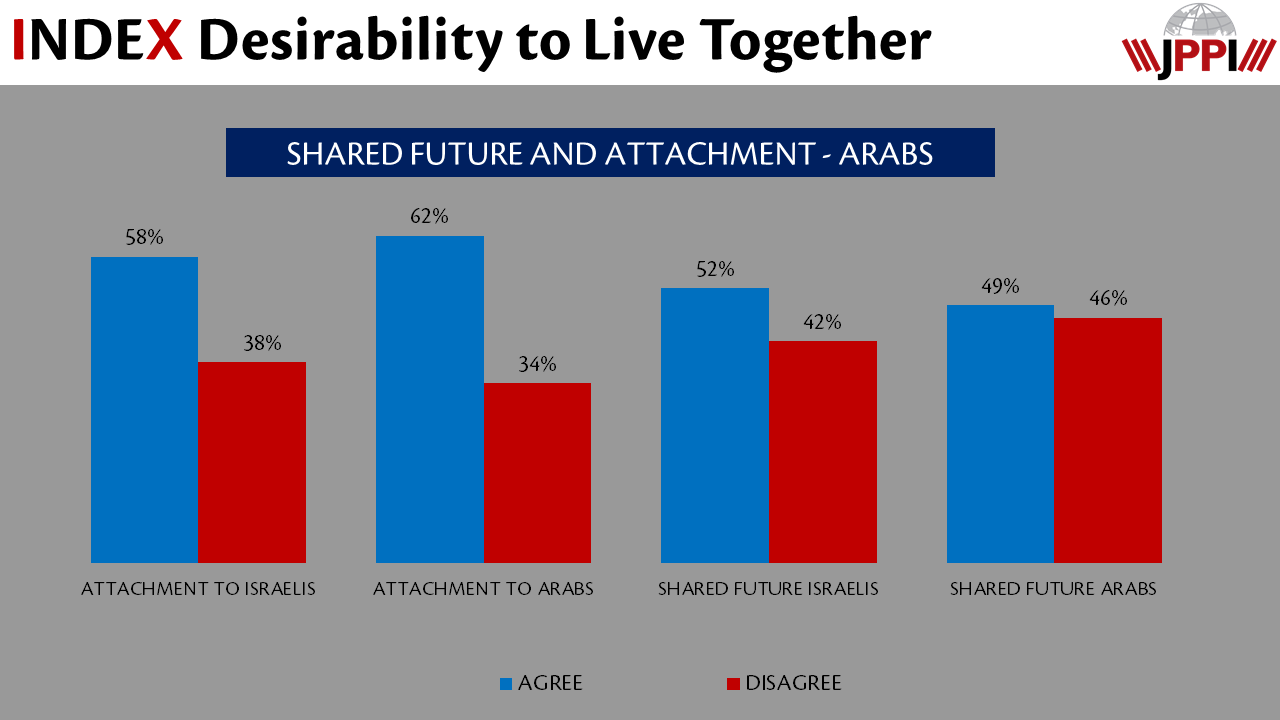

In this context, it is worth noting that many Arab Israelis also have a sense of a “shared future” with other Arabs, though the percentage is lower (49%) than the corresponding figure for Jewish Israelis vis-à-vis all Jews. Arab Israelis also exhibit a stronger sense of closeness to all Arabs than of having a shared future with them (62%).

Circle 2: Jews and non-Jews

The degree of partnership between Israeli Jews and non-Jews was a matter of public debate during the most recent election cycle. Longstanding conventions were shattered this time around, with the possibility of an Arab-party joining the coalition or providing it critical support while technically remaining in the opposition.

This new development was exemplified by the idea of the Joint List aligning with centrist and leftist parties to try to create an “obstructing bloc” to prevent the formation of a right-wing government under Benjamin Netanyahu. More importantly, it manifested in the Islamist party, Ra’am, backing several Knesset moves by the Prime Minister and the rightist bloc, and in Ra’am’s identification during the elections as a party that could potentially join either a right- or left-wing coalition.[2] Israeli public debate on the possibility of alignment between Jewish and Arab parties and voters gained momentum when the Prime Minister, a leader of the Israeli right for the past several decades, openly courted the Arab vote, visited Arab localities, and argued that the Arab electorate would do well to choose him.

Whether this constituted a serious effort or a tactical election-campaign move, its impact on the Israeli electorate, Jewish and Arab, cannot be overstated. The 2021 elections brought Arab parties and voters closer to full-partner status in the Israeli political game. This is also likely an outcome of processes noted in last year’s Index, where we reported a dramatic rise in the percentage of Arab Israelis who define their primary identity as “Israeli,” and a correspondingly steep drop in the percentage of those who identify as “Palestinian.”[3]

Most of the political debate in the political arena regarding Jewish-Arab relations revolved around the question of partnership and active Arab engagement in the political sphere. In the past few decades, there has been a gradual but very significant decline in Arab electoral support for “Jewish” parties, and a switch to near-exclusive support for parties identified with the Arab sector.[4] Accordingly, most of the discussion regarding this active partnership took place between political parties that directly target Arab voters. The sector’s main party, the Joint List, was challenged by Ra’am, which is identified with the southern branch of the Islamic Movement. The Arab parties have traditionally found themselves, whether involuntarily or by choice, outside of the coalition formation and stabilization negotiations. But Ra’am (and those Arab mayors who have expressed themselves on these issues) has been conducting itself as a party willing to use its support to safeguard its voters’ interests. There has been a particular emphasis on focused and thorough resolution of the problem of violence in the Arab sector, and on budget allocations for education, construction, and healthcare. This approach, should it become a long-term trend, would likely accustom the Israeli public to Jewish-Arab partnership on decisions relating to legislation, budgeting, domestic and foreign policy, and others.

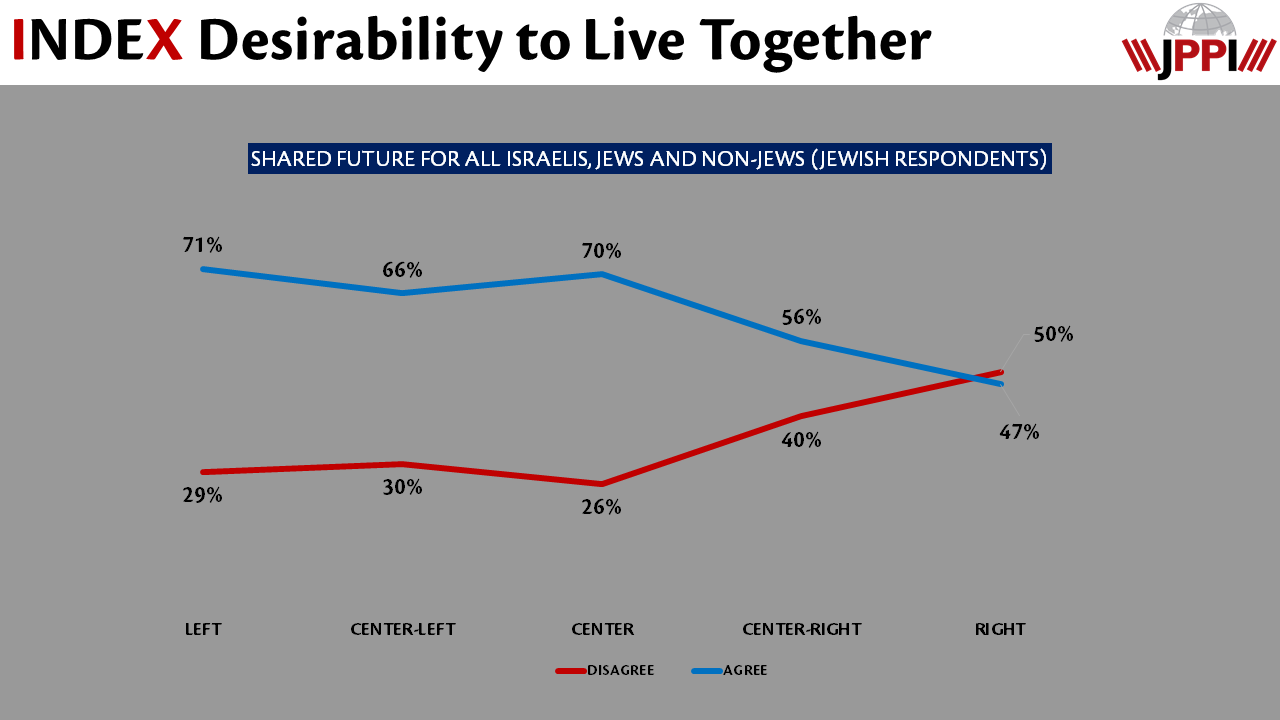

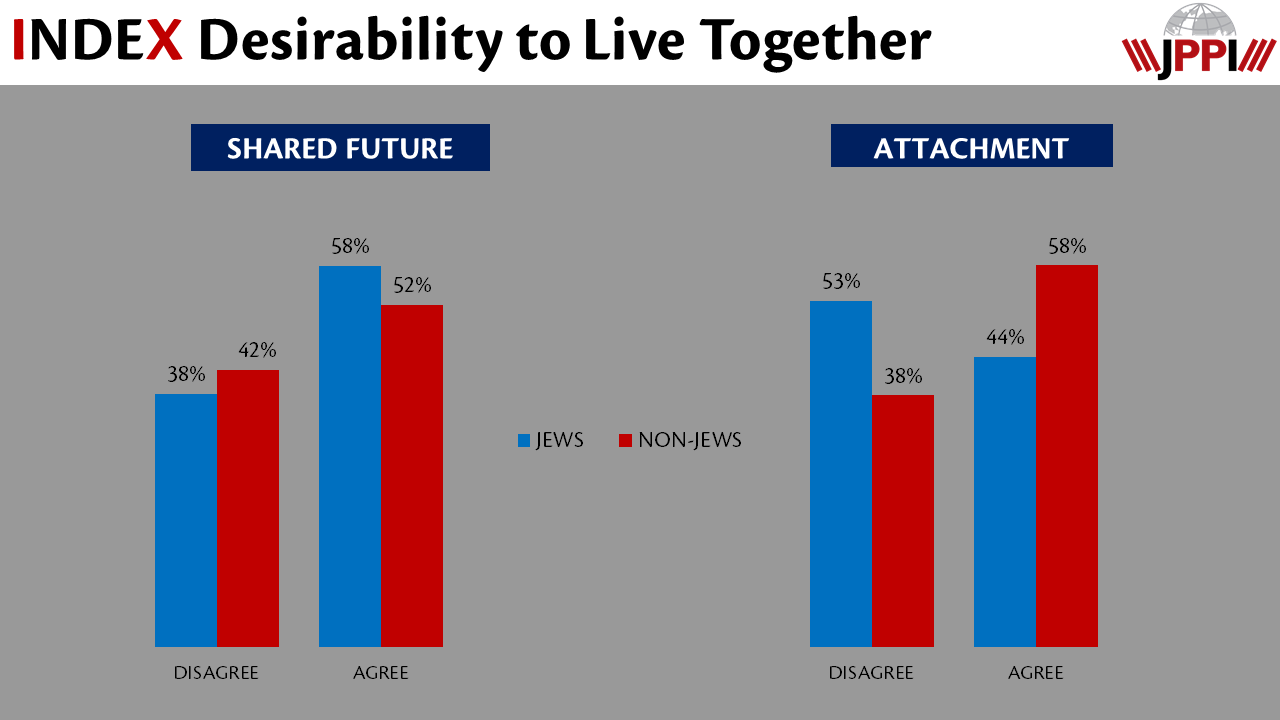

In JPPI’s 2021 survey, both Jews and non-Jews were asked whether they see a “shared future” for all Israelis, and whether they feel “close” to all Israelis. The questions were formulated to explicitly convey that they referred to both Jews and Arabs, and the (Jewish) responses obviously correspond to existing political camps, with the sense of partnership intensifying as the self-definitions move leftward. Among non-Jews, the Druze expressed a high level of agreement with the partnership statement.

With regard to the gaps between Jews in response to questions about “partnership” and “attachment,” we see an interesting pattern. While nearly half the respondents (49%) gave the same answer to both questions, a substantial number (25%) can be described as having “attachment hesitancy.” These are Jews whose attitude to partnership is more positive than to attachment– the difference is nearly always one level on the scale. For example: If they “greatly agree” with the claim that there is a “shared future,” they only “somewhat agree” that there is “attachment”; if they “somewhat agree” that there is a “shared future,” then they “somewhat disagree” that there is an “attachment” – and so on. It may be that the explanation for the lower shared level of attachment is on the one hand recognition by Jews that the Arabs are here to stay and that partnership is essential, along with a difficulty in turning such a partnership into attachment with an emotional dimension. Incidentally, among Arabs the phenomenon of attachment hesitancy” is not noticeable – 60% of them respond similarly to the question of partnership and attachment, and among the rest, there is no repeat pattern, but rather what appears to be a random combination of answers.

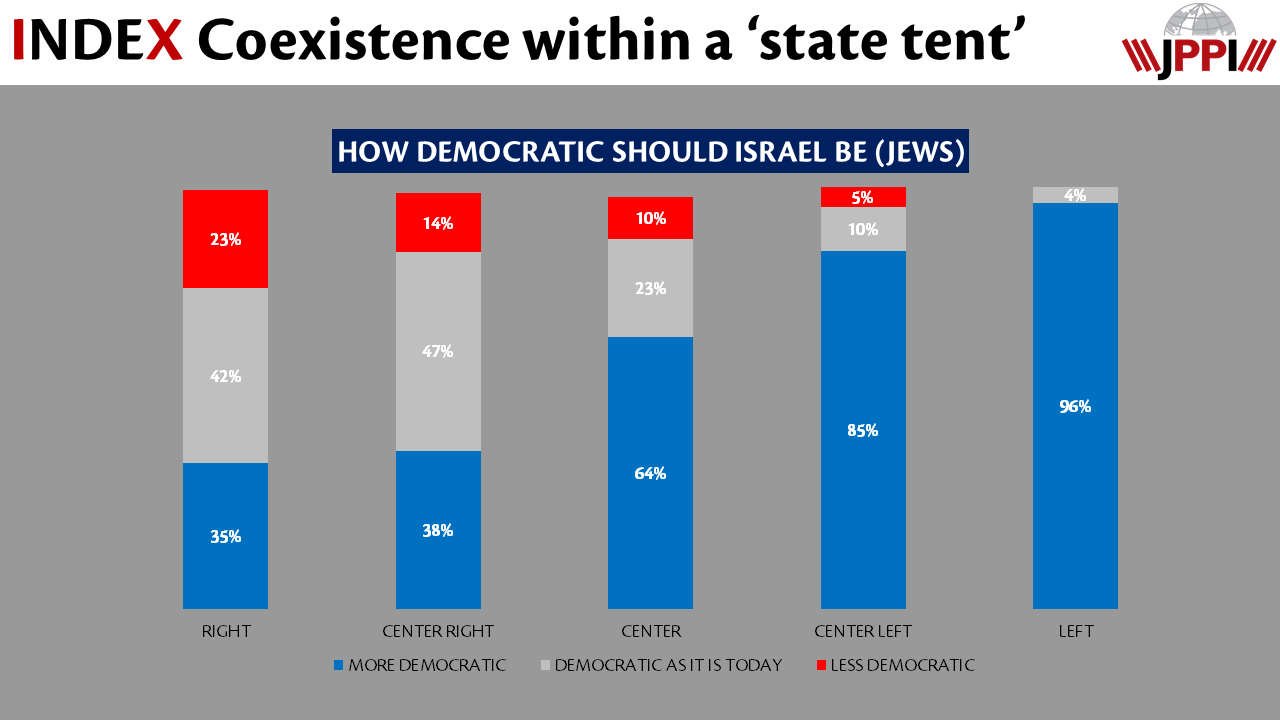

Jews-Arabs: A Democratic State

Jews and Arabs in Israel are deeply divided over whether Israel is a “democratic state,” i.e., whether it meets the standards of such a state. However, there is a significant consensus between the two groups about quite a few of the standards themselves, that is, the standards a state must uphold if it is to be considered democratic. The two sectors also share a desire for Israel to be no less democratic than it is today, and a feeling that it should ideally become more so. Most Jews (52%) and a substantial majority of Arabs (78%) say that Israel should be more democratic than it currently is. Only a tiny minority of Arabs, and a small minority of Jews (14%), feel that Israel should be “less democratic.” It should, however, be noted that the degree of democracy is directly related to political positions. Within the Israeli sector, the aspiration to be a “more democratic” country is a central component of the political agenda for those who self-define as center or left. In the two right-wing groups (right and center right), the largest share of respondents feel that Israel already strikes the correct democratic balance, while among the right itself the share who believe that Israel would do well to become less democratic (a quarter) is close to the share who think that Israel should be more democratic.

Many volumes have already been written on the question of what a democratic state is and what its characteristics are, and it is difficult to find an agreed decision on the rule. However, when the characteristics of a “democratic state” are presented to Israeli Jews and non-Jews, a broad consensus does emerge. Jews and non-Jews agree in high percentages about the principles of “majority rule,” “safeguarding human rights,” and “no discrimination.” A large majority of Jews and Arabs also agree that an independent judicial system is required of a democratic state. And it is interesting that even regarding the principle of separation of religion and state as a criterion of democracy – a principle about which internal disagreement is robust – we can see that Jews and Arabs are divided to a similar degree. A third of Muslim Arabs (34%) reject the separation of religion and state as a criterion of democracy, and a similar proportion of Jews (28%) share that view. The opposition intensifies as one moves along the religiosity scale from secular to traditional, and is highly visible among those who self-define as right-wing (a majority), and those situated along the Haredi and religious end of the spectrum.

Thus, Jews and Arabs do not agree about whether Israel currently deserves to be called democratic, but they do agree, though not in full, that Israel should become more democratic than it presently is. Moreover, they agree about whether most of the criteria presented constitute necessary conditions of democracy.

Nevertheless, these broad areas of consensus are no guarantee that major controversies over Israel’s “democratic” level can easily be resolved. This is because, as noted, a substantial proportion of Arabs (31%) feel that Israel is not a democratic state, with a slightly higher proportion (39%) saying that it is “not democratic enough.” At the same time, a slight majority of Jews (51%) do feel that Israel is a democratic state, with only a small minority (13%) averring that it is insufficiently democratic. Also, and more crucially, a large majority of Arab Israelis say that Israel, to be considered a democratic state, should be a “state of all its citizens,” an assertion that numerous studies have shown to be unacceptable to Jewish Israelis.

The statement presented to the non-Jewish survey respondents was: “A democratic state should be a ‘state of all its citizens’, that is, a state that does not emphasize the national or religious character of any specific group.” The share of non-Jews who agree with this statement is very high, 91%, with no significant differences between population groups, age groups, levels of religiosity, or religious affiliations. Many different conjectures can, of course, be raised about how the respondents understand the concept of “a state of all its citizens.” This concept, which has gained currency in Israeli public discourse since the 1990s, has taken on a variety of meanings. Among others, a demand to make Israel a “state of all its citizens” was presented at the so-called “Equality Conference,” the aim being to institute policy that would further the integration of non-Jewish citizens based on recognition of them as a national minority.

This demand raises a question about which there is no consensus, namely, whether the demand for “a state of all its citizens” contradicts the definition of Israel as a Jewish state. The High Court of Justice rejected the idea that the demand should be so understood. “It is our opinion that the definition of the State of Israel as a state of all its citizens does not preclude its existence as a Jewish state,” the justices wrote.[5] Experts who have studied the subject in depth have also found that “it is important to stress that the claim of a Jewish character of the state is usually not countered by claims to neutrality or to ‘a state of all its citizens,’ In the sense of privatizing all non-civic identities (as in France). Rather, it is countered by claims of different, possibly incompatible, identities and meanings (religious, national or a combination thereof). Many of the leaders of the Arab minority in Israel do not advocate a neutral, civic state; they aspire to reconstitute Israel as a bi-national or multicultural state.”[6]

Nevertheless, such appears to be the public’s understanding of this demand (and as it understood by many lawmakers, who expressed that understanding in the deliberations over the Basic Law: Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People). This view was explained by the Kohelet Policy Forum, which supported the law: “The law would affirm that all those who wish to see a bi-national state established here, or to revoke the Jewish national recognition and establish a state of all its citizens, are deluding themselves.”[7]

To conclude this section: The question of what Israel’s Arab citizens mean when they assert that a “state of all its citizens” is a condition of democracy, is one of the keys to determining whether there is an unbridgeable gap on this important issue between a substantial majority of Jewish Israelis and a substantial majority of Arab Israelis – or whether a fundamental consensus actually exists regarding the criteria for democracy, such that what appears to be a disagreement is in fact a simple misunderstanding about the meaning of the term.

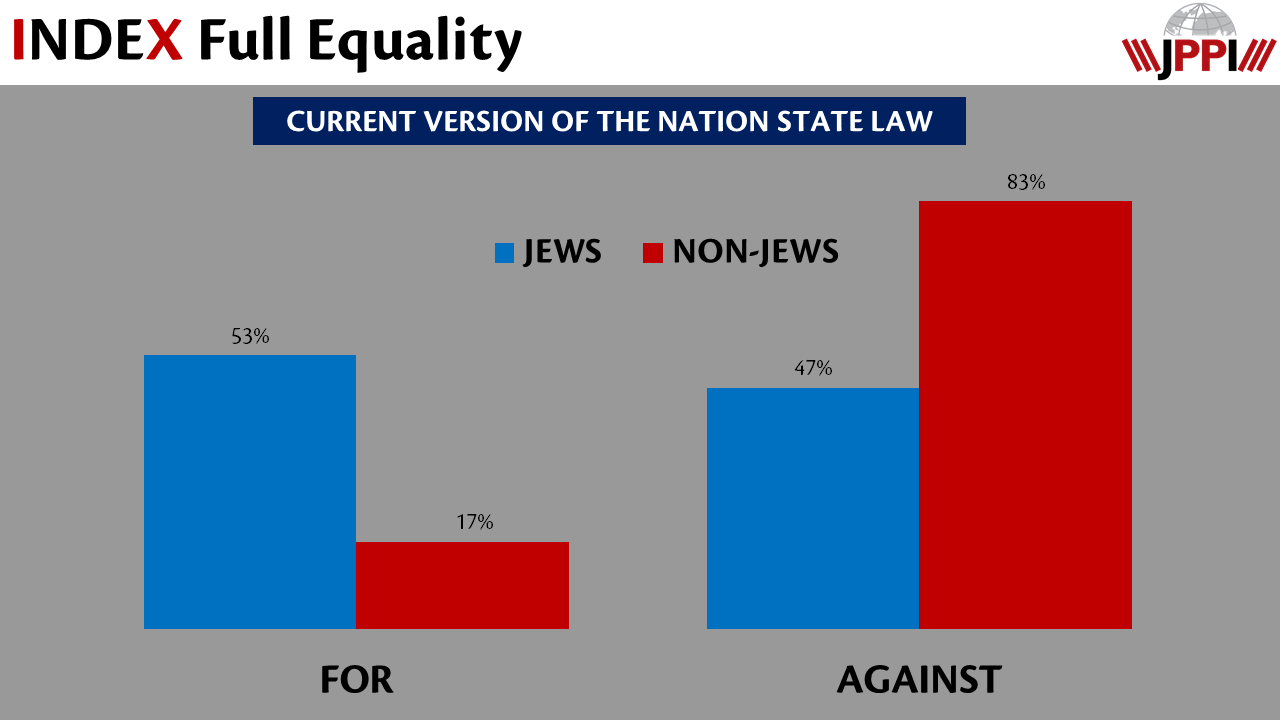

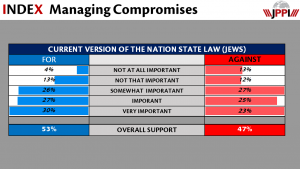

Jews-Arabs: the Nation-State Law

In the attempt to examine areas of agreement and disagreement, we also sought to clarify the degree of intensity Israelis express in relation to various issues. In other words, not only whether they are “for” or “against” a particular issue, but also how important it is to them. Clarification of this sort is a critical component of policy making, because often a group with a high intensity of opinion will be more significant in deciding an issue, even if holds a minority position. For example, one might have the impression that this is what happened in a debate on a compromise with regard to the additional plaza at the Western Wall several years ago, when the government preferred the wishes of a determined minority over those of a relatively indifferent majority.[8]

In this context, we sought to examine the 2018 Basic Law: Israel, the Nation State of the Jewish People.[9] This law, also mentioned in the previous section, states that “the State of Israel is the nation state of the Jewish people, in which it exercises its natural, cultural, religious, and historical right to self-determination.” It further states that “exercise of the right to national self-determination in the State of Israel is unique to the Jewish people.” This law largely eliminates both the possibility of defining Israel as a “state of all its citizens,” whether it is a definition that negates its nature as a Jewish state, or if it is a definition that allows parallel national realization to other groups. To a large extent, this was the purpose of its legislation, which was and still is a matter of fierce public debate.

Even when the law was enacted, it was clear that it was supported by Israel’s Jewish majority, and opposed by most of Israel’s Arab minority.[10] This is also evident in this year’s JPPI survey, which found that among Jews, support “for the existing version of the Nation State Law” stands at 53%, while among non-Jews, opposition to the existing version stands at 83%. The question focusing on the “existing version” was necessary because many argue that the Nation State Law could have been acceptable to them in other versions (in many cases, the addition of an equality clause to the law is an essential condition for supporting it).

As stated, in this year’s survey we wanted to examine not only public opinion, but also the level of importance opponents and supporters ascribe to the issue. The following segmentation of the positions of supporters and opponents, Jews and non-Jews, in regard to the Nation State Law shows that among Jews, the issue is more important for those who support the law, while among non-Jews, the issue is more important for those who oppose the law (almost 60% of opponents say that it is “very important” to them). The conclusion drawn from such data is that it will be difficult, in principle and practice, to reach an agreeable compromise on the wording of the law. The Jews who will oppose a change are both the majority, and also those who are more determined to support it. In contrast, non-Jews strongly oppose law’s wording to a great degree.

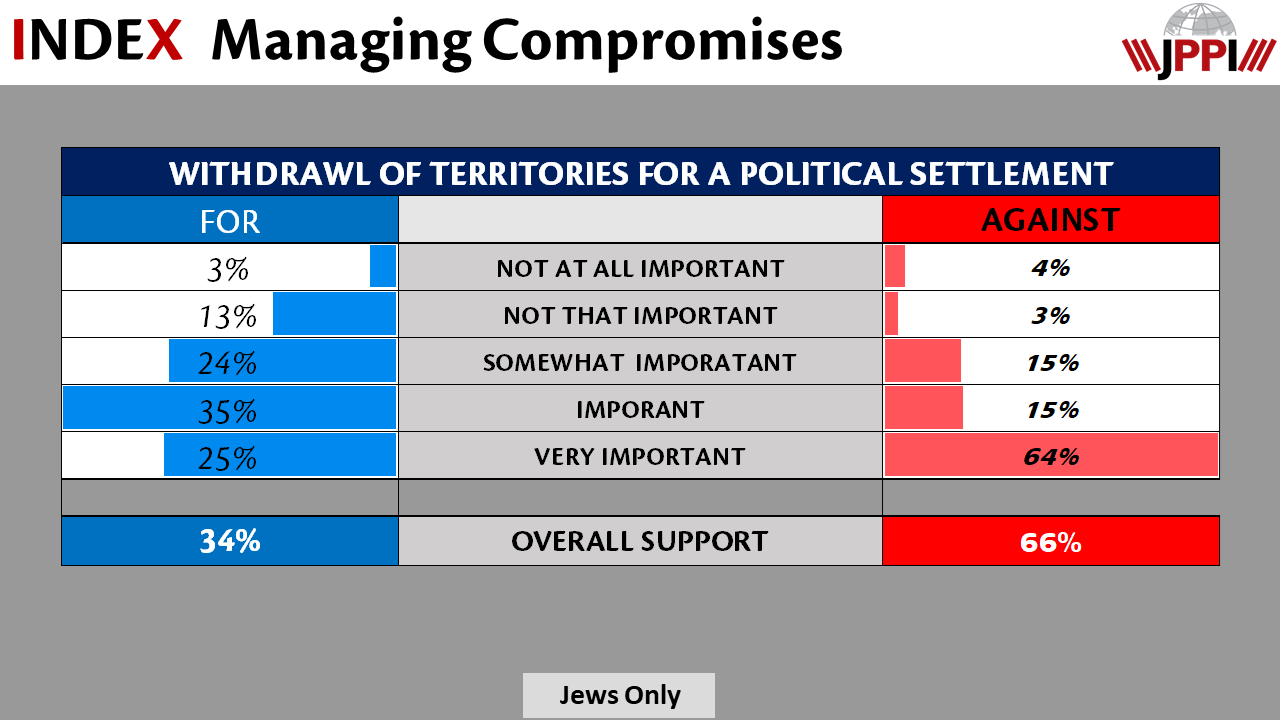

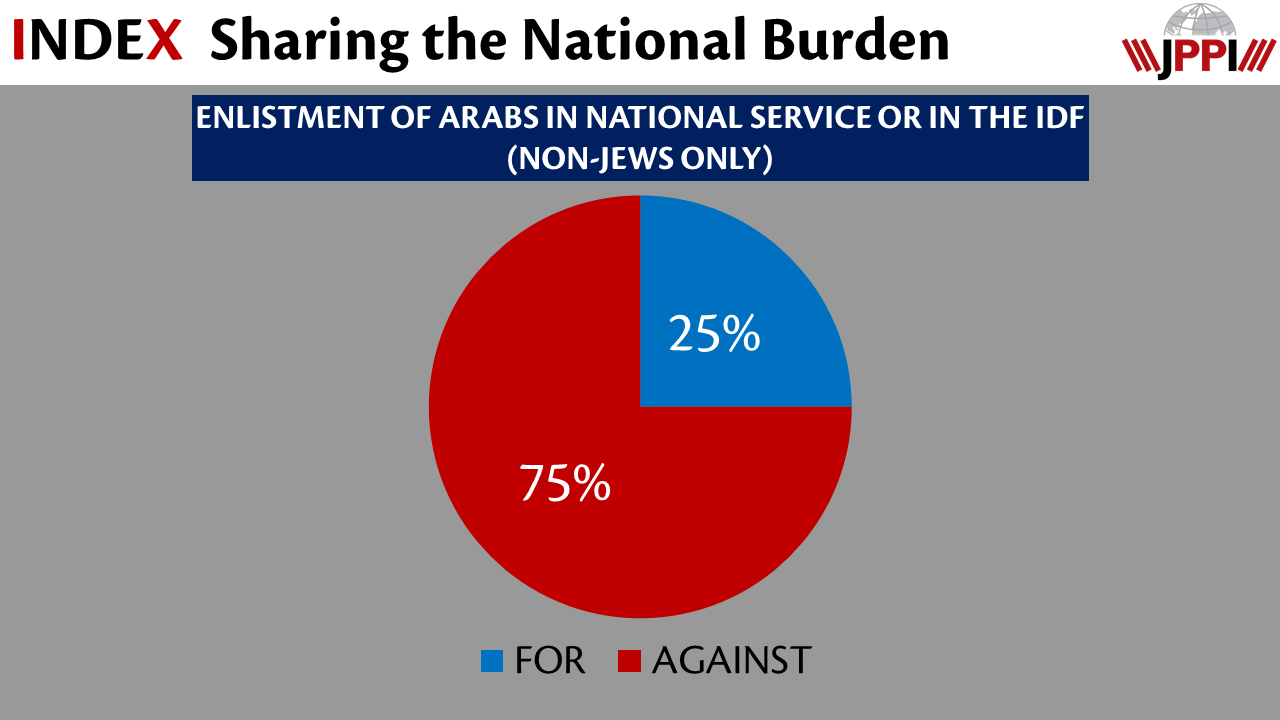

Another issue we examined is the construction and expansion of settlements in Judea and Samaria. Among non-Jews, it is clear that there is sweeping opposition to such settlement activity, and at a high intensity level. About two-thirds of non-Jewish respondents deemed it important or very important (50% of them said “very important”). A parallel examination of a slightly different question among the Jewish public (the wording of the questions differed at the recommendation of the pollsters in the two sectors) revealed that a large majority (66%) opposes “giving up the territories of Israel as part of a political settlement.” It further showed that the intensity of resistance to evacuating territories far exceeds the intensity of support for relinquishment of territories, as the following segmentation shows. Among those who oppose any evacuation, a significant two-thirds majority of the opponents attach great importance to the issue, while among those who support evacuation, it is clear that the issue is of much less importance. About 40% of supporters of evacuation rate it as “unimportant” or “somewhat important.”

As with the Nation State Law, data in regard to the public debate on the future of Judea and Samaria also show that at present the opponents of evacuation enjoy a significant advantage, both because they hold the majority position, and because the issue is of greater importance to them than for those who oppose it.

Circle 3: Israeli Jews

Most Israeli Jews believe Israel deserves the designation: “Jewish state.” Those who say it is either “too Jewish” and those who say it is “not Jewish Enough” are roughly equal in size with each composing one-fifth of the population. When Jews are asked how they would like Israel to be in the Jewish context, about 40% of them believe that Israel should remain “about as Jewish as it is today,” while the majority want Israel to be either “more Jewish” (37%) or “less Jewish” (23%). Only a tiny minority (1%) would prefer Israel to cease to be a Jewish state. And this figure is of course of great significance, because it makes it possible to identify a shared desire for Israel to be a Jewish state even if there is sharp disagreement over the desirable degree of its Jewishness.

As one might assume, it is clear from the data that those wanting the state to be “less Jewish” than it is today are largely at the secular pole of the religious spectrum, while the groups ranging from traditional to religious and Haredi want the state to be “more Jewish.” It is worth noting, however, that among secular Jews, only a minority desire a “less Jewish” state, whereas among most of the religious groups, a “more Jewish” state is an almost sweeping desire. Of course, such cohesion gaps can have a real impact on the translation of public sentiment into policy action. While some of the secular public may wonder whether they are expected to maintain the status quo or to try to bring about a fundamental change in the degree of Jewishness of the state, representatives of the traditional and religious public enthusiastically advocate shaping clear policy aimed at making the state “more Jewish” than it is today.

Of course, the way in which Jewishness is interpreted, whether one wants “more” of it or “less,” is of great practical significance. Therefore, the survey examined the conditions required, in the eyes of the Jews, for the state to be considered a Jewish state. Unlike the findings with regard to the conditions of a democratic state, in the case of the conditions of the Jewish state there are fewer across-the-board agreements. However, these can also be found. For example: a large majority of Jews agree that a condition for a Jewish state is a Jewish majority (88%). The few who oppose this condition are mostly left-wing and center-left people, about one-sixth of whom believe that a Jewish majority is not a necessary condition for a Jewish state.

There is relatively broad agreement against the condition that a Jewish state requires a majority of observant people. Four out of five Israeli Jews (78%) do not accept this condition. The Haredi group is the only one in which the majority feel that a condition for a “Jewish state” is a majority of observant people. This may explain why about one-fifth of Haredim believe that Israel today is not a Jewish state, and why most of them want it to be more Jewish. It may also make clear that, in the eyes of a majority of Haredim (51%), Israel will only be considered a sufficiently Jewish state when the majority of Jews become observant.

Similarly, a large majority of Israeli Jews (69%) do not believe that a condition for a Jewish state is a legal system “based on Halacha.” However, it is worth pointing out that this is a smaller majority than the overwhelming majority against the conditions of observance of the mitzvot. Still, there is a more significant group (22%) of Jews in Israel who believe that a condition for Jewish statehood is basing its law on Halacha. This is because the majority of Haredim (70%) also join the majorities of the “religious” (53%) and the “National Religious” (65%) on this issue. Let us be precise and clarify that the question did not refer to the possibility that Halacha be the law, but rather that the law be based on Halacha. This is not exactly the same thing, and it is important not to confuse the two.

There is consensus around the condition that a Jewish state should encourage Jewish cultural creation, for which there is agreement by a majority of the secular (57%), and large majorities all other Jewish sectors. With regard to the condition that a Jewish state must preserve the Jewish characteristics of the public space, significant gaps appear. The majority of the completely secular public – which constitutes close to a third of Israel’s Jews (32% in this year’s survey) – does not support it (37% support it), and slightly more than half of the somewhat traditional secularists support it (55%). Within the more traditional and religious groups there is much greater support for emphasizing Judaism in the public sphere, from around 73% among the traditional to almost complete support among the Haredim (96%).

Another significant controversy arises around whether “Jewish values must be more important than democratic values” as a condition for a Jewish state. In this case, only a minority of secular, traditional and religious liberals agree, whereas a majority of religious and Haredim agree. There are also divisions according to political orientation. Among those who self-identify as “right-wing,” a small majority gives preference to Jewish values (51%); in other political groups there is no majority for such a condition. In this context, however, it should be mentioned that the “right-wing” is the largest group of the five political groups in the survey (31%).

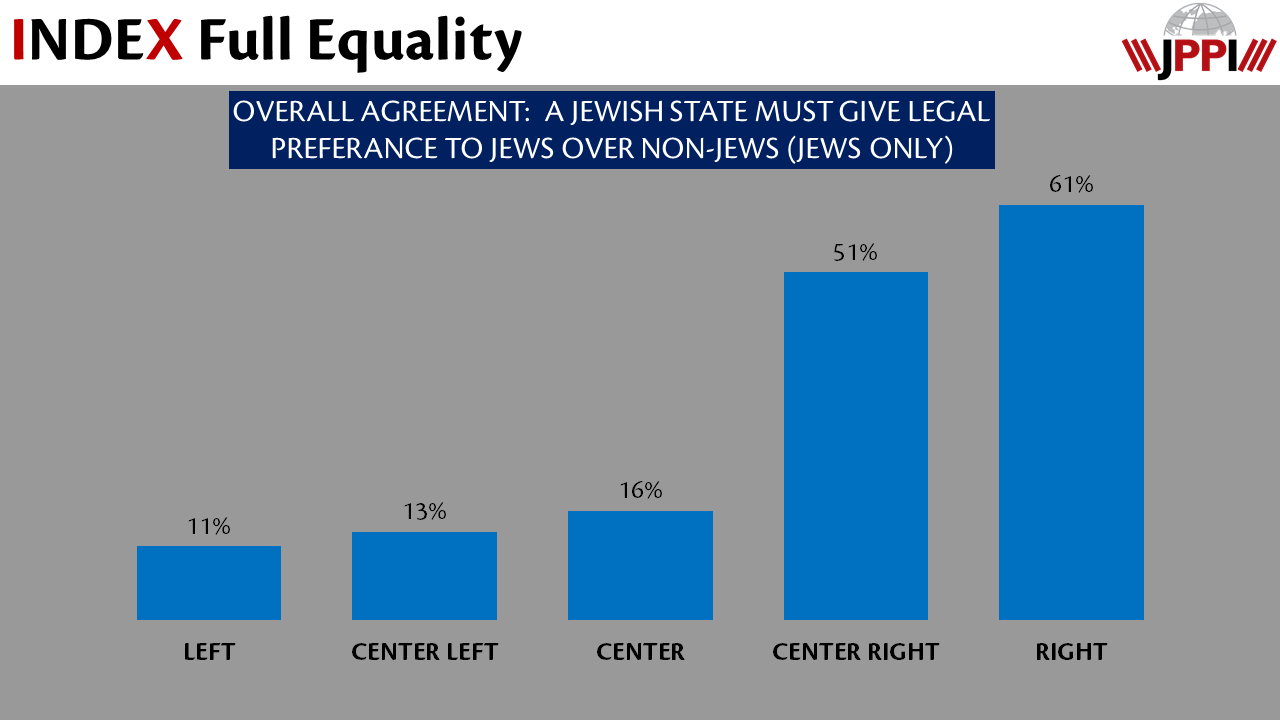

Yet another significant controversy arises around whether “a Jewish state must give legal preference to Jews over non-Jews.” In this case a significant majority of completely secular and somewhat traditional secular Jews oppose this proposition , but support rises as religiosity intensifies – from traditional to Haredi – (with the exception of the religious liberals). Among the Haredim, where support for this condition is the highest, it is about two-thirds (68%). Again, the division by political orientation paints a similar, although not identical, picture. In this case, support in the right-wing group is even more significant (61%), and there is support from a small majority even in the center-right group (51%). The gap between the political camps around this question is acute, with sweeping opposition to this condition from the center and the left (who are the minority, together making up 42% of Jews).

To sum up: there is almost complete agreement among Jews that Israel should be a “Jewish state.” In defining what this entails, points of relative agreement arise, such as the desirability of a Jewish majority and Jewish culture, as well as points of disagreement that relate to two aspects of the state’s Jewishness. One is the question of the extent to which “Jewishness” means “religiosity,” in the sense of religious observance, reliance on Halacha, and, to a lesser extent, aspects relating to the public sphere. The second is the aspects of the state’s Jewishness that have implications for the relationship between the Jewish majority and the non-Jewish minority. In this context, it is clear that a significant part of the Jewish population is interested in emphasizing Jewishness, even at the cost of violating other values, such as equality before the law, and “democracy.”

Shabbat and Marriage

Again, as part of the attempt to examine areas of agreement and disagreement, we also wanted to find out the degree of intensity that Israelis express in relation to various issues – something that is critically important in policy making. Thus, in questions about the Nation State Law, control of Judea and Samaria, Shabbat in the public sphere, the controversy over military conscription of the Haredim, the status of the court and more, we examined not only whether Jews in Israel support one position or another, but also the extent to which the issue is perceived as a priority. In general, it can be said that respondents tend to deem almost every issue “important,” and yet it is possible to distinguish between “importance” that is intensely felt and articulated, and a more detached “importance.”

An example we have already presented clearly shows that for those in support of keeping all the “territories of the Land of Israel,” the issue of transferring land as part of a political settlement is of much more importance than for those willing to consider evacuating areas certain areas. This can also be seen in the intra-Jewish context, that is, around issues that do not relate to Jewish-Arab relations, or to relations between Israel and its neighbors. For example: the issue of operating public transportation on Shabbat, a contentious issue in Israel for many years, is much more important to those who support it than to those who oppose it. As we also mentioned in last year’s Pluralism Index, in recent years (before the Covid epidemic, which disrupted all public transportation) it was possible to identify an uptick of the operation of public transportation on Saturdays, initiated and funded by municipalities across the country. This change was made possible when cities and municipal councils took advantage of a period in which the national political system was preoccupied with repeated elections as an opportunity to establish facts on the ground.

A significant majority of the public supports operating public transportation on Saturdays even though the official government position does not. As the data showed last year, support for unbridled public transportation on Shabbat is not great (about one-fifth of the Jewish public), but support for partial operation, whether by avoiding entering religious residential areas, or by enabling each municipality or local council to determine its own arrangements, rises to 75% among Jewish Israelis.

This finding has intensified according to the data collected this year: not only is the proportion of those who support public transportation on Shabbat higher, the importance of the issue is also greater in their eyes. This is probably due in large part to the fact that operating public transportation on Shabbat has become emblematic in the ongoing “religious coercion” debate and is therefore seen as a necessity by many who do not actually need it at all (last year’s data showed that car ownership does not significantly change one’s position on public transportation on Shabbat). The data also show that for most opponents of transportation on Shabbat the issue is rated between “unimportant” and “slightly important.” The question of why this matter has not yet been resolved is doubly valid. After all, on the one hand there is a small group of opponents for whom the issue is not very important, and on the other hand, a large group of supporters for whom the issue is important.

It is not easy to answer this question, but some suggestions can be made to untangle it.

First, the political structure of the coalition in Israel sometimes allows this type of anomaly to exist for a long time. At the same time, it must be said that in most cases anomalies eventually end in victory of the public over the political system. A clear example of this can be seen in the long struggle over opening cinemas on Shabbat, which eventually ended with a comprehensive victory for the supporters of opening.[11]

Second, what transportation supporters consider “important” and what their opponents consider “important” is not on the same scale. That is, the “not important” of the opponents is no less powerful, and perhaps more powerful than the “important” of the supporters. At least according to the level of energy invested in preventing transportation by opponents of the Knesset and the government, compared to the lower level of energy invested in preventing public transportation on Shabbat by representatives of the opponents in the Knesset and government, one might suspect that the scale of importance is indeed not the same. In other words – the same words are used (very important, not important), but the meaning is different.

Third, because the importance of the issue is largely symbolic, it is conceivable that it is expedient for both sides to maintain the conflict rather than resolving it because it serves as a tool with which to hit the other camp. Of course, this is not a deliberate, cynical move by those seeking to prevent a solution in order to sustain a conflict, but a natural dynamic of practical significance.

Either way, the conclusion of the data we have presented in the last two years with respect to public transportation on Saturdays is that this is an issue that could – and in our opinion should – be resolved by a compromise both sides could tolerate.

It is interesting to contrast this issue with another issue from the arena of religion and state – civil marriage.

Of course, the issue of marriage is far more complex than the issue of transportation, and concerns fundamental questions about the unity of the people, the ability of all Jews in Israel to enter into marriage, the human rights of those who are not allowed to marry because of some doubt regarding their Judaism, and more. Debate over marriage does not just pertain the type of marriage permitted (civil versus religious), but also to the institution responsible for registration and marriage. In the case of Jews, this is the Chief Rabbinate, whose poor image in the eyes of a significant portion of Jews (especially at the secular end of the spectrum, but not only) makes relevant discussion even more difficult (we discussed the image of the rabbinate briefly in last year’s report).

In addition to these complexities, and perhaps because of them, there is also a public sense of heightened importance, both for advocates of allowing civil marriage in Israel (a clear majority of the Jewish public, 66%), and for those who oppose it. A majority (around 60%) of those who oppose civil marriage characterize the issue as important or very important. Nearly 75% of Jews in the majority who support civil marriage define the issue as important to very important. From these data it may be concluded, or at least the concern may be raised, that resolution of the marriage issue through dialogue will be more difficult than resolution of public transportation on Shabbat issue. Such strong opposition and strong support is usually a recipe for intractable conflict, because both sides feel that the matter is too important to offer a concession.

However, it must be stated that unlike the issue of transportation on Shabbat, which is easy to understand, and its results noticeable (there is or is not a bus on my street), resolution of the marriage issue through dialogue, or even by forcing a new arrangement through a chance majority in the Knesset, requires expertise in complex issues of law, family, society, and Halacha. In other words: legislation or regulations that allow public transportation on Shabbat can be written and passed relatively easily when there is the required majority to do so, or given a fairly simple compromise struck through dialogue. On the other hand, a decision to move to another system of marriage and divorce in the State of Israel requires in-depth study of complex questions, where it is doubtful whether and to what extent the general public will want to delve beyond the headline of “there is / is not” civil marriage.

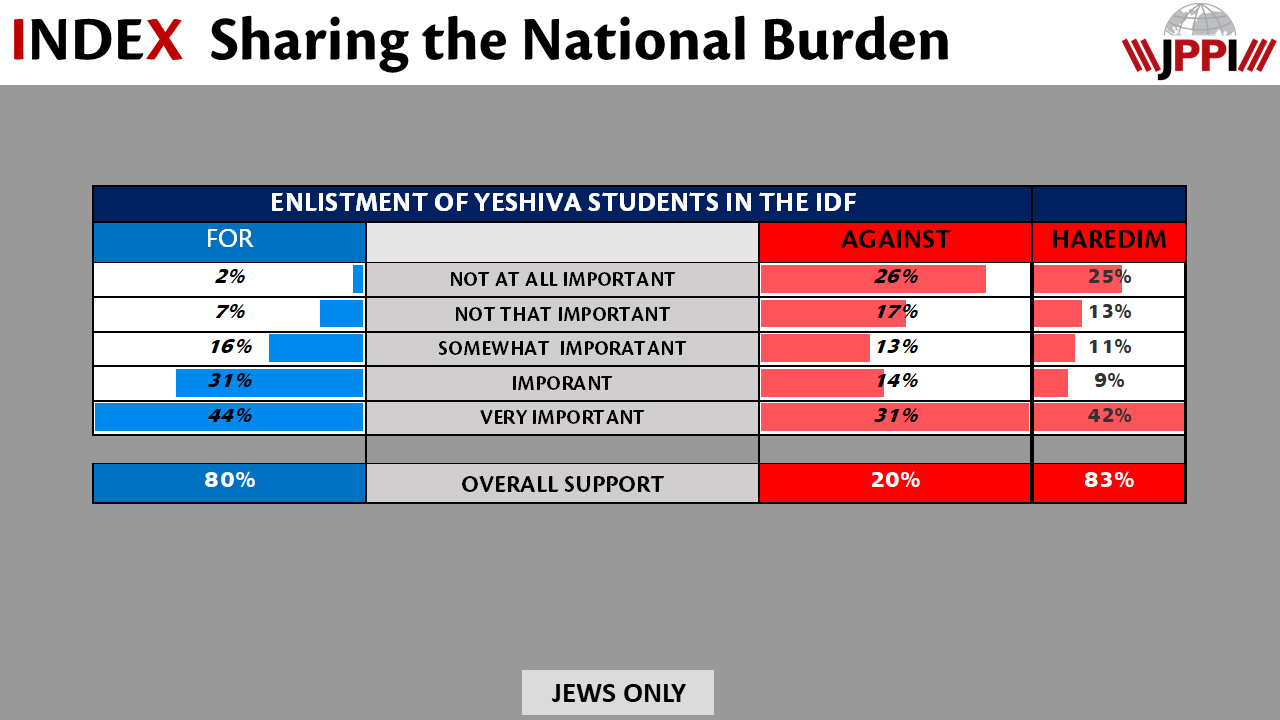

Enlistment of Yeshiva Students

An issue that is even more difficult to resolve, as both the political system and the courts have proved time and time again, is enlistment of yeshiva students into the IDF. Without delving into this matter, which is well known to every Israeli citizen, we will merely describe the findings that relate to it and some of the possible conclusions that derive from them.

About 80% of Israeli Jews support IDF enlistment of yeshiva students. In fact, the only group that opposes enlistment at a high rate (83%) is the one in which a significant proportion of its sons (and all its daughters) do not enlist. Among the National Religious group, there is still a small majority against enlistment of yeshiva students (57%), and in all the other groups support for enlistment is over 75% (and in most of them it is closer to 90%). As can be seen in the graph below, the issue is important for many Jews in Israel, at least according to their testimony. It is more important to those who are in favor of enlistment than to those who are against it, although when the opponents are separated from the Haredim (and it should be remembered that the percentage of opponents is very small) there is a reduction in the importance gap.

According to these indices, one might posit – as has been suggested above in the public transportation context – that this is a problem that will probably be resolved according to the will of the public. But the question of recruiting yeshiva students mainly concerns one sector, whose opposition to enlistment leads it, at least at this stage, to a rhetoric of practical and strident opposition, to the point where enlistment will require resources that are not justified by the benefit that can come from it.

Solutions to this situation have been widely proposed in the conceptual, political, and legal fields. Each has advantages and disadvantages, and most of them fall into one of three categories. The first is to relinquish the model of a “people’s army” because there is no way to realize it, and it therefore results in unacceptable inequality. The second is to levy sanctions against yeshiva students in order to dismantle the yeshiva framework as it has developed in recent decades, in the hope that such harm will lead Haredi society to a change of path, including recognition of the necessity of military service. The third is to adhere to the “people’s army” model, and exempt the Haredim from it, in parallel with an attempt to address other problems stemming from the current state of affairs (that is, participation in the labor force).

In this year’s survey, we did not examine the degree of agreement or opposition to these models, but it must be said that the data collected suggest that the time is not necessarily ripe for a discussion requiring a compromise on matters relating to the relationship between non-Haredi groups and the Haredim. This relationship is very charged, both politically, due to the recent frequency of national elections and the full affiliation of Haredi voters with one political camp, and socially, as a result of the conduct of Haredi groups and part of the Haredi leadership during the coronavirus pandemic. Without going into the question of whether the spotlight on Haredi conduct was justified or excessive, its effect is evident in the data. Surveys conducted earlier this year identified a high rate of anger and even hatred against the Haredim. Three out of four Israelis said they were “angry” with the Haredim because of their conduct as a group during the pandemic. More than a third of Israelis (37%) said they felt “hatred” for the Haredim because of their conduct during the pandemic. A minority (13%) said they “agree” with the statement “I feel hatred for the Haredim.” Another quarter of Israelis “somewhat agree” with this statement.[12]

In “contribution to Israeli Society” scale that appears every year in JPPI’s Pluralism Index, the Haredim have ranked low. Nearly half the Jews in Israel rate the contribution of the Haredim as negative (48%). Among the Arabs, almost eight out of ten (78%) rate the contribution of the Haredim as negative (it must be said that a significant majority of the Haredim, 66%, rate the contribution of the Arabs as negative).

Among respondents who participated in both JPPI’s 2020 and 2021 pluralism surveys, 62% did not change their opinion about the Haredim’s contribution to Israel, and the percentage of respondents who changed their opinion negatively is the same as the percentage of those who changed their opinion positively (20%). In response to the question of whether they agree that groups of Haredim acted irresponsibly during the pandemic, there was only a marginal impact on their view regarding the Haredim’s total contribution to the state. However, those who contended that the Haredim acted irresponsibly gave them, on average, a lower score for their contribution compared to last year, and those who believed that the Haredim did not act irresponsibly gave them on average a higher score than last year.[13]

And yet, the Haredim themselves rank their contribution as positive at a very high rate, higher than any other group examined this year (e.g., the Haredim value their contribution as higher than that of police officers, doctors, soldiers, and others). But this self-satisfaction does not convince other sectors. Most of them, as already mentioned, also believe at a high rate that “the conduct of the Haredim during the coronavirus pandemic has harmed the unity of the citizens of Israel.”

It is hard to see how, in such circumstances, it is possible to convince the many proponents of Haredi enlistment, who attach great importance to the issue, to accept a compromise that will exempt the Haredim from IDF service. Similarly, it is difficult to identify any interest among the Haredim in waiving the exemption. The March 2021 election results, which only highlighted the political power of the Haredi parties, and the assumption that no coalition will be possible without their support, have certainly not created an opportunity for a move whose long-term goal is to enforce enlistment, whether through economic sanctions or other forms of state coercion.

Summary

Results of the Knesset elections held in March 2021 – the fourth round in two years – provide a relevant and updated framework for summarizing the findings presented here. These elections ended without a definitive winner on either side of the political map regarding the main questions: Who will be the next prime minister? and How will the next coalition be assembled? Nevertheless, there were also a few signs that make it possible to identify what the public wants in regard to certain issues.[14] In effect, as with many of the issues that have been raised in this report, it is difficult to translate the public’s priorities into effective political action, and we end up yet again in another cycle of elections (at the time of this writing, it appears that there is a distinct possibility of a fifth round of elections in the Fall of 2021).

The difficulty in translating the public agenda and priorities into political action is evident in almost every section of this report.

In the first circle, along with the feeling of a shared destiny between Israeli Jews and Diaspora Jews, there is a tendency in the political system to ignore different decisions (as in the case of the Kotel arrangement) that reflect this feeling in favor of political considerations. This highlights a paradox already seen in the past. The feeling of closeness to Diaspora Jewry is actually stronger among Israelis who voted for the ruling coalition over the past decade. However, it is these same Israelis who tend to be less supportive of measures that have real potential to bring certain groups of Diaspora Jews, who feel distanced from Israel, closer. The population groups that feel close to Diaspora Jews are also those whose positions on many issues – some related to religious and cultural pluralism, others related to political matters (peace and security) – make it difficult to bring the two groups closer together.

In the second circle, which concerns relations between Jews and non-Jews in Israel, we can discern a recognition among most Israelis that the two groups have a shared future (even if this recognition has not yet translated into a feeling of emotional closeness). This recognition was also evident in the recent elections, where an interesting new element was the controversy among Israeli Arabs regarding the scope of cooperation between the Arab political factions and the majority Jewish factions. Even in the parties that represent Jews, including those with groups with major ideological reservations about Israeli Arab views on national issues, there is a discernible degree of potential acceptance of Israeli Arab cooperation in the political arena in a way that has not been seen in the past.

Along with this positive development, we should note that there are still fundamental issues that make cooperation between Jews and non-Jews in Israel difficult. Many Arab representatives claim that Israel takes an exclusionary stance in legislation and resource allocation (passage of the controversial Nation-State Basic Law is cited as a clear illustration of this state of affairs). On the other hand, many Jews will find it difficult to ignore the fact that along with the clear willingness to cooperate in recent years, there are still prevalent Arab public attitudes on national issues the Jewish majority finds hard to accept. This is both with regard to the state’s Jewishness and other general political issues (the opposition by key Arab representatives to the Abraham Accords highlight the fault line), as well as the Jews’ main cultural narrative, as illustrated in the past year in the question related to the Jews’ link to the Temple Mount (only one in five Israeli Arabs in Israel recognize the fact that there was a Jewish temple on the Temple Mount).

The tension created between the growing willingness to cooperate and both groups’ attitudes on major issues will certainly contribute to the difficulty of turning the positive signs cited in this report into specific governmental political action. However, the very fact that Israel is finding it difficult to extricate itself from the political stalemate and must engage in yet further elections in an attempt to stabilize the government, points to the possibility of breaking down the political and psychological barriers between Jews and Arabs. Cooperation on a practical level just might, in the future, lead to diminishing the remaining ideological gaps.

The third circle, which relates to intra-Jewish controversy surrounding the very image of the state, highlights even more than the others the difficulty in turning the clear and unequivocal priorities of a substantial majority of the public into practical policy. (This difficulty, to a certain degree, also contributes to political stagnation by leading to secondary conflicts that thwart cooperation between groups otherwise in accord on most issues). And so, despite overwhelming Jewish public support for rescinding the current arrangement that exempts Haredim from military service, the political system has failed to find any solution under the pressure of one group’s uncompromising insistence on continuing this arrangement.

Additionally, although there is broad consensus among the Jewish public about the need to permit civil marriage in Israel, the political system, again and again, privileges the minority position and does not attempt to find a solution for this issue. And, even with regard to a seemingly simple matter of public transportation on Shabbat, which according to our findings should not present a significant obstacle in reaching an understanding, the government refrains from pursuing any resolution. As with other issues in the past (for instance, businesses opening on Shabbat, which is ostensibly prohibited but in fact is fairly widespread), it appears as if the government, in hindsight, comes to terms with steps already taken “in the field” instead of taking an orderly policy approach.

All of these examples clearly raise the possibility that the main obstacle to resolving tensions in Israeli society does not derive (in many cases) from profound gaps between groups, but rather from the structure – and even more so the culture – of Israel’s political arena. This arena, which is supposed to be a space for providing practical solutions for complex issues, often appears as a battlefield in which every compromise is interpreted as a defeat, and every issue is decided according to group and faction priorities, and not according to the wishes of the majority of the Israeli public.

Technical data

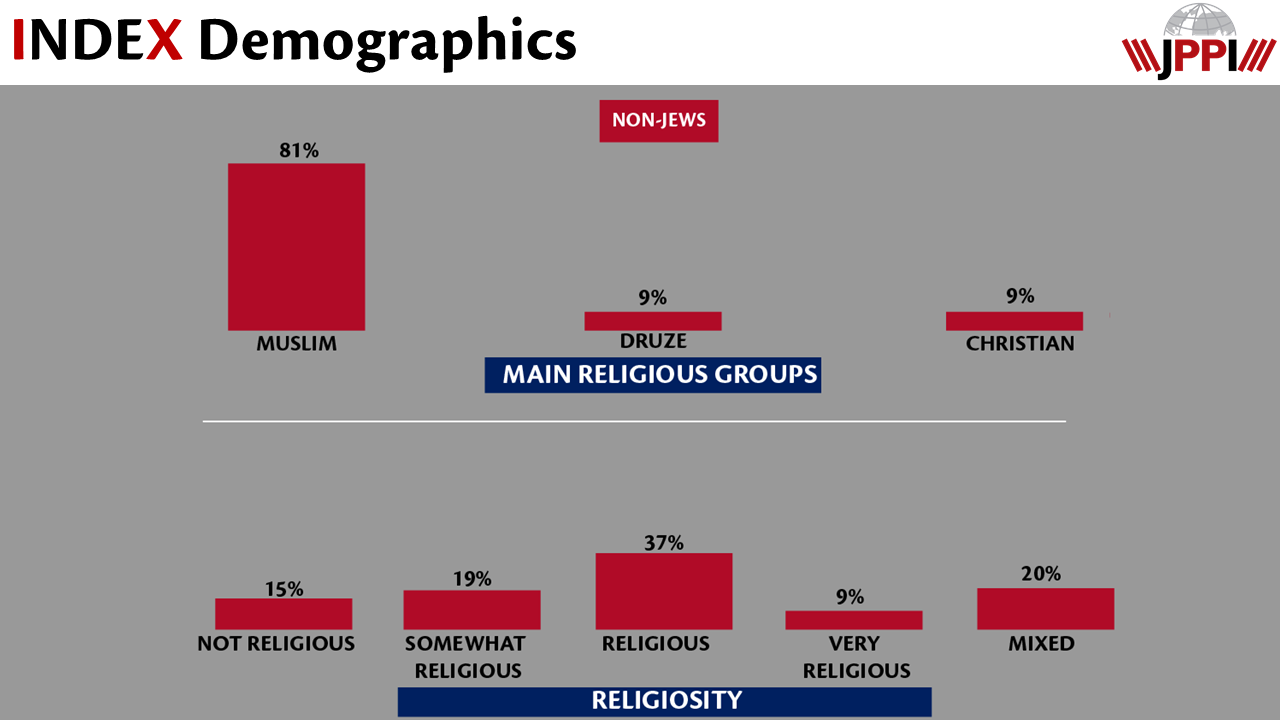

JPPI’s Pluralism Index Survey is one of the products of the Pluralism Project initiated by the William Davidson Foundation. The 2021 survey was conducted by Prof. Camil Fuchs of Tel Aviv University. It included 603 respondents in the Jewish sector, via an online panel, and another 203 respondents in the non-Jewish sector through a combined online and telephone survey. The Jewish sector’s religiosity levels in the 2021 and 2019 surveys are based on those of the 2017 survey respondents. The respondents constitute a representative sample of the two populations surveyed. The survey in the Jewish sector was conducted by the Midgam Project, headed by Dr. Ariel Ayalon. Sampling error 4% at a significance level of 95%. In the non-Jewish sector, the survey was conducted by Afkar. Sampling error 9.7%.

[1] The baseline appears in full at the end of the data presentation.

[2] See: “After Decades Have Passed: Arab Society Has a Right and a Left,” Muhammad Majedele, Globes, March 2021.

[3] See: Pluralism Index 2020, Jewish People Policy Institute. jppi.org.il/en/article/index2020/#.YFxA2q8zaUk

[4] See: Arab Voter Turnout in the Knesset Elections, Policy Study 148, Dr. Arik Rudnitsky, Israel Democracy Institute, 2020.

[5] CAA 231696 Meron Izikson v. the Registrar of Political Parties, 1996. cjdl.org.il/files/izikson.pdf

[6] Constitutional Anchoring of Israel’s Vision, Ruth Gavison, p. 20. media.wix.com/ugd/ebbe78_44305ffd44d34f77a40db8623be25a89.pdf

[7] Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Nation-State Law but Were Afraid to Ask, Kohelet Forum website, kohelet.org.il/publication/מה-שרציתם-לדעת-על-חוק-הלאום-ולא-העזתם-לש

[8] See: Putting the Kotel Decision in Context, Shmuel Rosner, Dan Feferman, JPPI, 2017. jppi.org.il/en/article/english-putting-the-kotel-decision-in-context/#.YFMWEi0Rrq0

[9] fs.knesset.gov.il/20/law/20_lsr_504220.pdf

[10] See, for example, the Democracy Institute survey www.peaceindex.org/files/Peace_Index_Data_July_2018-Heb(1).pdf

[11]For more information, see: #Israeli Judaism, Portrait of a Cultural Revolution, Shmuel Rosner, Camil Fuchs, published by the Jewish People Policy Institute and Dvir, 2018. Pages 51, 118.

[12] Data from theMadad and Kan News. Does anger against the Haredim border on anti-Semitism?, theMadad, February 17, 2021.

[13] With respect to the Arabs, it appears that the pandemic is having a greater impact on general contribution to society opinion. About half the respondents changed their opinion about the Arabs’ contribution to Israel during the previous year, and nearly a third ranked the contribution more negatively. Those who felt the Arabs acted irresponsibly during the pandemic changed their general view for the worse with respect to the Arabs’ contribution. Those who did not agree with the statement that the Arabs acted irresponsibly changed their general opinion regarding the Arabs’ contribution for the better only slightly.

[14] See: The Elections in Israel – Initial Lessons, Shmuel Rosner, Jewish People Policy Institute, March 25, 2021 jppi.org.il/en/article