The War and the Day After, Trust in the Nation’s Leadership and the IDF, Antisemitism and Foreign Relations, Education and Society, Public Sentiment ahead of Rosh Hashana.

Main Findings:

- Eight in ten Israelis feel that the past year was “bad” or “not good” for Israeli society.

- Six in ten think the year was “bad” or “not good” for Israel’s economy and its security.

- A large majority of Israelis think things are deteriorating worldwide.

- A large majority of Israelis believe Israel is on a downward trajectory.

- Nevertheless, a small minority of Israelis think Israel’s future will be “better.”

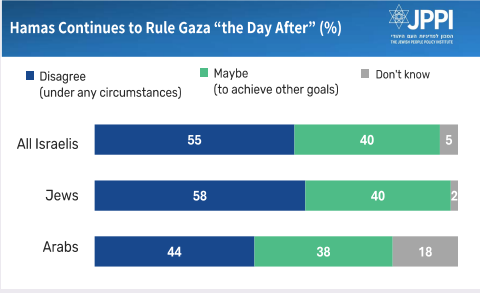

- Most Israelis are unwilling “under any circumstances” to accept continued Hamas rule in Gaza.

- Most Israelis are unwilling “under any circumstances” to give up on a security perimeter in Gaza.

- Most Israelis are willing to accept Palestinian Authority rule in Gaza.

- Most Israelis are willing to accept an Israeli occupation and military administration of Gaza.

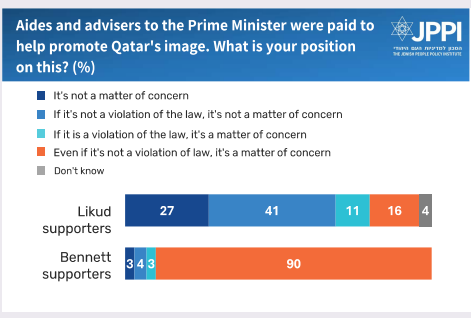

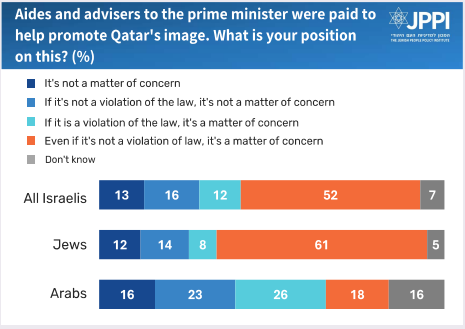

- Most say the Qatargate affair is troubling “even if it was not unlawful.”

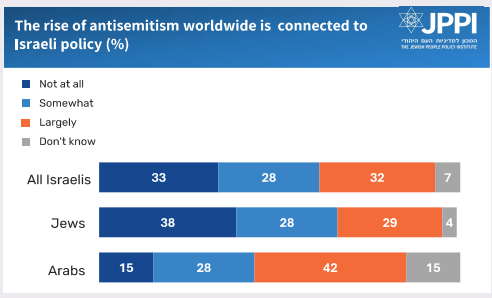

- Most say the rise of antisemitism worldwide is partly “due to Israeli policy.”

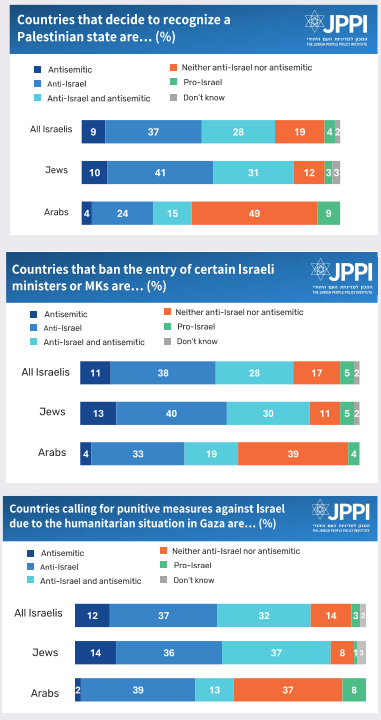

- Most maintain that countries that recognize a Palestinian state are acting in an anti-Israel and/or antisemitic manner.

- Most rate the Israeli education system as mediocre or “not good.”

- Religious and traditionalist Jewish Israelis support adding more Jewish studies to the education curricula.

- A high percentage of secular Jewish Israelis strongly support adding civics and reducing Jewish studies in schools.

- Literature stands out as a subject many would cut back (if cuts were required).

To download the PDF file, click here.

The War and the Day After

JPPI’s September Israeli Society Index survey was conducted in the weeks leading up to Rosh Hashana, the Jewish New Year, nearly two years after the war broke out in October 2023. Context is important for understanding its findings: Israel was on the verge of intensifying the Gaza campaign – unless an agreement was reached first. At the same time, the country continued to be the target of significant international criticism, which will likely peak this month with the 2025 UN General Assembly.

Sense of Victory

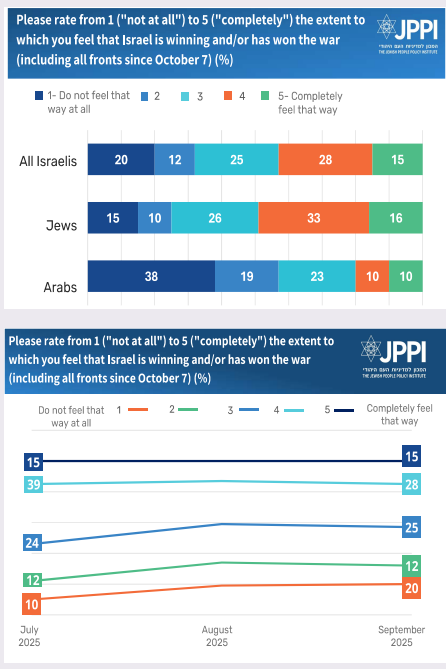

A fifth of the Israeli public (20%) does not think “Israel is winning and/or has won the war overall,” and only 15% believe that Israel is fully winning. On a scale of 1 (not winning) to 5 (winning), most Israelis chose the middle of the scale – 25% chose “3” while another 28% chose “4”. Among Jewish Israelis, 16% strongly feel that Israel is winning, while a third chose “4.” That is, nearly half of Jewish Israelis express a sense of winning. Among Arab Israelis, 38% do not at all sense that Israel is winning the war, and only 10% rated this as “5”. Those in the Arab sector who chose “4” or “5” were mainly Druze respondents.

Compared with July–August, this month shows a slight erosion of the sense of achievement, perhaps because the Iran campaign – widely viewed as a success – has receded in time. In July, 18% of the general public said they strongly felt that Israel is winning; in August 17% gave this response. But in September, the share dropped to 15%. At the same time, the percentage who do not at all think Israel is winning rose from 17% in July to 20% in September. As the war continues without tangible gains, the public’s sense of victory erodes.

As in previous months, the sense of winning the war correlates with Ideological orientation and voting pattern. Among those who self-identify as right-wing, 68% rated their sense of victory as 4 or 5; among centrists, it was less than half (33%); among the left (the smallest Jewish-sector cohort), the share was 17%.

A Deal or More Fighting

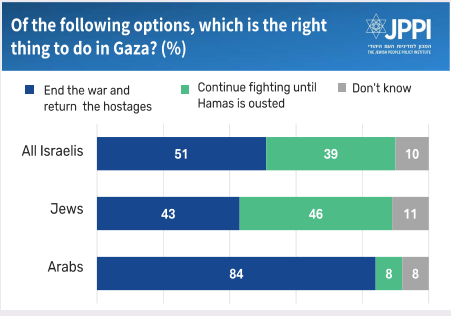

As last month, we again asked a deliberately simplistic – and so also imperfect – either/or question to track a persistent dilemma: Israel should aim to end the war and return the hostages even if Hamas remains in power in the Gaza Strip, or Israel should continue the war to oust Hamas, even if that means no hostage deal.

This month, a small majority prefers to end the war and return the hostages, even at the price of Hamas remaining in power, and 39% prefer continuing to fight until Hamas is ousted (the rest don’t know). This majority rests heavily on overwhelming Arab support for ending the war; Jews are almost evenly split (43% support a deal, 46% prefer continued fighting). The question was worded slightly differently this month to emphasize the abstract nature of the dilemma, but the findings were quite similar to previous months nonetheless. In August, 54% supported ending the war (51% in September), and just over a third favored the war’s continuation (37% versus 39%).

We then probed which terms Israelis might accept for a future arrangement in the Strip. Some respondents gave contradictory answers, so the data does not always yield a fully coherent yes/no picture. Still, from the range of options offered, we can discern which elements could obstruct or enable reaching an arrangement. For each option, respondents were able to express support, support conditionally for other goals, or oppose under any circumstances.

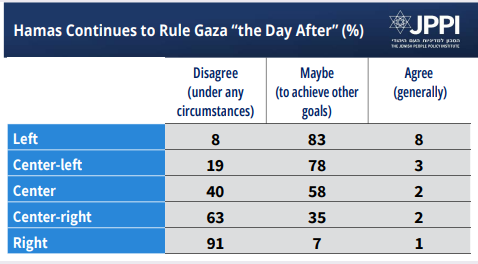

A majority would not agree to Hamas continuing to control Gaza on the day after the war under any circumstances – even though only a minority of Arabs choose this response. Among Jewish respondents, 55% said they would not, under any circumstances, agree to Hamas remaining in power. Forty percent said “maybe – to achieve other goals (likely the return of the hostages and an end to the war), while 5% would generally agree to continued Hamas rule.

Regarding the dilemma of Hamas remaining in power, we found a very large divide based on ideological orientation. On the right, an overwhelming majority would not agree to this under any circumstances, the same is true for a substantial majority among the center-right. A majority of centrists and those on the left would consider agreeing to such a possibility “to achieve other goals.” The answers of Druze respondents mirrored those of the center-right (although they are a small cohort in the survey sample). Unsurprisingly, coalition party voters strongly support the coalition’s declared position – that removing Hamas from power is a non-negotiable condition for ending the war.

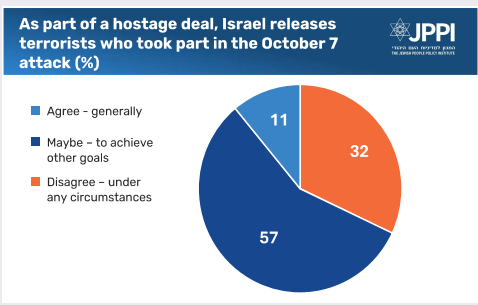

The next “circumstances” question pertained to a hostage deal that includes the release of “terrorists who took part in the October 7 attack.” Most Israelis would agree to this (11%) or “maybe” agree to this (57%). This majority exists among both Jews and Arabs. Among Jewish Israelis, only the right-wing cohort comprises a majority opposing this scenario, while both the center-right and left-wing cohorts comprise a majority willing to consider paying such a price in exchange for the return of the hostages.

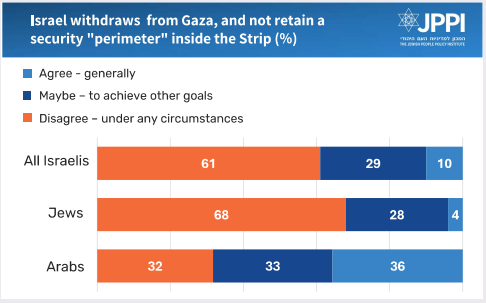

A significant majority of the Jewish public opposes the possibility of withdrawal to the Gaza border without retaining a security “perimeter” inside the Strip. Nearly seven in ten Jewish Israelis would not agree to such a scenario “under any circumstances,” while a quarter are willing to consider the possibility, and a third would agree to it. Broken down by ideological orientation, Jews in the centrist and right-wing cohorts (center-right and right) oppose an Israeli withdrawal without retaining a security perimeter. In the left-wing cohorts (center-left and left) there is support for such a withdrawal in exchange for other goals. Among respondents who currently intend to vote for The Democrats, Yesh Atid, or the new party headed by Gadi Eisenkot, there is a noticeable willingness to forgo a security perimeter inside Gaza.

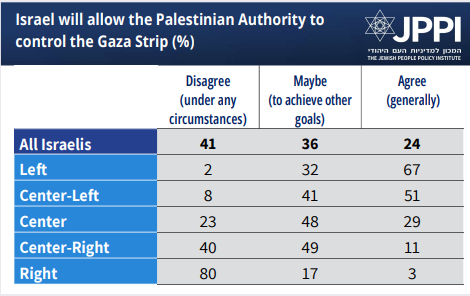

A 60% majority is willing to accept or consider the possibility of Israel allowing the Palestinian Authority to govern the Gaza Strip. Forty-one percent oppose such a scenario under any circumstances. The findings for this question show no great difference between Jewish and Arab Israelis. Response differences are mainly evident among Jews based on ideological orientation. On the right, there is overwhelming opposition to the idea; the center-right camp shows significant opposition, but a majority are willing to consider the possibility. The centrist and left-wing cohorts show conditional or full support for the possibility. Among Likud voters (the prime minister’s party), 73% oppose the idea under any circumstances, and the situation is similar for supporters of all the other coalition parties.

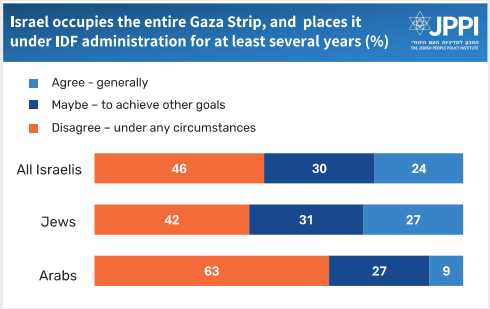

The last scenario offered relates to an arrangement for Gaza that would include Israeli occupation and military administration for several years at least. A small majority of Israelis would support such a scenario: a quarter support it in any case, a third support it for the sake of achieving other goals, and slightly less than half would oppose it. Opposition – as expected – is much higher among Arab Israelis (63%), compared to 42% among Jews. A majority of the centrist and left-wing cohorts oppose this possibility, while a majority in the right-wing cohorts support it. The strongest support for occupation and military administration, with no reservations, is found among supporters of the Religious Zionism and Otzma Yehudit parties.

Trust in the Leadership and the IDF

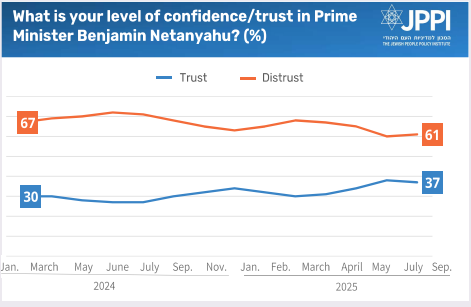

The question of trust in Israel’s political and military leadership remains central to the country’s public discourse. If there is an area where the monthly surveys have shown near-constant stability over many months, it is confidence in Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, which remains low in September 2025. Given the (sometimes public) clashes between the political leadership and the senior military echelon, especially the chief of staff, it is notable that public trust in Netanyahu is lower than it is in the IDF.

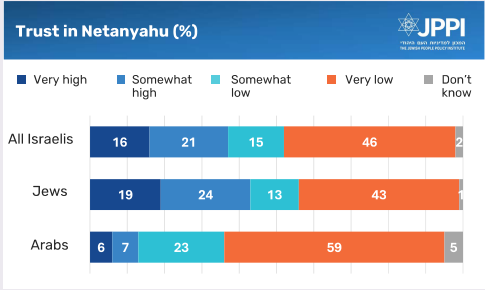

This month, overall, 37% of Israelis trust Netanyahu – a figure identical to July’s. However, the share who say their trust in him is “somewhat high” rose this month, while the percentage who say it is “very high” shrank. In September, nearly half of Israelis (46%) said their trust in the prime minister was very low. Only a third reported trusting him (16% “very high” and 21% “somewhat high”). Among Jews, the picture is slightly better: 43% say their trust in Netanyahu is very low, while 19% their trust in him is very high. Among Arabs, nearly six in ten (59%) express a total lack of trust in Netanyahu, with only 6% (notably all Christians or Druze) saying it is high.

Compared to previous months, we find relative stability, although trust in Netanyahu ticked up slightly in the wake of the 12-day Iran campaign and remained elevated throughout the summer.

Methodologically, it should be recalled that a few months ago, after an internal assessment, the wording of trust/confidence questions was changed: we began to ask respondents whether they “trust/do not trust” leaders and organizations (rather than inquiring about their “level of confidence,” as in earlier versions).

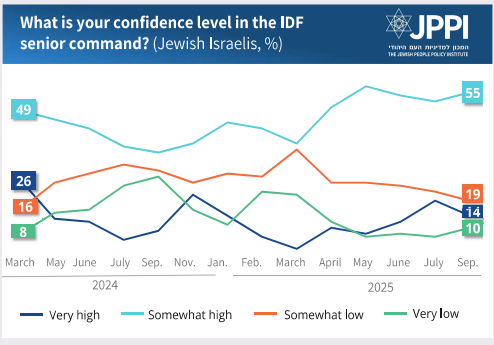

The IDF senior command enjoys much higher public trust than the political leadership in general, and the prime minister in particular. Sixty-two percent of the general public trusts the IDF senior command (14% say their trust is high, while 48% say they “somewhat” trust it). Among Jewish Israelis, trust is even higher – 69%. Sixty-one percent of Arab Israelis do not trust the IDF senior command; only a minority (33%) do.

Compared with June and July (65% trust), September’s 62% marks a dip. The decline is especially noticeable among Jewish Israelis, supporters of the right and center-right, possibly reflecting discord between the political and the military echelons regarding prosecution of the war in Gaza. It may also reflect the ongoing crisis regarding ultra-Orthodox conscription. Shas and United Torah Judaism supporters express the lowest trust levels in the IDF senior command, alongside Otzma Yehudit supporters.

“Qatargate”

The September Israeli Society Index survey included a question about what the media calls “Qatargate” – a scandal in which connections came to light between Israelis close to the prime minister and Qatari funding or influencers. The affair is still under investigation. The survey found that a majority of Israelis (52%) think it is concerning even if it emerges, after the investigation, that no laws were broken. Twelve percent would find it concerning only if unlawful behavior could be proven. Nearly a third (29%) of respondents are unconcerned by the affair. Among Jewish Israelis, 61% think Qatargate is concerning in any case; among Arabs – 35%.

Broken down by political affiliation, Likud supporters are relatively unconcerned by the affair, while supporters of all the opposition parties and some of the coalition parties (Religious Zionism voters in particular – 47%) are concerned by it. In a comparison of the two parties that currently enjoy the most support, Likud and Naftali Bennett’s (still unnamed) party, we see how political orientation affects attitudes toward Qatargate.

Antisemitism and Foreign Relations

The war is not only being waged on the battlefield or in domestic politics – it also places Israel under an international spotlight. Alongside political and media criticism, recent years have brought a rise in antisemitism worldwide. The September 2025 survey probed Israelis’ views of this situation, the link (if any) to Israeli policy, attitudes regarding possible policy change, and international measures such as academic boycotts or entry prohibitions placed on Israeli ministers.

Is the rise in global antisemitism the result of Israeli policy? Most Israelis think there is a connection between antisemitism and Israeli policy, to a large extent or to some extent. Among Arab Israelis, a large majority say so, while among Jewish Israelis, a smaller majority draw the connection. About a third of Israelis believe that today’s rising antisemitism is “not at all due to Israeli policy” (38% of Jews).

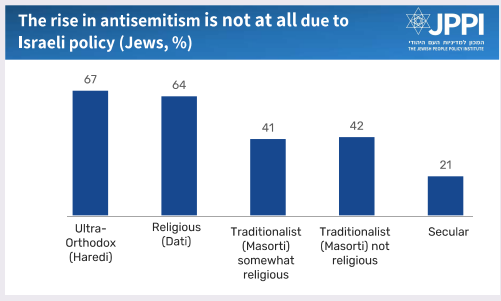

Large differences are evident when responses are broken down by ideological orientation and religiosity level. In general, the further right on the political spectrum and the more religious, the higher the percentage of respondents who think there is no relationship between Israeli policy and rising antisemitism. Among religious and ultra-religious Jews, believe that rising antisemitism is not due to Israeli policy. Among secular Jews, by contrast, 43% say that the growth in antisemitism is largely due to Israeli policy, while another 32% think it is somewhat due to Israeli policy.

Despite the majority who see a linkage, about 47% of Israelis say Israel should not change its policy because of rising antisemitism. Among Jewish Israelis, an absolute majority (56%) feel this way. Among Arab Israelis, only 11% hold this view, while 48% say they “don’t know.” What this means is that a sizeable percentage of Israelis think that rising antisemitism is an outcome of Israeli policy, but that this is not a reason to alter policy. Even among respondents whose confidence in Israeli policy or in the Israeli government is relatively low, there isn’t a majority who think Israel should change its policies “due to the rise in antisemitism” (some may favor policy change for other reasons). Opposition party supporters tend to think that policy ought to be somewhat modified. Coalition party supporters tend to see no need to change Israeli policy at all. For example, 93% of Likud voters say policy should not be changed. Thirty-seven percent of Yisrael Beiteinu also say that policy should not be changed, but 41% say that it should be altered “somewhat” due to antisemitism.

Foreign Countries and Israel

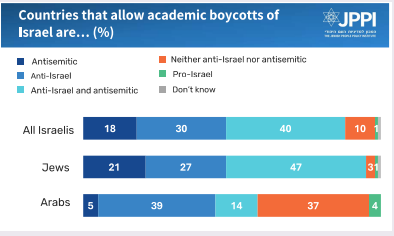

Ahead of the 2025 UN General Assembly, where several key countries (France, Australia, the UK, and others) are expected to advance an initiative to recognize a Palestinian state, we examined whether Israelis accept the claim voiced by some high-ranking Israeli officials that such an initiative is anti-Israel and/or antisemitic. Overall, a large majority of Israelis agree with this contention in one form or another. A quarter see the initiative as anti-Israel and antisemitic, over a third regard it as anti-Israel, and a tenth as antisemitic. Less than a quarter of Israelis believe that recognition of a Palestinian state at this time is neither anti-Israel nor antisemitic, and only a small percentage (4% of all Israelis, a tenth of Arab Israelis) regard it as a pro-Israel act.

The center-left, centrist, center-right cohorts, tend to consider recognition of a Palestinian state as primarily an anti-Israel act. The right-wing cohort, the largest of all Israeli cohorts, tend to regard such recognition as both anti-Israel and antisemitic. The left-wing cohort is the only one with a majority who feel that recognition of a Palestinian state is neither anti-Israel nor antisemitic, but it is relatively few in number (7% of all Jewish Israelis).

Following implicit or explicit bans on visits by Israeli ministers and Knesset members to several countries (recently, a trip by MK Simcha Rotman to Australia was cancelled), we asked how Israelis view such prohibitions. The responses to this question are similar to those regarding recognition of a Palestinian state. The main difference is found among Arab Israelis, who more often view such prohibitions as anti-Israel compared to recognition of a Palestinian state.

The percentage of Israelis who believe that countries “that call for punitive measures against Israel due to the humanitarian situation in Gaza” are acting in an anti-Israel and/or antisemitic manner is also high.

Another question in the vein related to academic boycotts of Israeli institutions. The percentage of Israelis who consider such actions antisemitic (rather than as only anti-Israel) again increased. Nearly half of Jewish Israelis regard such boycotts as both antisemitic and anti-Israel, while the share regarding them as solely antisemitic rises to 21% of Jewish respondents.

Education and Society

With the start of the new school year, the September Israeli Society Index survey once again queried respondent views regarding Israeli education – satisfaction levels, types of schools, and preferences regarding the addition or reduction of study hours in various subject areas. The picture obtained illustrates differing value systems between the cohorts.

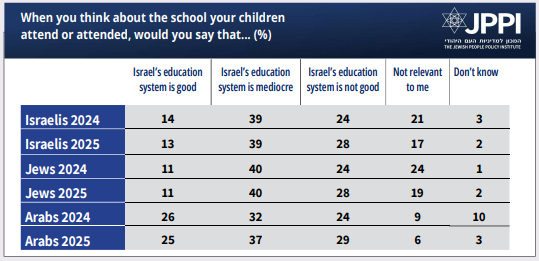

The first question on Israeli education examined overall satisfaction with the system. Only 13% of respondents believe the education system “good.” This finding is nearly identical to how the same question posed last September (2024). About 40% rate the education system as “medicore,” and a quarter think it is “not good.” Notably, a high percentage chose not to answer the question (primarily non-Jewish respondents).

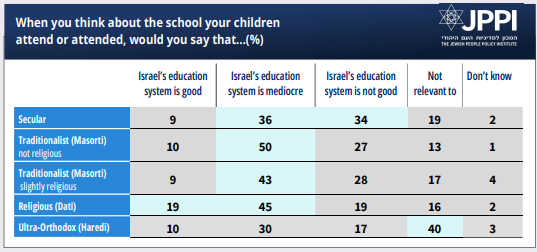

Because Israel’s Jewish education system is segmented by religiosity, we examined parent satisfaction broken down by sector. Overall, a sizeable proportion of the ultra-Orthodox gave the “not relevant to me” response, whether due to their young age, or because their children do not attend Israeli state schools (but rather private ultra-Orthodox institutions). Religious (Dati) respondents are more satisfied with the (state-religious) education system than secular and traditionalist (Masorti) respondents (the vast majority of whom send their children to state schools, except for some of the “Masorti-somewhat religious” respondents). A fifth of religious Israelis think the education system is good, double the share of other cohorts. By contrast, 34% of secular Israelis think Israeli education is not good – a percentage significantly higher than for religious Israelis, and also higher than for Masorti Israelis. Among Arab respondents, Christians stand out for their share who think the education system is “not good” (38%). Among Muslims, who constitute the vast majority of Arab Israelis, 62% rate the education system as “medicore.”

What Should Be Taught?

In two parallel questions we asked which subject areas Israelis would reinforce, and which they would cut, if they could (or were required to) to add or subtract three teaching hours to/from the curriculum. The question: “If you could add or cut three teaching hours to/from all Israeli schools, which of the following subject areas would you reinforce/cut back as requirements for all students?” Jews were given the option to add or reduce study hours in Jewish studies; Arabs were given the corresponding option of adding or reducing hours in religious studies. The following table shows, for all Israelis and for Jews and Arabs separately, which subjects would get an additional three teaching hours, and which should be cut back by three teaching hours.

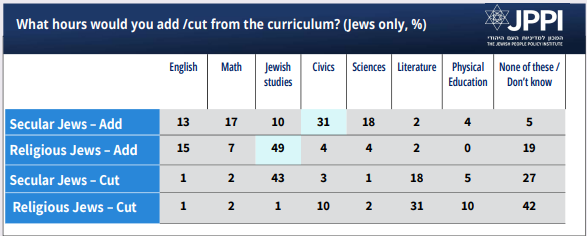

Judaism is both the subject for which Jewish Israelis of various stripes most want to add hours for, and the subject that they most favor cutting back (along with another study subject). When broken down by religiosity level, we clearly see the divide. The division over Jewish studies reflects the cultural polarization in Israeli society.

Both Jews and Arabs are prepared to add hours to the curriculum but have trouble naming the subjects for which they would reduce hours. Many more respondents answered None of these/Don’t know regarding reductions than regarding additions.

A high percentage of Jews would choose to cut back on “literature,” which in this questionnaire represents “the humanities.”

A comparison between the secular cohort, nearly all of whom study in the state education system, and the (smaller) religious cohort (nearly all of whom study in the state-religious education system) shows the difference in choice of subjects to be cut back or reinforced. The question did not try to determine how respondents would add or subtract study hours “for their children,” but rather the study hours they think should be added or cut “for all Israeli schools.” That is, when the respondents say that hours should be added for English, or cut back for civics, this is because they feel that the entire system needs this addition or can tolerate this cutback.

The subject area that the largest share of respondents think should have additional hours – while substantially outstripping other subject areas – differs between the religious and the secular. Among the secular, a third would add civics hours in all schools. Among the religious, half would add Jewish studies hours in all schools. In both cases, the answers seem to reflect an ideological assessment of the needs of Israeli society.

When respondents were asked to slash study hours, we again found highly significant disparities based on religiosity level, and the specific education system in which their children are enrolled. Over half of secular respondents would cut back on Jewish studies. Over half of religious respondents would cut back on literature studies (again, note that nearly half of the religious respondents did not manage, or did not want, to answer the question about cutbacks).

The following table reflects the major disparities between cohorts of more definitive views. The traditionalist (Masorti) cohorts, which account for a third of Israel’s Jewish population, express less definitive positions regarding study-hour distribution. For instance, 27% of non-religious traditionalists would add hours for Jewish studies. This is more than double the share of secular Jews who would do so, and half the share of religious Jews who would do so. Jewish studies is (for both traditionalist cohorts: non-religious and somewhat religious) the subject area that most merits additional study hours compared with other disciplines. On the question of cutbacks, traditionalists, like religious respondents, had trouble answering (about half do not respond). Among those who did respond, there was a clear preference for slashing literature hours.

Hopes for the New Year

With the approach of Rosh Hashana, we look at how Israelis assess the past year and look ahead to the coming year. The bottom line is unsurprising: Israelis are entering the new year with a sense of pessimism, both about Israel and the wider world.

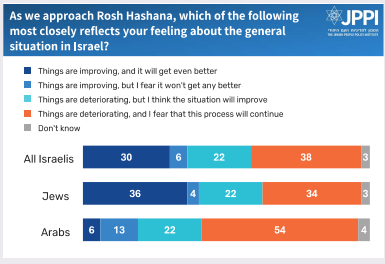

Less than a third of all Israelis, and a third of Jews, feel that in Israel “things are already improving, and will get even better.” Another 22% feel that things are deteriorating in Israel, but the situation will improve.” That is: half of Israelis think the future will be better, but only a little more than half feel that the improvement has already begun. More than half of Arab Israelis and a third of Jewish Israelis perceive a deterioration and are not optimistic about the prospects of escaping it.

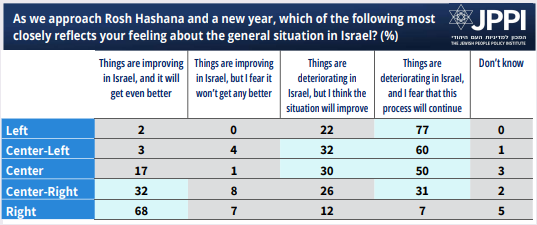

Respondents’ degree of confidence that things will improve is strongly linked to their ideological orientation and identity group affiliation. Arab Israelis are more pessimistic than their Jewish counterparts. Among Jews, the right-wing cohort is exceptionally optimistic, while the center-right exhibits similar shares of optimism and pessimism (with the addition of those who perceive deterioration but hope for improvement. A majority in the centrist and left-wing cohorts tend toward pessimism.

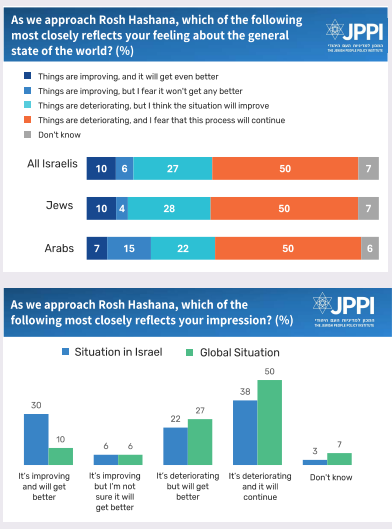

The Global Situation

A stronger sense of pessimism emerges when Israelis are asked about the situation in the world as a whole. Half feel that the world is deteriorating, and fear that the deterioration process will continue. Another quarter think the world is deteriorating but things will improve in the future. Israeli Jews and Arabs display quite similar assessments of the state of the world.

A comparison of Israelis’ views on the situation in Israel and in the world as a whole indicates that Israelis have greater confidence in Israel’s ability to generate a better future for itself than the rest of the world.

The Past Year

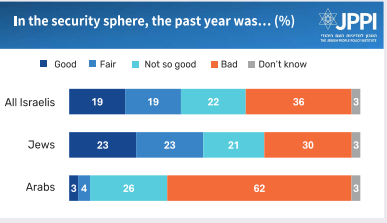

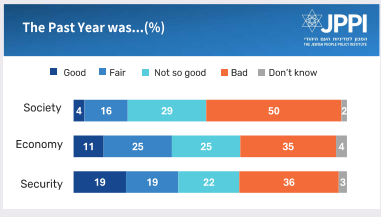

We attempted to sum up Israel’s situation over the past year by examining three areas, with an identical question about each: Was the past year good, fair, not so good, or bad? The areas we asked respondents about were security, the economy, and society. It is clear, despite the continuation of the war, that the area assessed as worst is the social sphere. Eight in ten Israelis feel that the past year was bad or not so good from a social perspective. Overall, Israelis sum up the year as “not good” from both the security and economic perspectives – six in ten Israelis rate the past year as bad or not so good.

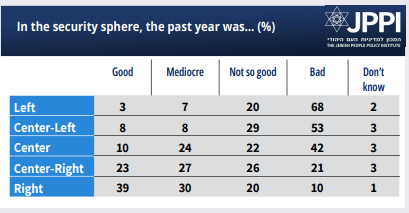

There is a very large disparity in the responses of Jews and Arabs regarding security. A large majority of Arabs feel that the past year was bad or not so good in the security sphere. Half of Israel’s Jews feel that the past year was good or fair, while half rate it as bad or not so good.

Jews rate the past year’s security situation in accordance with their ideological orientation. The right-wing cohort comprises a majority who say the year was good or fair in terms of security. The center-right cohort is nearly evenly divided on this question, while a majority of those in the center and left-wing along the ideological spectrum feel that the past year was bad or not good in terms of security.

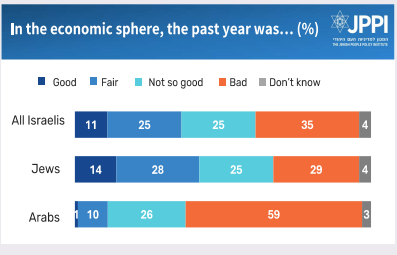

Israelis are also somewhat divided along ideological lines regarding the economic situation. Most Israelis feel that the past year was not good economically. However, this majority does not include those who self-identify as right-wing, 27% of whom say the year was good from an economic point of view, and 40% of whom say it was fair. A majority of the center-right cohort, by contrast, tend to view the past year as not good economically (51%). While this majority grows even larger among the centrist and left-wing cohorts. Arab Israelis give the past year’s economic situation a much lower rating than do Jewish Israelis.

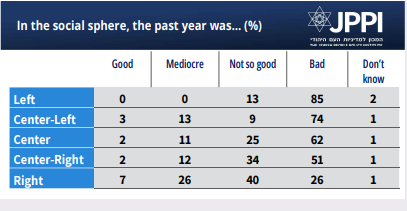

Regarding the social sphere, there is relative consensus. There is almost no difference in responses between Jews and Arabs. Although disparities exist between Jewish cohorts according to ideological orientation, a majority in all cohorts feel that the past year was either “not good” or “bad” in terms of social issues.

Data for JPPI’s September Israeli Society Index was collected between August 31 and September 6, 2025. The survey was administered to 788 Israeli respondents, Jews and Arabs. Data was collected by theMadad.com (580 Jewish sector respondents in an online survey) and Afkar Research (202 Arab sector respondents, about half online and half by phone). The data was weighted and analyzed according to voting patterns and religiosity to represent the adult population of Israel. The Index is compiled by Shmuel Rosner and Noah Slepkov. Professor David Steinberg serves as statistical consultant.