The report contains several parts pertaining to beliefs, the observance of traditions, and changes in attitudes – emphasizing youth up to age 25 – in the wake of the war.

Findings:

- Many Israelis report increased observance of tradition since the onset of the war.

- Among secular Jews – the largest group in Israel – there is evidence of a decline in tradition observance.

- The reported strengthening in tradition-observance is concentrated among the “traditionalist” (Masorti), religious (Dati), and ultra‑Orthodox (Haredi) groups.

- The claim of increased traditional observance is especially evident among young (25 or under) Jews.

- A quarter of Jewish Israelis say they are more tradition-observant than in the past; the share is higher among young people.

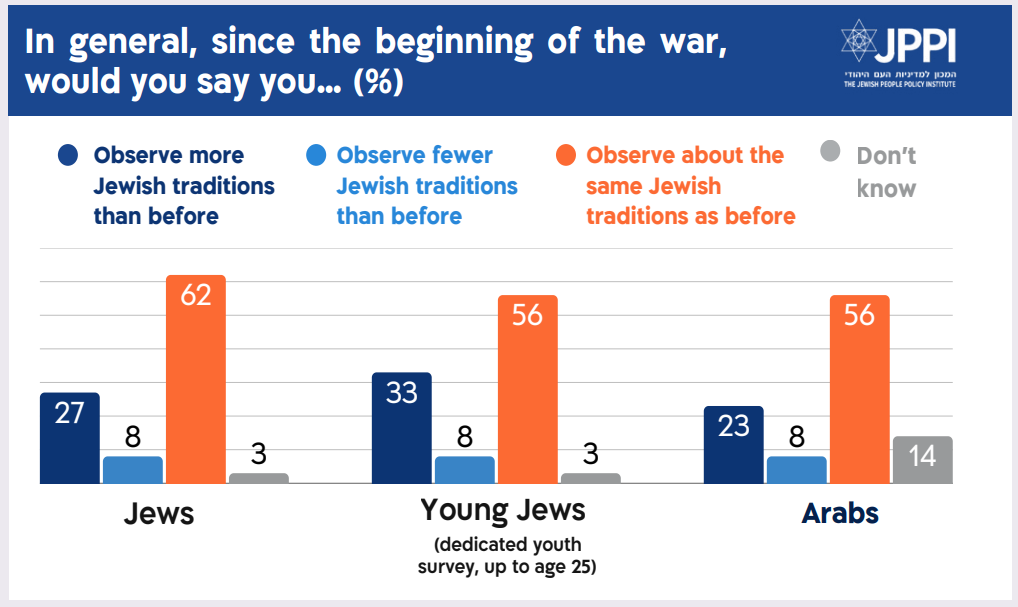

- Arab Israelis also report heightened observance of religious traditions since the onset of the war.

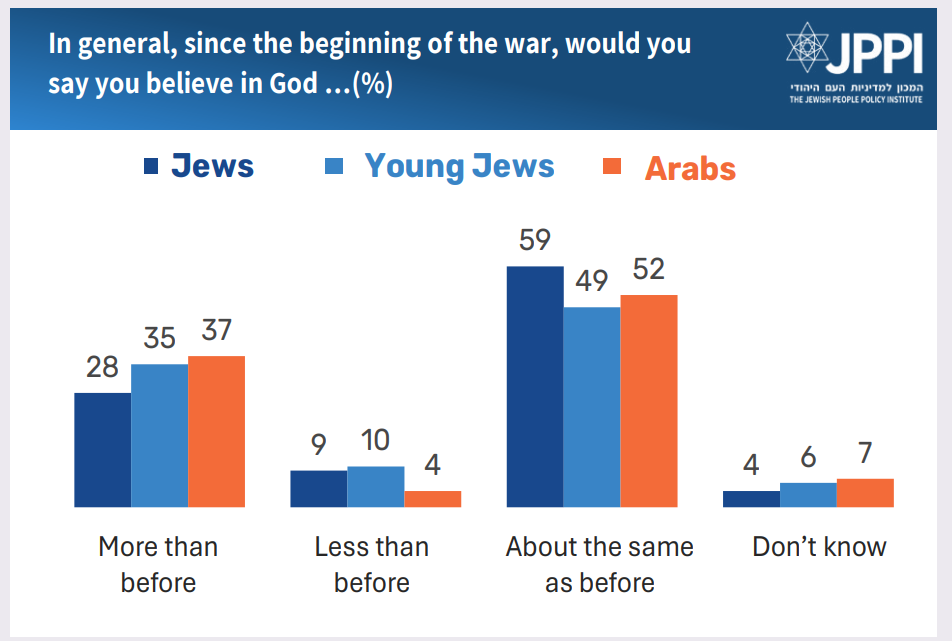

- Jewish and Arab Israelis alike say their belief in God has strengthened.

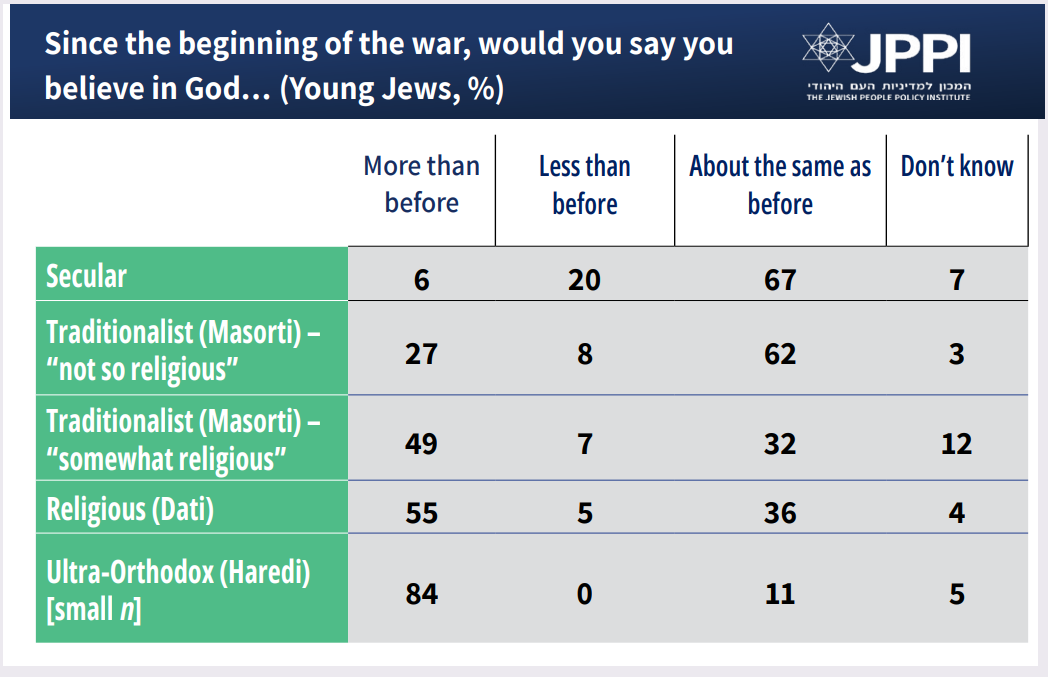

- Strengthened belief in God is evident among the traditionalist (Masorti), religious (Dati), and ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) groups; there has been a decline in belief among secular Jews.

- A rightward shift is observable among the Jewish public over the course of the war; no such change is observable among the Arab public.

To download the PDF file, click here.

In recent months, Israeli public discourse has featured an ongoing debate about the war’s impact on the observance of tradition in Israel. Much of this discussion has focused on visible, attention‑grabbing phenomena: students in state schools putting on tefillin – and the controversies this has sparked; the popularity of songs referencing Jewish tradition and faith; joint prayers among soldiers; and the wearing of emblems that display belief or tradition (such as a “Messiah” patch). Alongside these reports, several surveys have examined questions concerning traditional observance in Israel; their findings have, to some extent, validated the claim of a “strengthening” in traditional observance. (The term “strengthening” is, of course, ideologically loaded; we do not use it as a value judgment about the positive or negative character of changes in the public’s traditional practices.)

With the conclusion of the war, JPPI conducted a dedicated survey to examine several aspects of this phenomenon. The survey assessed beliefs, practices, and attitudes among Jewish and Arab Israelis, with particular emphasis on the attitudes of young Jews – the “soldiers’ generation,” to whom a large share of public reporting has referred. This report calls for caution for two reasons. First, the war has only just ended; it is premature to say whether what we observe now has long‑term implications or is primarily a short‑term response to a turbulent period that may fade with time. Second, many questions rely on respondents’ assessments of their current state relative to their prior state; it is possible that what they report about the past reflects a desire to highlight a contrast, even if, in practice, little has changed. Of course, the very desire to present a change is meaningful, as it reflects a significant sentiment (“I want to think that today I believe more/less than I did before”).

As noted, a principal finding is that there is indeed an overall rise in traditionalism across some Israeli social sectors. The increase is mainly discernible among those who already saw themselves, at least to some degree, as traditional or religious to begin with, and is not found among secular Jews. In fact, among secular Jews – who constitute the largest segment of the Jewish Israeli public (about four in ten) – there has been a decline in traditionalism in the war’s wake.

Observance of Traditions

According to the self-reporting of Israelis, the war period brought change in their habits of traditional observance across several domains. For many, this change has taken the form of more frequent performance of religious customs (or at least the feeling that they are doing so more often).

In response to a general question about traditional observance, most Jewish Israelis (62%) report that they observe Jewish tradition to the same extent as before, while 27% note an increased observance, and 8% report a decrease. Overall, then, there is a net increase in observance of customs – a trend that is even more pronounced among Jews under 25: one‑third (33%) say they observe more tradition than in the past. Among Arab Israelis, about a quarter (23%) report strengthened observance of traditional customs during the war. In other words, there has been an increase of roughly one‑fifth to one‑quarter in traditional observance among both Jews and Arabs in Israel.

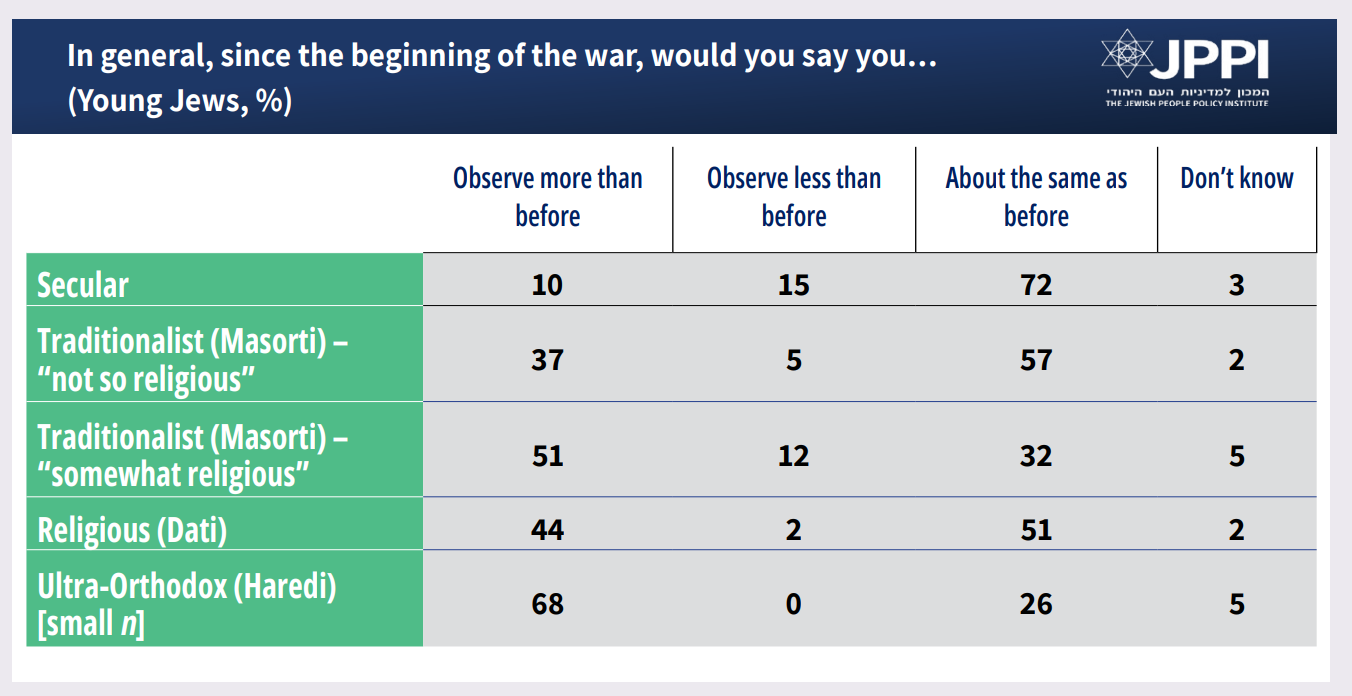

Again, it must be emphasized that the reported uptick in Jewish traditional observance is mainly among those who initially identified themselves as at least somewhat traditional or as religious. JPPI’s survey differentiates five population groups among Jewish Israelis, as defined by Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). The largest group is secular Jews (about four in ten Jews). There are then two “traditionalist” (Masorti) groups – “traditionalist, not so religious” (about one‑fifth of all Jews) and “traditionalist, somewhat religious” (about one‑tenth of the Jewish public). The more religious a respondent’s identity, the higher the share who report observing more traditional customs.

While fewer than one in ten secular Jews said they had increased the intensity of ritual observance – and nearly 15% say they had reduced it (yielding a slight overall decline in observance among secular Jews) – every other group reports an increase. In other words, the war strengthened traditional attachment primarily among populations already inclined toward a traditional or religious identity. Among religious (Dati) and ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) respondents, the change reflects greater adherence to their practices before the war– or at least a feeling of greater adherence. The most discernible change is found among Traditionalists – especially the “not so religious” among them.

Among Jewish Israelis aged 25 or under, the pattern is even more pronounced. Among the secular, there is a slight net decline (5%) in observance. Among non‑religious traditionalist youth, there is a very substantial net rise – about one‑third of this respondent cohort. Among somewhat‑religious traditional youth, the net increase is about 40 percentage points. A Rushinek Institute survey from a few months ago found a similar pattern on “drawing closer to” or “moving away from” religion: 22% reported drawing closer (35% among the young), and 13% reported “moving away.”

Moving from a general question about observance to specific practices, we asked respondents whether they are now doing the following more than before the war: about one‑third of Jews (31%) report praying more since the war began, and one‑fifth (20%) report reading the Bible (Tanakh) or Psalms (Tehillim) more. One in ten reports going to synagogue more often (11%), lighting Shabbat candles more frequently (11%), wrapping phylacteries (tefillin) more often (9%) or dressing more modestly (9%). Among young Jews, the degree of “strengthening” is greater: 38% pray more and one‑quarter (26%) read the Bible more; 14% of young Jews report going to synagogue more, lighting Shabbat candles more frequently and dressing more modestly. Among Arab Israelis, the trend is similar: more prayer (32%), greater modesty (12%), and increased church/mosque attendance (10%). Put differently, the war led many Israelis – especially the young – to turn more avidly toward faith and religious expressions of identity, or at least to feel that they have done so. (In the Rushinek survey noted earlier, regular and occasional synagogue attendance rates found no significant change compared with CBS data from over a decade ago; thus, “I go to synagogue more” does not necessarily indicate a measurable increase in actual attendance.)

As in the previous question, young Jews differ by their baseline religious identity. Among secular youth, a large majority (84%) say they have not added traditional practices since the war; only a small minority (7%) report praying more. Moving from the secular to the traditionalist categories, the reported change grows: among non‑religious traditionalist (Masorti) youth, almost half (43%) report change – especially more prayer (42%), more Bible/Psalms reading (23%), and more Shabbat candle‑lighting (20%). Among somewhat‑religious traditionalist and religious (Dati) youth, the share reporting increased observance is even higher: more than half say they pray more, and about 42% read the Bible/Psalms more.

Belief in God

Estimates of the share of Israelis who believe in God vary according to question wording, but among Jewish Israelis, this share has long stood at roughly 70-80%. Several surveys indicate that the overall share of believers did not change due to the war: a Reichman University survey (July 2025) found that 78% of all Israelis believe in God; a Pew Research Center survey two months earlier found 74%. These figures do not reflect any increase compared with the pre‑war period.

In this JPPI Israeli Society Index survey, we did not measure the level of belief directly; instead, we asked whether respondents felt that their belief had changed because of the war. Again, this is a question about perceived change rather than an objective measure of actual change. A quarter of Jewish (28%) and 37% of Arab respondents say their belief in God has strengthened, while far smaller shares report a decline in belief – 9% of Jews and 4% of Arabs. Among young Jews, the war’s impact on belief is greater than in the overall Jewish population: 35% say they believe in God more than before, 10% say they believe in God less than before; and 49% say their level of belief is about the same as before.

Here too, the reported change is stronger as one moves along the religious spectrum from secular to religious. Among secular youth, 6% report an increased belief in God, and 20% report a decline (among secular Jews of all ages, 5% report increased belief, and 16% report a decrease). Thus, among secular youth, the share of those believing in God declined – at least as respondents perceive it. The share reporting a decline diminishes steadily as we move toward more religious groups. Among non‑religious traditionalist youth, the net increase in belief is about 20 percentage points; among somewhat‑religious traditionalist youth, more than 40 percentage points; and so on. In most cases outside the secular cohort, the change reflects a strengthened belief in God among those who already believed rather than a shift from non‑belief to belief.

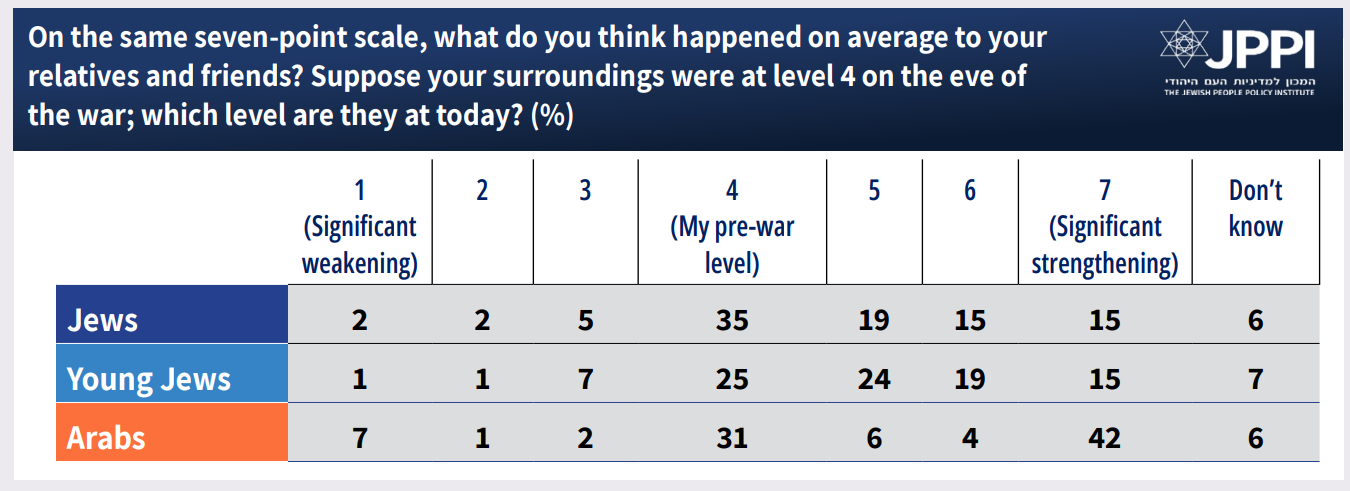

In a differently worded question, respondents rated how much their belief had strengthened or weakened on a seven‑point scale, where 4 represented their pre‑war belief; respondents could move up or down the scale (or remain at 4 if there was no change). The largest share of Jewish respondents (43%) reported no change (remaining at 4). An identical share (43%) reported strengthening (levels 5–7), while 12% reported weakening (levels 1–3). Among young Jewish Israelis, the strengthening pattern is similar but more pronounced: the share choosing levels 5–7 is higher than in the overall Jewish population. Among Arab respondents, a substantial strengthening is evident – half (52%) report a stronger belief, 42% say it is an especially marked strengthening (42%), while only a small minority (10%) report a weakened belief.

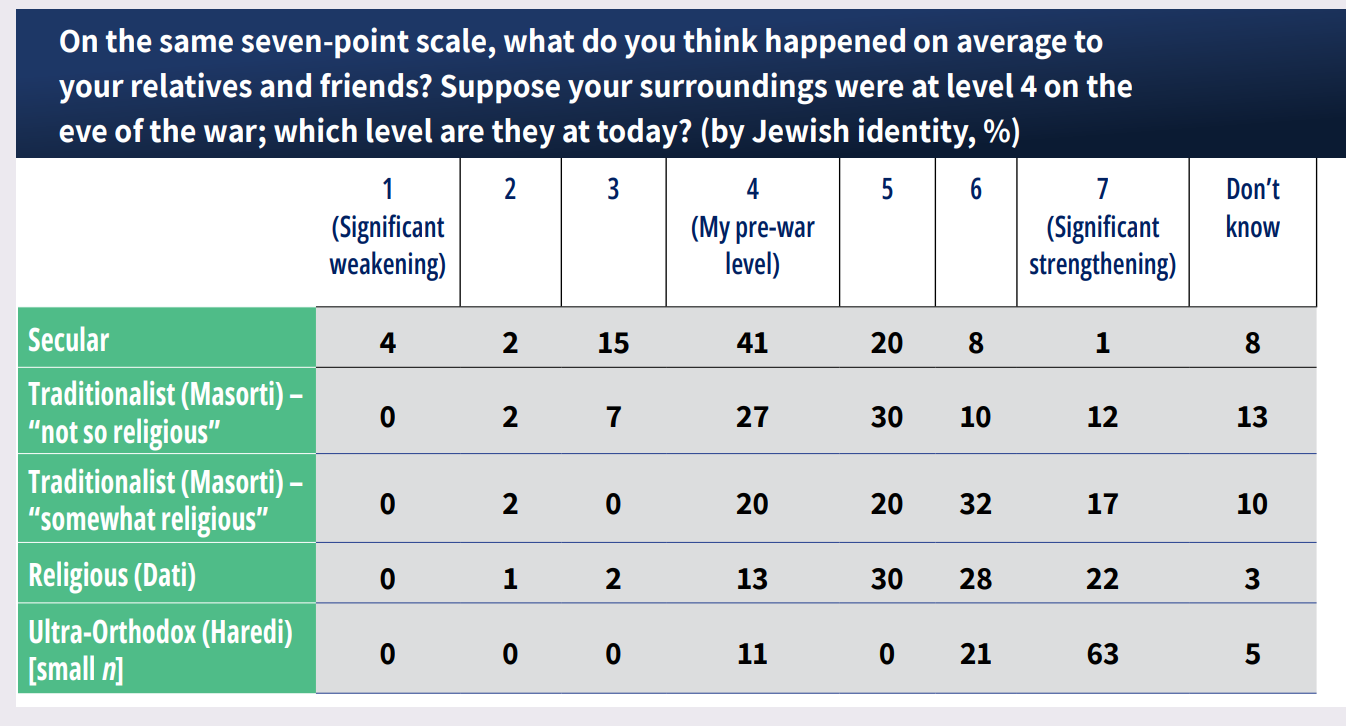

Here again, the difference between secular respondents and respondents in every. A majority (56%) of secular Jews report no change; a quarter (25%) report weakening; and 15% report strengthening – thus, overall, more weakening than strengthening. Among non‑religious traditionalist Jews there is a clear tendency toward strengthening: half (50%) report some increase, while only a small minority reporting a decline. Among somewhat‑religious traditionalists and religious Jews, about seven in ten report an increase. This is also the case for the ultra-Orthodox cohort (whose subsample [n] in the youth survey was intentionally small; any inference must therefore be made cautiously).

We then asked respondents to estimate what, in their view, happened to the belief of those around them.Half (49%) of Jewish Israelis believe that friends and relatives have strengthened their belief to some degree; one‑third (35%) think it has stayed the same; and only a small minority (9%) think belief has weakened. Among young Jews, the perception of change is even stronger: 58% perceive a strengthening in belief, and one‑quarter (25%) think the belief of those around them has remained unchanged. Half (52%) of Arab Israelis think the belief of those around them has strengthened; 42% say significantly (42%).

Interestingly, secular Jews join the other groups in perceiving a strengthening of belief: nearly one‑third (29%) report that the belief of “friends and relatives” has strengthened, while about one‑fifth (21%) perceive a weakening – even though, as we saw earlier, the self‑assessment among the secular cohort shows a clear tendency toward weakening belief. The perception of strengthened belief among one’s friends and relatives rises as one moves from secular toward traditionalist (Masorti) and religious (Dati) identities. Among non‑religious traditionalist Jews, half (52%) perceive a strengthening; among somewhat‑religious traditionalist and religious Jews, the pattern is even more pronounced, with many choosing the higher levels on the scale.

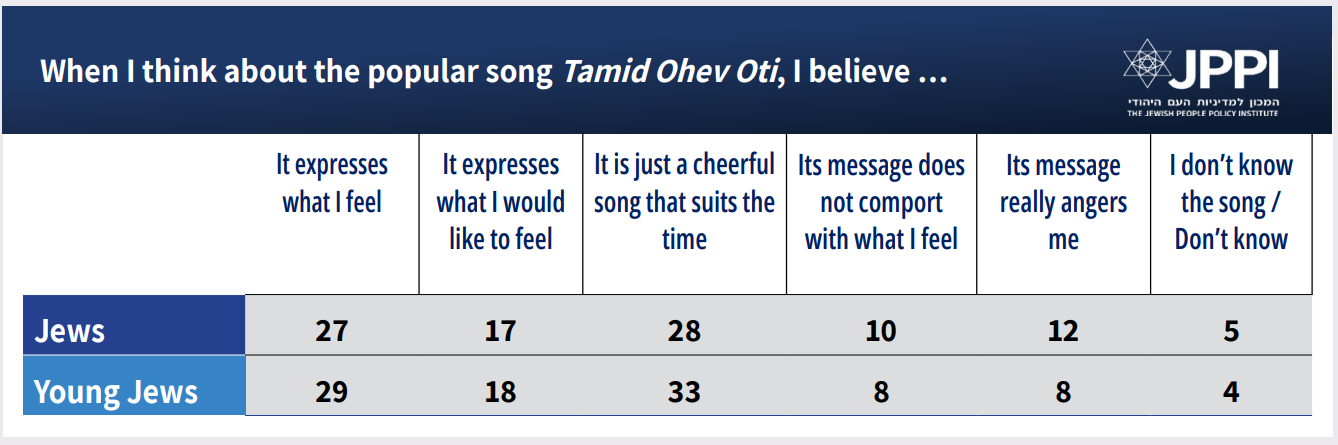

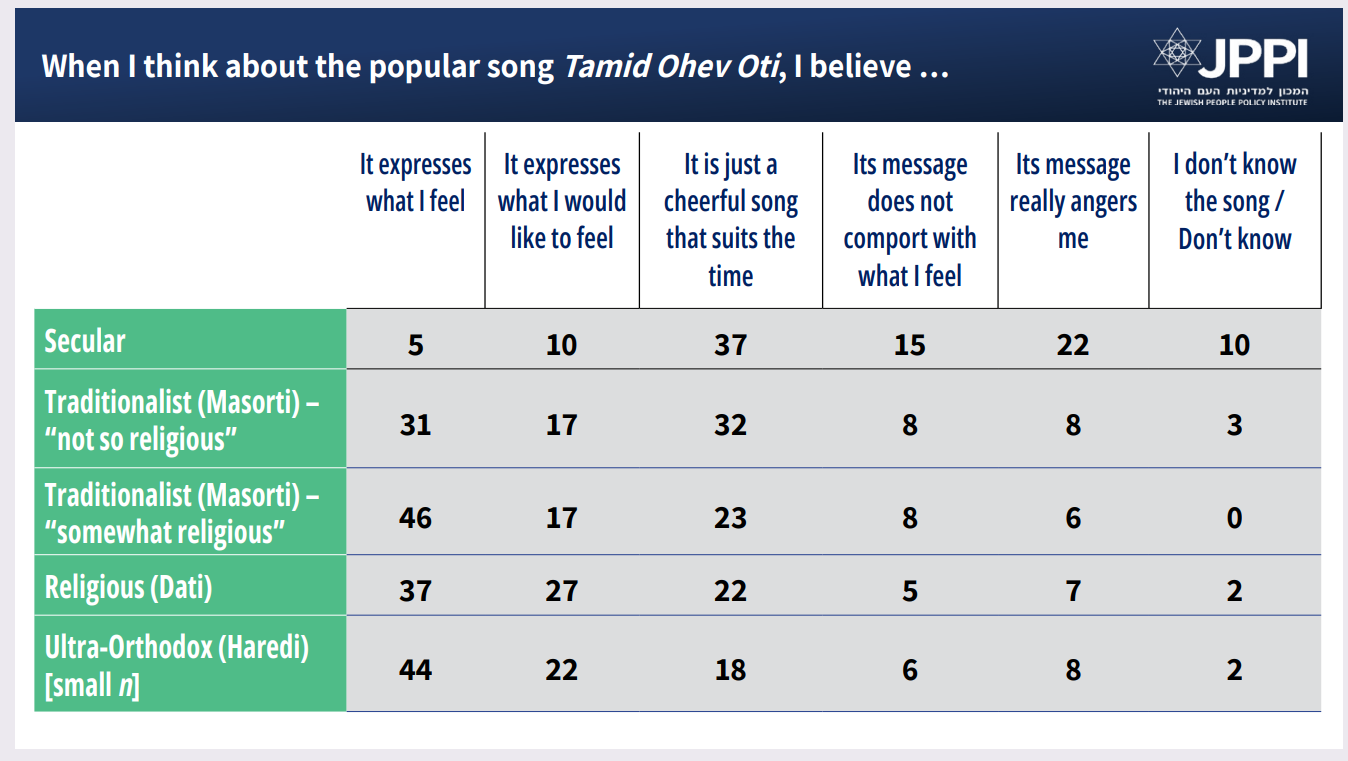

To examine the cultural element in public discourse regarding “belief strengthening,” we included a question about the hit song Tamid Ohev Oti ([God] “Always Loves Me”) by Sasson Shaulov, which has been played widely in many contexts and has more than 42 million views on YouTube (see English translation of the lyrics here). A quarter (27%) of Jewish respondents say the song expresses their personal feelings; about one‑fifth (17%) see it as expressing what they would like to feel. Another quarter (28%) regard it mainly as a cheerful song that fits the time. Conversely, about a fifth (22%) believe that the song’s message does not fit what they feel or even angers them. Among young Jews, there is a slightly higher tendency to identify with the song (29%) and to regard it as a cheerful song (33%), with lower rates of rejection or opposition to its message.

Attitudes toward the song vary substantially between the secular Jewish cohort and all other Jewish cohorts. Among secular Jews, more than one‑third (37%) say the song does not suit them or angers them; only 15% say it expresses what they feel or would like to feel. In all other groups, a majority of respondents say the song expresses what they feel or would like to feel. Notably, very few Jewish Israelis say they do not know the song.

Self‑Definition

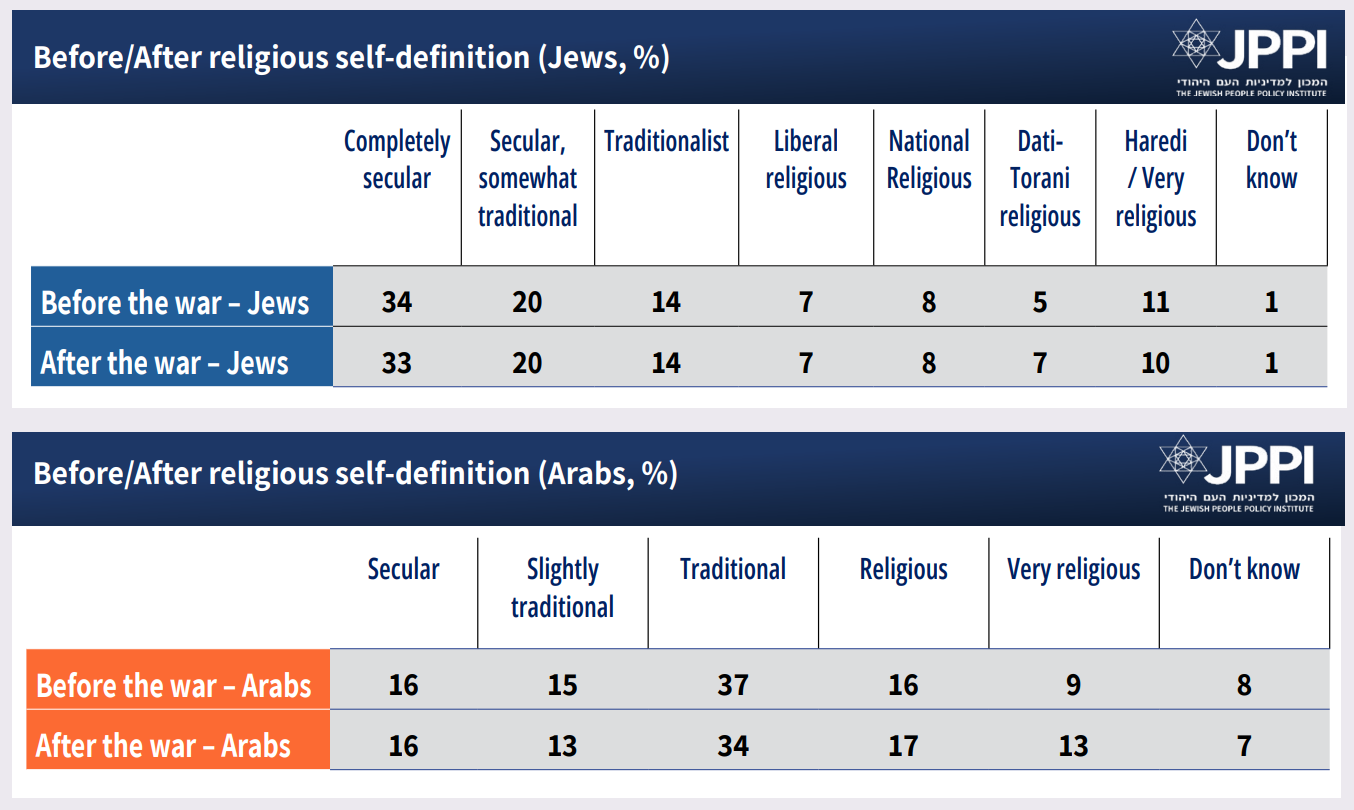

Alongside the standard CBS five‑category religious scale, we asked Jewish respondents to rate themselves on a more specific seven‑category scale used in previous JPPI research on Israeli Judaism. We asked them to do so twice: how they self-identified before the war, and how they define themselves today. Overall (in the full sample), only minimal shifts were found between the “before” and “after” definitions. For example, 34% said they were “completely secular” before the war, versus 33% who say they are “completely secular” today. As the table shows, the other categories are likewise nearly unchanged. Among Arabs – who were presented with a five‑category scale (secular, slightly traditional, traditional, religious, very religious) – there is a slight trend toward increased religiosity, but still by only a few percentage points: the “very religious” rose from 9% to 13%, while the “traditional” fell from 37% to 34%.

When examined via a transition matrix, internal movements within each Jewish religious group can be seen. (Caution: movements within smaller groups should be weighted lightly.) Most Jewish Israelis report stability in their place on the traditionalism scale since the war’s outbreak. Of those who were “completely secular” before the war, 91% remain so; 6% now define themselves as “secular, slightly traditional,” and only very small shares moved to other categories. Among the “secular, slightly traditional,” 81% stayed in the same category, while about one in ten (11%) moved to “traditional,” and one in twenty now define themselves as “completely secular.”

Among young Jewish respondents, somewhat larger movements are visible than among all Jewish adults – perhaps because younger people are still forming their identities, and perhaps because the war’s impact has been stronger in this cohort. The most notable shifts are among those who pre‑war identified as “traditionalist” or as “liberal religious.” Among the “completely secular,” a large majority (86%) remained in that category, but 10% now identify as “secular, slightly traditional.” Among the “secular, slightly traditional,” a meaningful shift occurred toward more traditional categories: 14% now identify as “traditionalist,” and 3% as “liberal religious.” Among the “traditionalists,” a fifth (19%) moved to “liberal religious” and a tenth (10%) to “Torani-dati.”

Political Self‑Identification

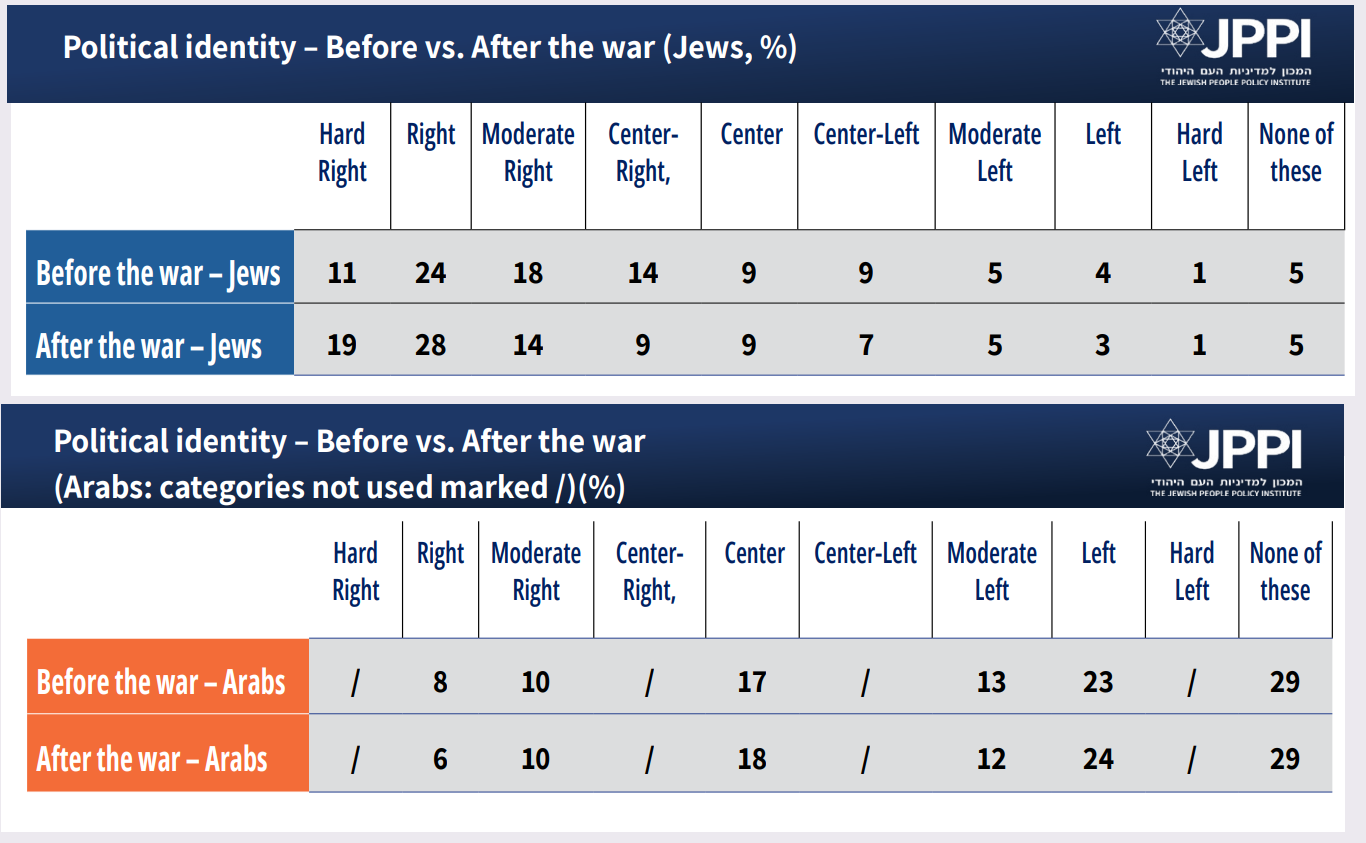

We also asked about changes in political self‑placement on a nine‑point scale (five‑point scale among Arabs). According to Jewish respondents’ self‑assessments, since the war’s outbreak there has been a clear rightward shift. Among Arabs, there is stability.

Among Jewish Israelis, the largest overall group identifies with the right in its various shades. Within this group, the more strongly right‑wing categories grew, while the categories closer to the center shrank. Specifically, among all Jewish respondents, “hard right” rose from 11% to 19%, and “right” rose from 24% to 28%. Conversely, “moderate right” and “center-right” fell (from 18% to 14%, and from 14% to 9%, respectively). There were also slight declines in the center and the left. (Again, movements in very small cohorts – such as “hard left” – cannot carry statistical weight.) Among Arabs, nearly no changes appear: the center, left, and right maintained their pre-war share distribution.

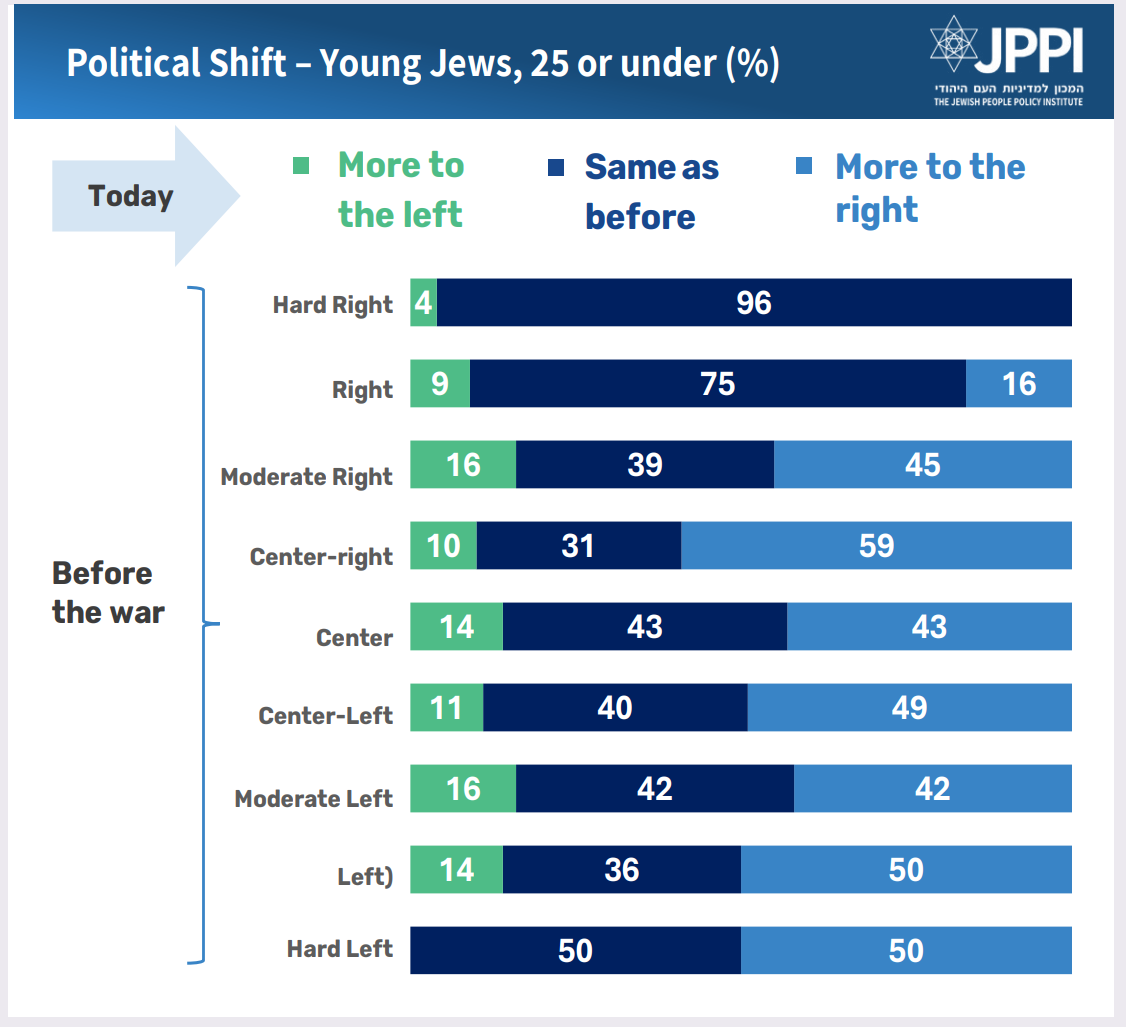

The rightward shift is also evident among young Jews, in almost every pre-war political group. Nearly half (45%) of those who say they were “moderate right” before the war – and a majority (59%) of those who were “center-right” – report moving further right. Even among those who identified as “center” or “moderate left,” substantial shares report a rightward move – 43% of centrists and 49% of those “center-left.” Among those who identified as “left” or “hard left,” about half (50%) report a move rightward. Overall, the data shows a broad rightward movement among young Jews across the political spectrum, including those who previously identified with the center and left.

This special JPPI survey was administered between October 30 and November 3, 2025 to 1,257 respondents. Data was collected by theMadad.com (552 Jewish sector respondents in an online survey), Afkar Research (205 Arab sector respondents, about half online and half by phone), and Migdam Research & Consulting (~ 500 non-Haredi Jewish respondents aged 18-25, online). The data was weighted and analyzed according to voting patterns and religiosity to represent the adult population of Israel. JPPI’s Israeli Society Index is compiled by Shmuel Rosner and Noah Slepkov. Yael Levinovsky provides research, writing, and production assistance. David Steinberg serves as statistical consultant.