Israelis on the 2026 Elections, Trust in Leadership, Values, Israel’s Strength, and Optimism about the Future.

Main Finding

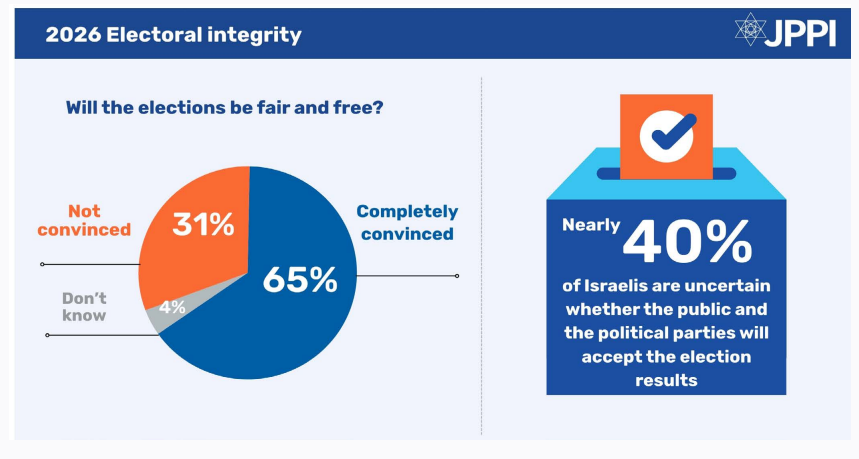

- Most Israelis expect that the 2026 elections will be fair and free, but a significant share is not convinced they will be fair and free.

- Nearly 40% of Israelis are uncertain whether the public and the parties will accept the election results.

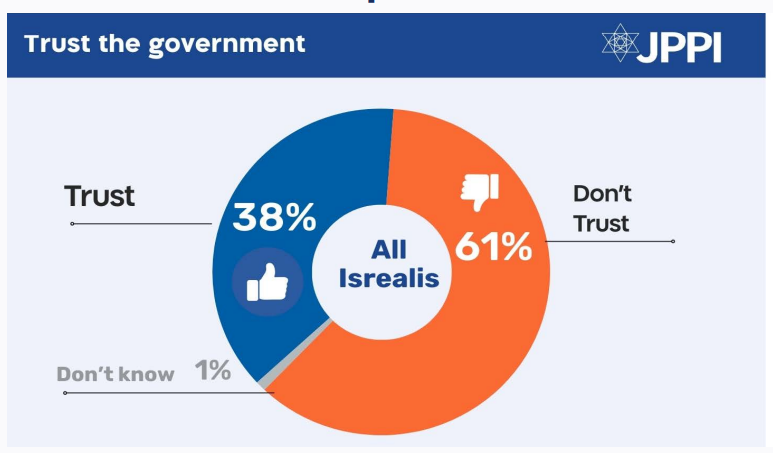

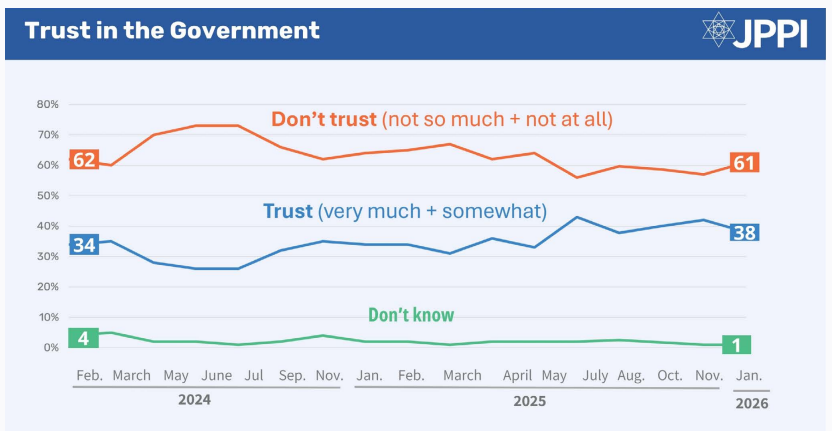

- Most Israelis do not trust the government; there has only been a slight uptick over the past two years.

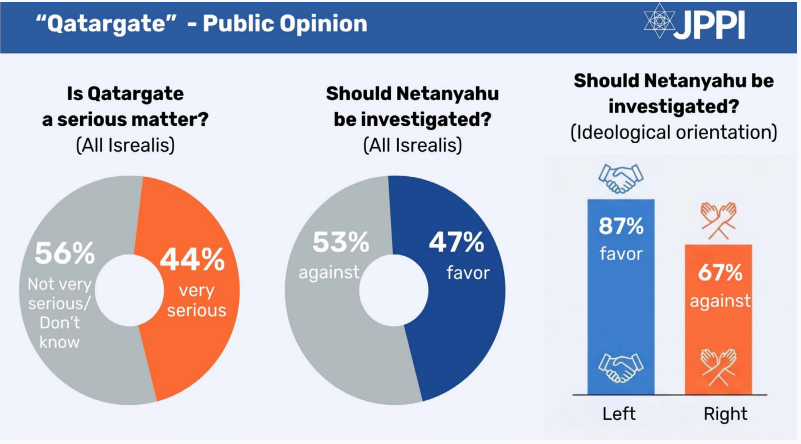

- Most view “Qatargate” as a serious affair; half think the prime minister should be investigated.

- Half of Jewish Israelis (mostly supporters of right-wing political parties) support Israeli rule in Gaza.

- There has been a consistent decline in the importance Israelis attach to the value of “striving for compromise and unity.”

- There has been a decline in the importance Jewish Israelis attach to the value of protecting the rights of minority groups.

- There has been a slight increase in the importance Israelis attach to “connection to global Western culture.”

- Israel’s strength: security ranks first, then the economy, and finally, social strength.

- Optimism has increased regarding both the country’s future and respondents’ personal futures, but they are more optimistic about their personal futures than about the country’s future.

- On the right, optimism is higher than among the center-left – both nationally and personally.

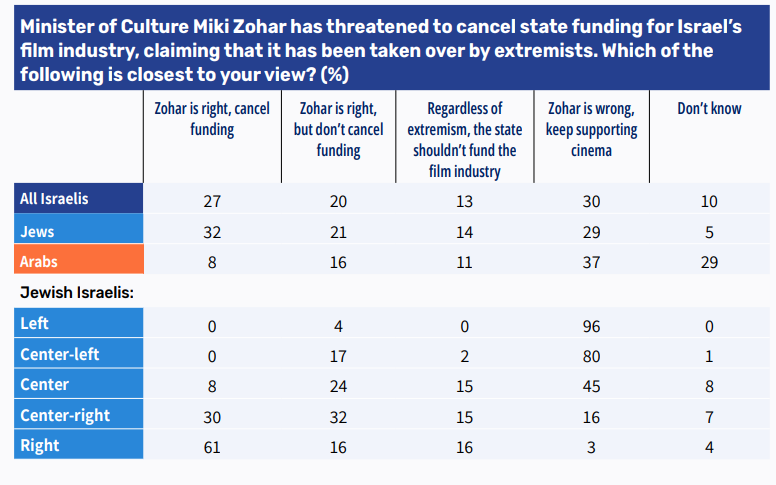

- Half support continuing financial support for Israeli cinema; two in five support canceling it.

- Most coalition voters: the Israeli film industry is extremist, and it should not be funded by the state.

To download the PDF file, click here.

2026 Elections

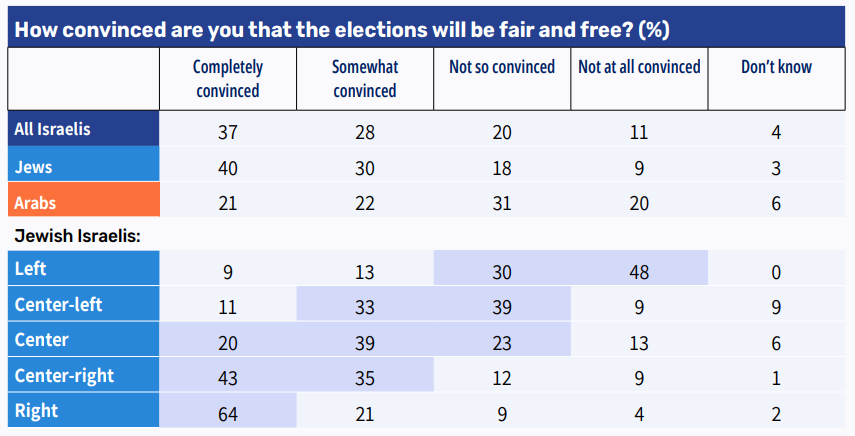

2026 is an election year in Israel, although the exact date has not yet been determined. This month, we examined whether Israelis assume the elections will be fair and free. Most Israelis (65%) do expect the elections will be fair and free, but a substantial share – about a third (31%) – are not convinced of this. Among Arab Israelis, a higher share, about half, are not convinced that the upcoming elections will be fair and free.

Respondents’ political positions heavily influence their assessment of what to expect in the elections. While most of those in the right-wing and centrist cohorts are convinced (completely convinced + somewhat convinced) that the 2026 elections will be fair and free, most respondents in the two left-wing cohorts are not convinced (not at all convinced + somewhat not convinced). In a breakdown by religiosity among Jewish Israelis, more than half of respondents in every cohort expect that the elections will be fair and free (53% of secular, 80% of traditionalist (Masorti), 89% of religious (Dati), and 95% of ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) Jews).

Most Israelis (57%) believe that the public and the political parties will accept the election results, but 27% are “not so convinced,” and one in ten (11%) is “not at all convinced.” In other words, overall, nearly four in ten Israelis are not convinced that the public and the parties will accept the results.

Here too, the share of Arab Israelis who think the election results might not be accepted by the public and the parties is higher than the share of Jews who think so. Still, more than one-third of Jewish Israelis (36%) are not sure the election results will be accepted by the public and the political parties.

Across all ideological groups, except the small left-wing cohort, at least half are convinced (completely convinced + somewhat convinced) that the public and the parties will accept the election results. However, every ideological cohort also includes a substantial share who suspect that the results may not be accepted by the public and the political parties. This is true even on the right – the largest group among Jewish respondents, with almost all respondents supporting the current coalition – where 35% are not convinced that the results will be accepted. In other words, there is a clear difference between the question of election fairness, where suspicion from the center leftward is much greater than among the right-wing cohorts, and the question of accepting the results, for which skepticism is fairly uniform across groups. It is reasonable to assume, though the survey did not inquire explicitly, that the concern among each group pertains to the possibility of non-acceptance among the other groups.

Trust in Leadership

Most Israelis (61%) do not trust the government, while a little over one-third (38%) do trust it. Among Arab Israelis, the share who do not trust the government (78%) is higher than among Jews (56%). Comparing JPPI Israeli Society Index surveys conducted over the past two years, and despite periodic fluctuations, a slight uptick in trust can be detected, but it is not very large. In all ideological groups except the right-wing cohort, a majority of respondents do not trust the government, and this majority grows as one moves leftward along the political spectrum (among the left-wing cohort, 100% do not trust the government – 91% do not trust it at all and 9% do not trust it much). Among those who self-identify as right-wing, a fifth (20%) say they have no trust in the government, and the rest trust it. A breakdown by religiosity reveals a similar pattern: most secular and traditionalist (Masorti) respondents do not trust the government, while most religious (Dati) and ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) respondents do.

Qatargate

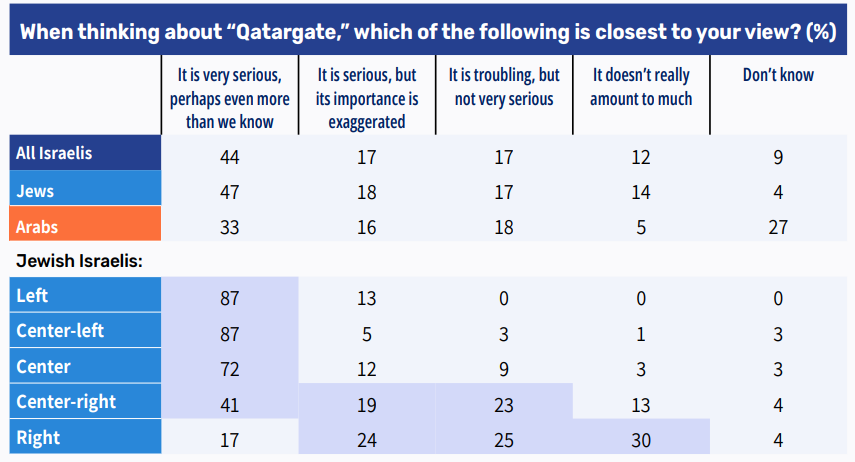

Almost half of Israelis (44%) believe the affair known as “Qatargate” is a very serious matter – “perhaps even more than we know.” One-sixth also think it is a serious affair, but that its importance is exaggerated, another sixth believe it is troubling but not very serious, and an eighth think it does not amount to much at all. In general, Arab Israelis tend to view the affair as less serious than Jewish Israelis do, and a relatively high share of Arabs (24%) answered “don’t know” to the question about the affair.

As expected, there are significant differences between ideological cohorts in how the Qatargate affair is understood. Across ideological cohorts except the right-wing group, there is a consensus that it is a serious matter (very serious + serious but perhaps exaggerated). By contrast, most of those who self-identify as right-wing think it is not very serious, or that it doesn’t amount to much at all. Broken down by voting pattern (in the 2022 elections), 59% of Religious Zionism voters and a quarter (26%) of Likud voters believe that Qatargate is a serious matter.

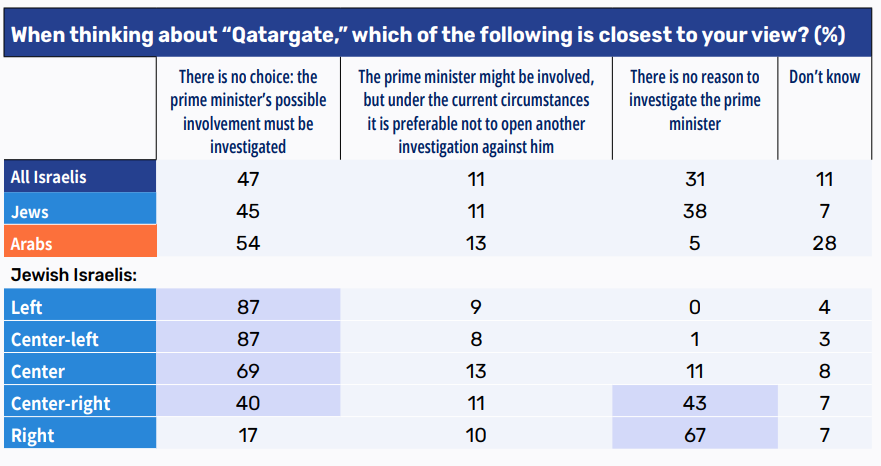

Nearly half of Israelis (47%) think an investigation of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s personal involvement in Qatargate is required. One-third think there is no reason to investigate Netanyahu’s role in this affair, which has been linked to some of his close advisers. A tenth think the prime minister might be involved, but given the current political, social, and legal situation, it is preferable not to open another investigation against him (who is currently on trial for other alleged offenses). Although Arab Israelis view Qatargate as less serious than their Jewish counterparts do, a higher share of Arabs think the prime minister’s possible involvement should be investigated.

Here too, there are significant gaps between ideological groups: among left-wing and centrist respondents, a large majority think Netanyahu’s possible involvement should be investigated, while most (67%) right-wing respondents think he should not be investigated. Just a tenth (10%) of Likud voters think the prime minister’s possible involvement should be investigated. Among those who self-identify as center-right are roughly evenly split between those who think he should and should not be investigated.

When thinking about “Qatargate,” which of the following is closest to your view? (%)

There is no choice: the prime minister’s possible involvement must be investigated The prime minister might be involved, but under the current circumstances it is preferable not to open another investigation against him There is no reason to investigate the prime minister Don’t know

Control of the Gaza Strip

The situation in Gaza has not changed significantly since the current ceasefire began, but during Prime Minister Netanyahu’s recent Florida visit to meet with President Trump, the president expressed his eagerness to move to “Phase B” of his plan to end the war and rehabilitate Gaza. Against this backdrop, this month we examined Israelis’ current preferences regarding possible governance arrangements in Gaza in the coming years. In the first question, we presented a number of options, and then we narrowed them down.

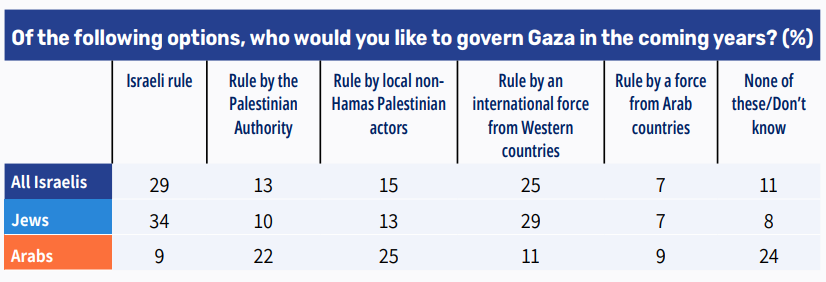

The first question presented five governance options for Gaza: nearly a third (29%) of respondents said they would like to see Israeli rule; a quarter (25%) said they would prefer rule by an international force from Western countries; a sixth (15%) chose rule by non-Hamas local Palestinian actors; an eighth (13%) chose rule by the Palestinian Authority (PA); and 7% would like to see a force from Arab countries rule. Among Arab Israelis, whose answers differ markedly from their Jewish counterparts, a quarter prefer rule by non-Hamas Palestinian actors; another quarter prefer PA rule; a quarter rejected all of the proposed options; and another quarter gave other answers.

Most respondents (63%) who self-identify as right-wing prefer Israeli rule in the Gaza Strip. Among center-right respondents, the two options receiving the broadest support were rule by an international force from Western countries (35%) and Israeli rule (30%). Most coalition party voters would like to see Israeli rule in Gaza in the coming years, while opposition party voters are split among the other options presented.

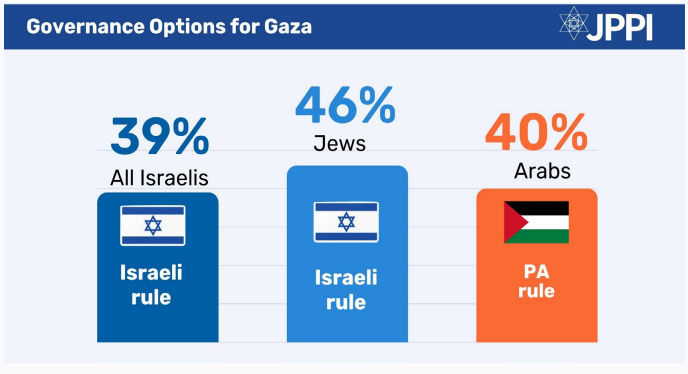

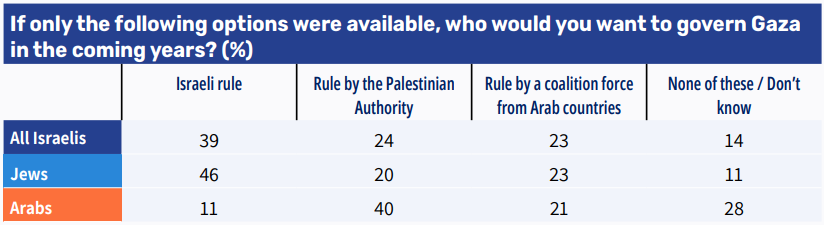

When we narrowed the options down to just three, and omitted the options of a force from Western countries (which does not seem like a realistic option) and local non-Hamas Palestinian actors (which has been Israel’s preference according to statements by some of its leaders, but so far appears difficult to implement), 39% of Israelis say they prefer Israeli rule; a quarter (24%) prefer PA rule; and another quarter (23%) prefer rule by a force from Arab countries. This narrowing makes the gaps between Jews and Arabs even more pronounced: faced with an option of Palestinian and/or Arab rule, about half of Jewish Israelis prefer Israeli rule in Gaza; a quarter prefer rule by Arab countries, and only a fifth prefer PA rule. By contrast, among Arab Israelis, 40% prefer PA rule in Gaza, a fifth would like a force from Arab countries, and just a tenth favor Israeli rule.

With only these three options, most respondents in the two right-wing groups prefer Israeli rule. There is no preference for Israeli rule in any of the other cohorts. Among centrists, a third (35%) support rule by a force from Arab countries, a quarter (27%) prefer PA rule, and a fifth (19%) favor Israeli rule in the Gaza Strip. Most respondents in the left-wing cohorts prefer PA rule. In a breakdown by religiosity, a majority or near-majority of Jewish Israelis in every religious cohort – except the secular group – prefer Israeli rule in Gaza. Among secular respondents, a third support rule by a coalition force from Arab countries, a third prefer PA rule, and a quarter favor Israeli rule.

Values

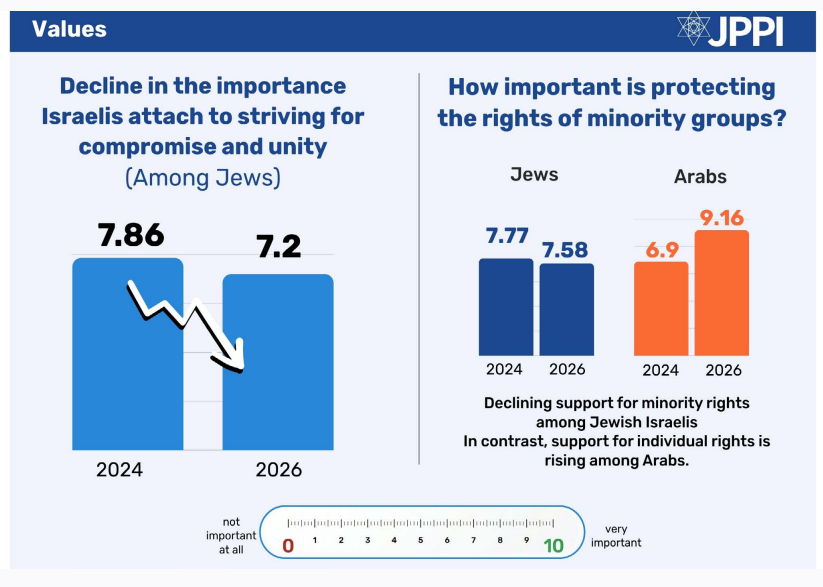

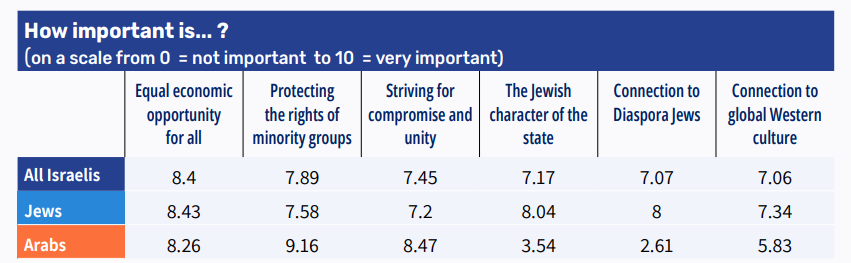

As we did in January a year ago, this month we examined the importance Israelis attach to a selection of values. Respondents were asked to rank each value on a scale from 0 (not important at all) to 10 (very important). Of the values queried, “equal economic opportunity for all” scored highest (8.4), followed by “protecting the rights of minority groups” (7.89), “striving for compromise and unity” (7.45), “the Jewish character of the state” (7.17), “connection to Diaspora Jews” (7.07), and finally “connection to Western culture” (7.06). Significant gaps were found between Jewish and Arab responses. Among Jews, the three leading values are equal economic opportunity, the Jewish character of the state, and connection to Diaspora Jewry; among Arabs, the three leading values are protecting the rights of minority groups, striving for compromise and unity, and equal economic opportunity. Jewish Israelis give striving for compromise and unity the lowest ranking (7.2). This is a finding that bears close examination, in light of the fact that in the last monthly index (December 2025) most Israelis said that social polarization is the greatest danger to Israel (out of three options offered: polarization, Iran, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict).

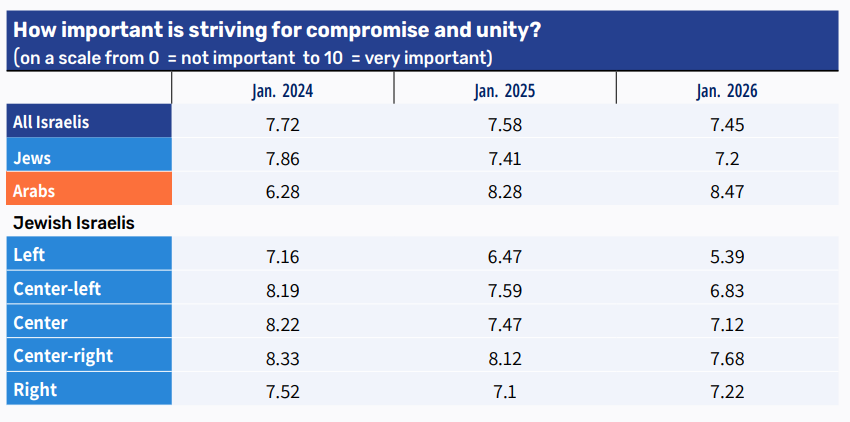

As noted, an identical question on values appeared in the January 2025 survey exactly a year ago. In fact, we have examined the importance Israelis attach to a selection of values for three consecutive years. This year, compared to previous years, we see a decline in the importance Israelis attach to striving for compromise and unity. This trend only applies to Jewish Israelis; an opposite trend emerges among Arab Israelis: an increase in the importance of striving for compromise and unity. Broken down by ideological orientation, the declining trend in assigning importance to compromise and unity appears across ideological cohorts except the right-wing group, where a slight increase was recorded this year, following a decline last year.

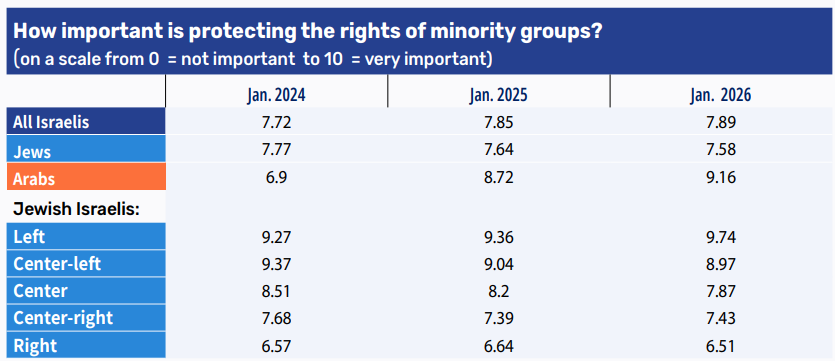

On the other hand, the importance attributed to “protecting the rights of minority groups” has increased in a slow but consistent upward trend recorded over the past two years, but this is largely driven by a substantial rise in the importance Arab Israelis attribute to the issue. In January 2024, the average score among Arabs for this value was 6.9 – a result that looks unusual in light of the following two years: this year, the average score is 9.16, and it ranks first among all the values presented to respondents. Among Jewish Israelis, an opposite trend is evident: over the past two years, there has been a slight decline in the importance attached to protecting the rights of minority groups. This decline appears in all ideological cohorts except the left-wing group, where a slight increase has been recorded over the past two years.

There has also been an increase in the importance Israelis assign to the connection with global Western culture over the past two years. This increase was recorded consistently among Jews, and in the past year, also among Arabs. It was detected among all ideological cohorts. As in previous years, the ideological breakdown shows that the further one moves leftward on the ideological spectrum, the greater the importance assigned to the connection with global Western culture. This year, the right’s average score for this value is 6.3, while the average score for all groups from the center leftward is above 8.

Israel’s Strength

Israel’s strength in different spheres was also examined this month, in an effort to draw a comparison to the situation a year ago.

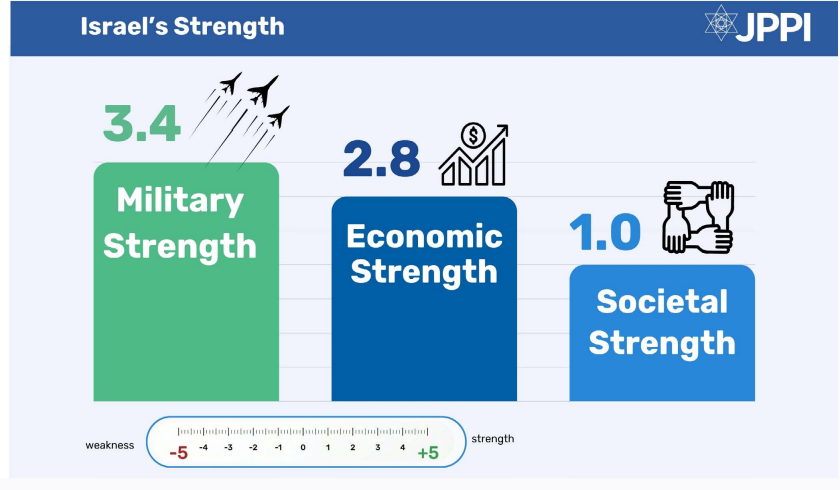

On a scale from -5 (weakness) to +5 (strength), January Israeli Society Index respondents rate Israel’s military strength at an average of 3.4. In general, Jewish Israelis tend to rate Israel’s military strength higher than Arab Israelis (3.8 versus 2.0). Still, compared to one year ago, there has been a slight decline in perceptions of Israel’s military strength among both Jews and Arabs. This result may seem surprising given the outcomes of the 12-day Iran campaign about six months ago, but perhaps it can be explained in light of the not-entirely-clear outcome at the end of the campaign in Gaza. But compared to two years ago (January 2024), there was no significant change this year. Broken down by ideological orientation, we see that the right rates Israel’s military strength significantly higher than either the center or the left. While the center-left’s average rating is 3.4, the average rating among the right is 4.3. Compared to January 2024, about three months after the start of the October 7 war, when this question was first asked, there has been a decline in perceived military strength on the left and an increase on the right.

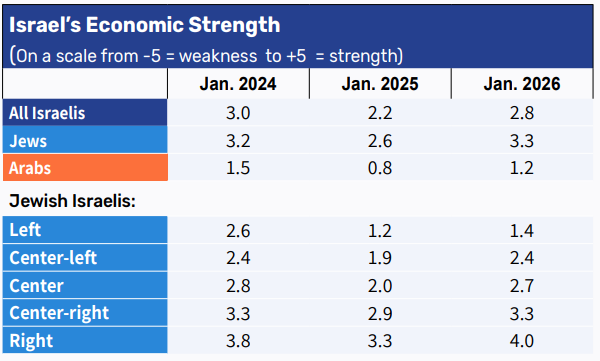

Israelis rate the country’s economic strength, on average, 2.8 – positive, but lower than the assessment of military strength (3.4). Jewish Israelis tend to rate Israel’s economic strength higher than Arab Israelis (3.3 versus 1.2). Compared to last year, there has been a positive increase in how Israel’s economic strength is perceived by Jews and Arabs alike. But the assessment of Israel’s economic strength has hardly changed when compared to findings from two years ago, and among Arab Israelis, it has declined slightly. In this context as well, the left tends to rate Israel’s economic strength lower than the right. While the left recorded an average of 1.4 this month, the right recorded an average of 4.0. The data also shows that, compared to January 2024, no significant change has occurred in how most ideological cohorts rate Israel’s economic strength.

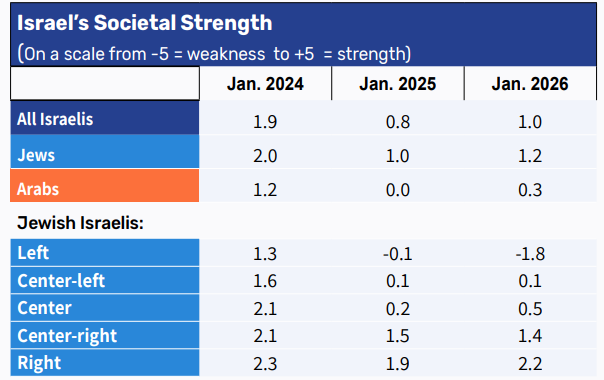

The strength of Israel’s society received the lowest score of the three categories measured. Israelis, on average, rated it 1.0 – 1.2 among Jews, and 0.3 among Arabs. This is to say that Israelis regard Israel’s military strength as greater than its economic strength, and its economic strength as greater than its societal strength. Compared to a year ago, there has been a slight uptick in assessments of social strength among both Jews and Arabs. However, when compared to two years ago, there has been a significant decline in how the strength of Israeli society is assessed across all respondent cohorts. This phenomenon may be attributed to the Israeli unity felt in January 2024, close to the start of the October 7 war, when Israeli society mobilized to respond to national challenges, and social polarization temporarily diminished.

Here too, differences are evident between the right and the left, but the assessment is fairly low among all cohorts. As one moves rightward along the ideological spectrum, the perception of societal strength gradually rises.

Optimism/Pessimism

Another trend question asked this month examined respondents’ level of optimism with respect to both their personal future and the country’s future. Again, respondents were asked to rate their feelings on a scale from -5 (pessimism) to +5 (optimism) with 0 marking the neutral midpoint between the two.

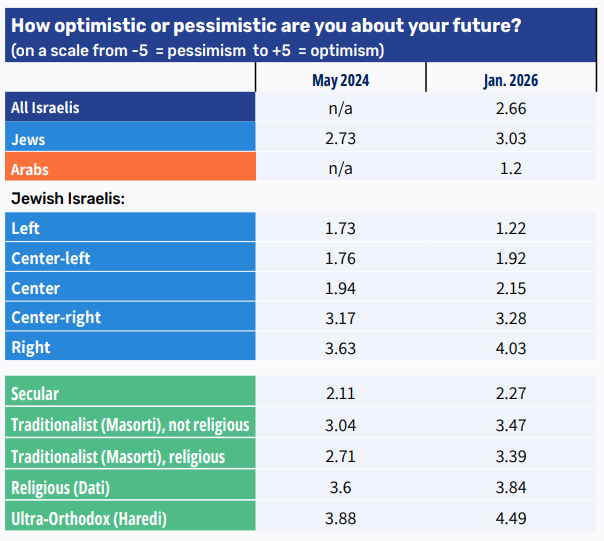

The average score regarding respondents’ personal future is 2.66, indicating relatively high optimism. Among Jewish Israelis, the average score is higher (3.03) than among Arabs (1.2). Compared to findings from May 2024, half a year after the start of the October 7 war, optimism among Jewish Israelis has risen from 2.73 to 3.03.

Higher optimism levels were found among the right compared to the center and left. The trend is clear: the further one moves rightward along the ideological spectrum, the greater the optimism. The same trend was apparent in May 2024, and compared to the averages recorded then, optimism has increased in all ideological cohorts except the left-wing group. A similar trend emerges when broken down by religiosity: the further one moves along the religiosity spectrum from secular toward ultra-Orthodox, the greater the respondents’ optimism about their personal future. Here too, comparing responses from a year and a half ago with those recorded this month, optimism has increased among all religious cohorts.

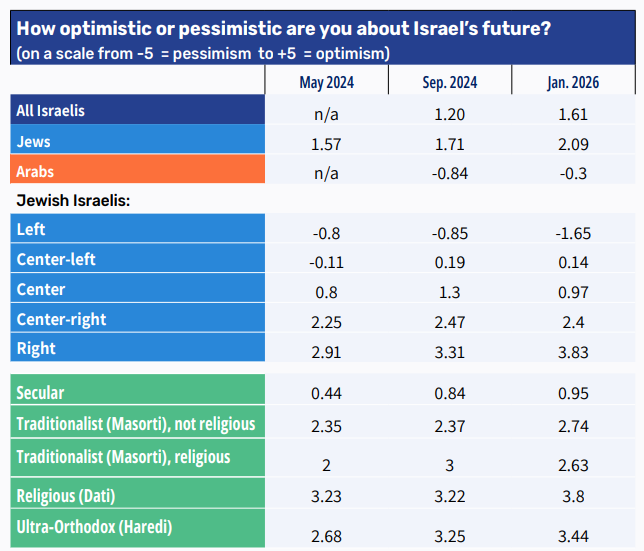

All Israelis – Jews and Arabs – are more optimistic about their personal future than about the country’s future. Still, over the past year, optimism about Israel’s future has increased. In September 2024, the average optimism level for all Israelis was 1.2; this month it stands at 1.61. The increase in optimism was recorded among both Jews (an increase from 1.71 to 2.06) and Arabs (an increase from -0.84 to -0.30).

Regarding Israel’s future as well, the further one moves rightward along the ideological spectrum, the greater the optimism. The optimism gaps between right and left are greater with respect to the country’s future than the respondents’ personal future. The gap between ideological extremes was 2.81 with respect to personal optimism, but 5.48 regarding Israel’s future. This is due, among other things, to the pessimistic assessment of the far-left cohort (a small group) regarding Israel’s future (-1.65).

A similar trend emerges from a breakdown by religiosity, but with smaller gaps: the further one moves from the secular end of the religious spectrum toward the Haredi end, the greater respondents’ optimism about the future of the State of Israel. In this breakdown, the gap between the extremes is 2.49, compared to 2.22 for the personal-future question. Over time, an upward trend in optimism was recorded compared to earlier months in which we examined this question. This trend may be attributed to the end of the war (the two previous samples were taken during it), or even to the approaching elections, which allow some Israelis to hope for change.

Support for Israeli Cinema

In the wake of the past month’s confrontations between the Minister of Culture, Miki Zohar, and Israeli filmmakers – against the backdrop of Zohar’s decision to award prizes outside the established Ophir Awards framework (Israel’s Oscars) – we examined public attitudes on this issue. Zohar explicitly threatened to cancel the state’s budget allocation for Israeli film, claiming that there has been an “extremist takeover of the cinema industry in Israel.”

Half of Israelis agree with Zohar about extremism within the film industry; a quarter of them (27%) also think this is a reason to cancel support for Israeli cinema, while a fifth (20%) think it is not a reason to cancel state support. One-third of Israelis (30%) think Zohar is wrong about extremism in the film industry and that it is important that Israel continue to support cinema. An eighth think that regardless of the question of extremism, there is no reason for the state to financially support this industry.

A breakdown by ideological orientation reveals significant gaps in answers depending on political affiliation. While most respondents in the left-wing and centrist cohorts think Zohar is wrong and that Israel must continue supporting cinema, on the right, a clear difference emerges between center-right and right-wing respondents. A third of the center-right cohort think the Israeli film industry is tainted with extremism, and, therefore, government support should be canceled; another third think it has extremist elements but that is not reason enough to cancel the support; a sixth think that regardless of extremism, the state should not support cinema; and another sixth think Zohar is wrong about extremism and that it is important for Israel to continue supporting cinema. Among those who self-identify as right-wing, a majority believe Zohar is right and that government support of cinema should cease. Accordingly, most supporters of the current coalition (based on their vote in the 2022 elections) think there has been an “extremist takeover” of the Israeli film industry and that support for it should be canceled. By contrast, most opposition supporters think Zohar is wrong and that it is important for the government to continue supporting Israeli cinema.