The Iranian Threat, Trust in Leadership and the Army, US–Israel Relations, Separation in the Public Sphere, and Perceptions of Zionism, Racism, and Antisemitism.

Additional Findings:

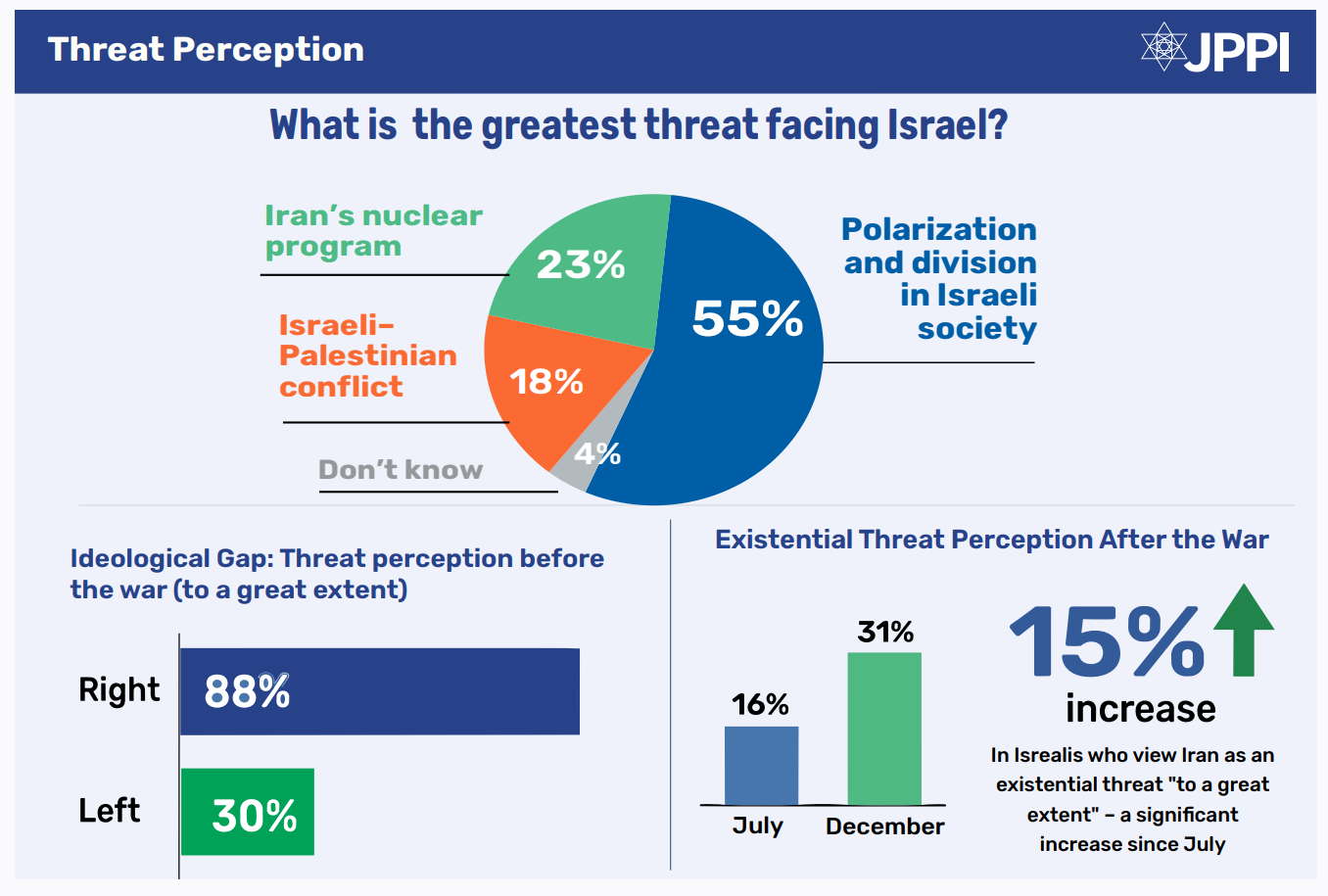

- Most Israelis see Iran as an existential threat; half of Arab respondents believe the threat is small or nonexistent.

- Perception of the Iranian threat increases the further one moves to the political right.

- Most of the public thinks social polarization is Israel’s greatest danger, more than the Iranian threat.

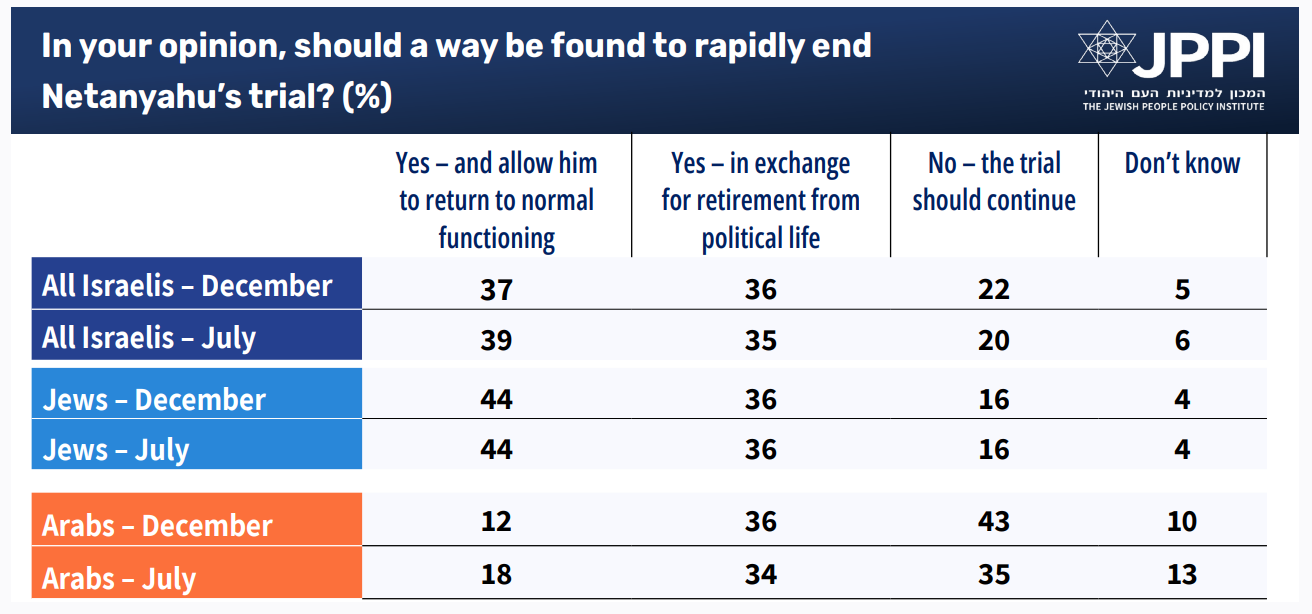

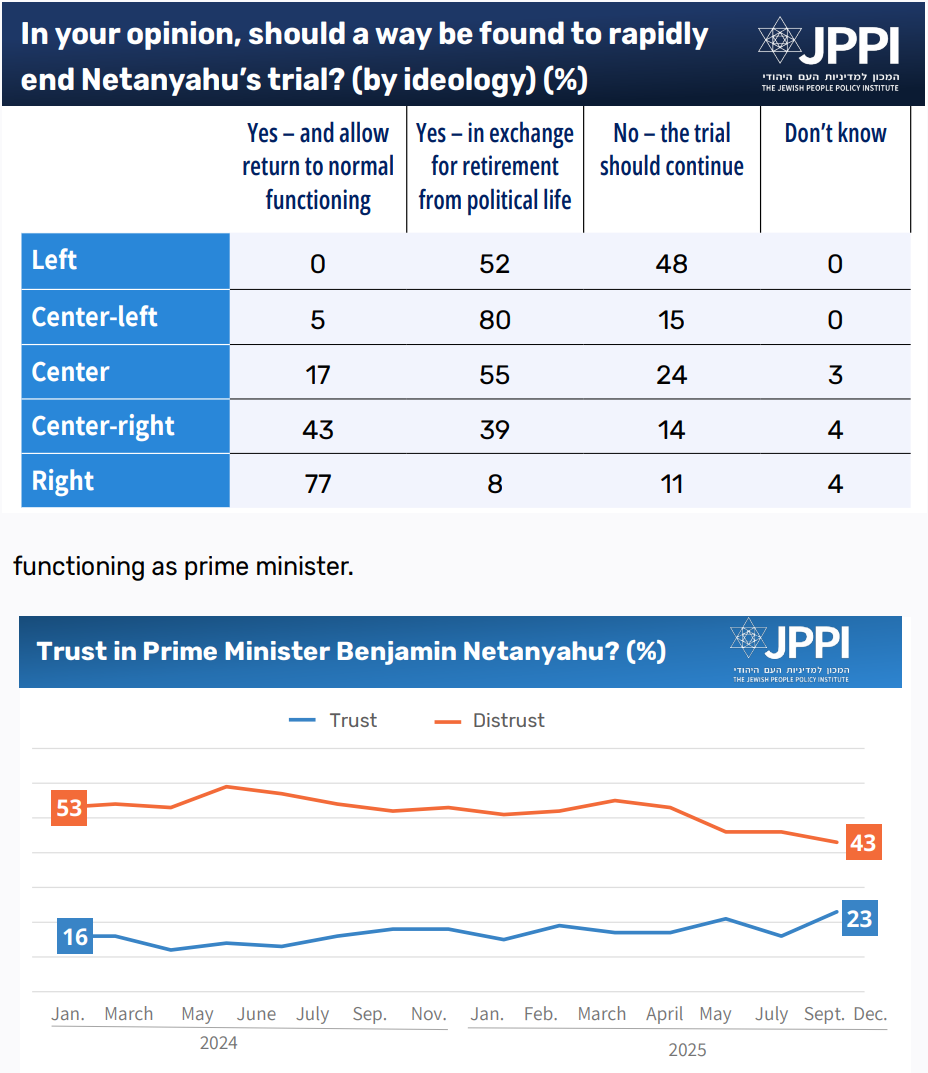

- Most Israelis support shortening Netanyahu’s trial – half of them only in exchange for his retirement from political life.

- The center-left opposes a pardon without Netanyahu’s retirement; the right supports his full return to office.

- There has been a slight increase in the share of Israelis who “strongly trust” the prime minister – a peak since early 2024.

- There has been a significant increase in the share of Arab Israelis who report trusting the IDF.

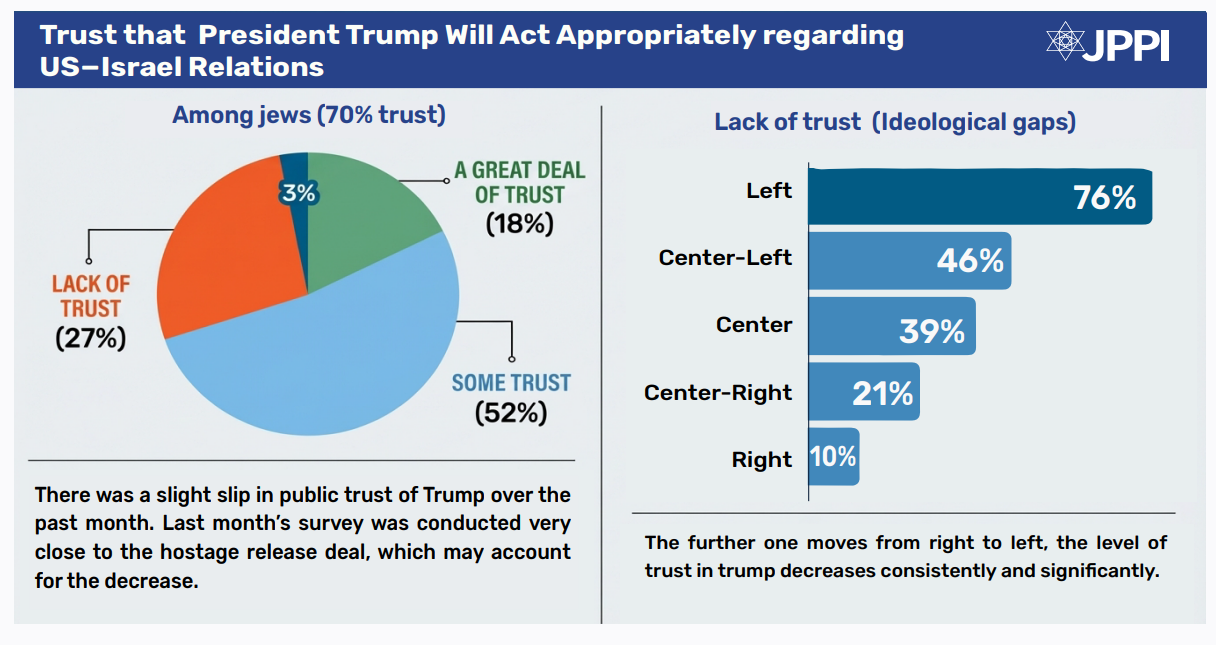

- Even in light of disagreements, most respondents express confidence that Trump will do the right thing regarding Israel.

- The share of Israelis who think Israel must make a major effort to preserve its alliance with the United States has significantly increased.

- Most Israelis, across all ideological groups, agree: Israel’s standing in the world is poor.

- Most Israelis say that Zionism is not racism, but a third believe that “some interpret it that way.”

- Most Arab Israelis believe that Zionism is racism or that it contains racist elements.

- Most Jewish Israelis link anti-Zionism and antisemitism, while their Arab counterparts believe that anti-Zionism and antisemitism are separate phenomena.

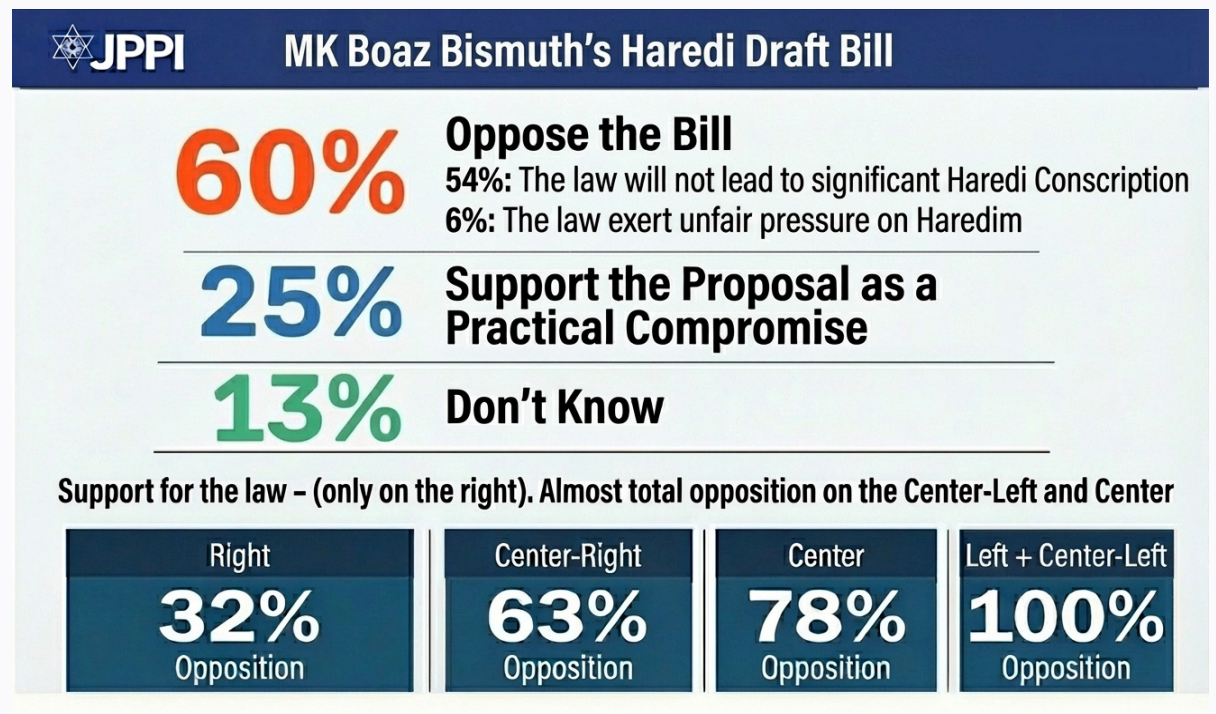

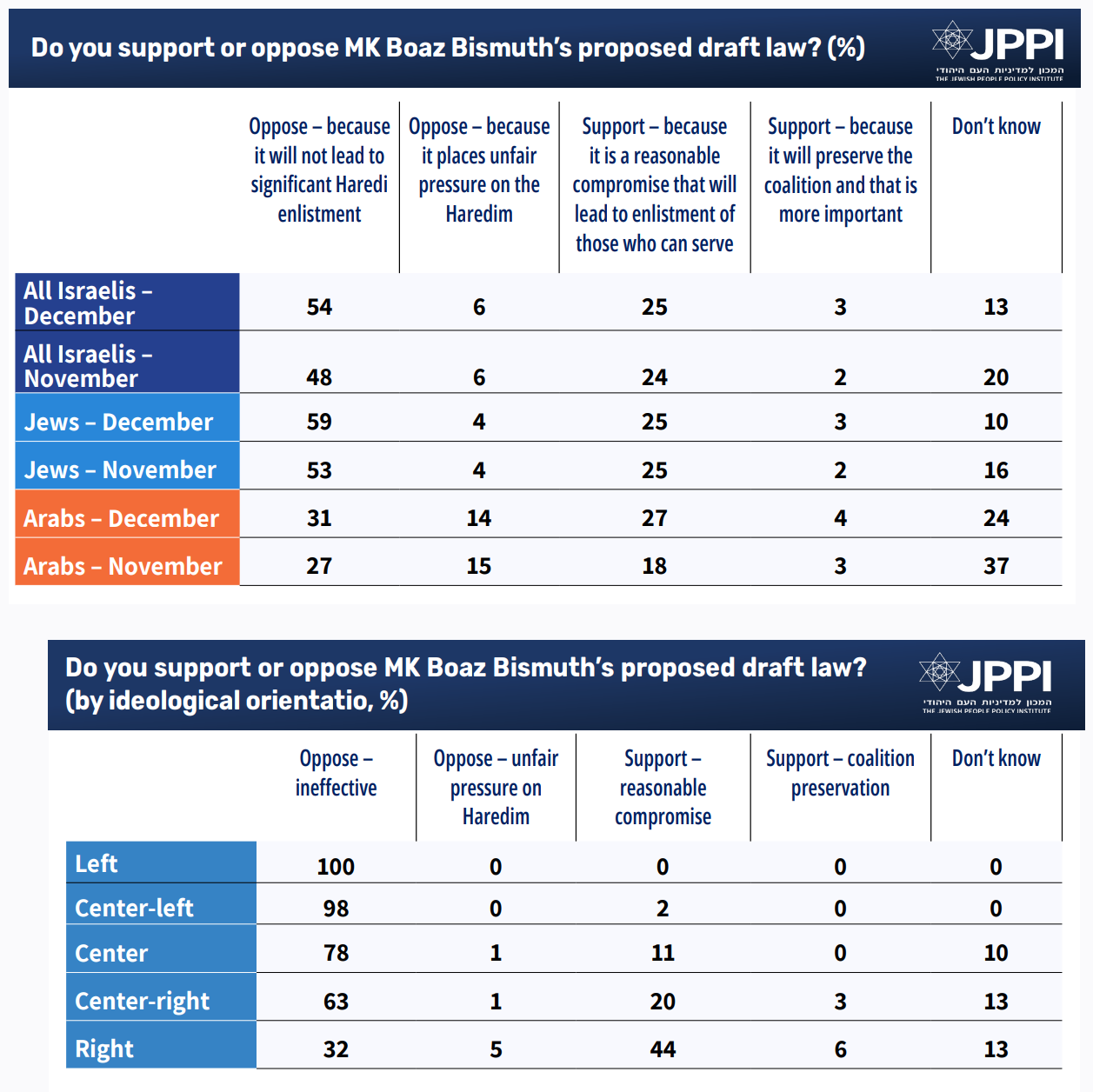

- Most Israelis oppose the Bismuth Haredi conscription bill; support for it grows as one moves rightward along the ideological spectrum.

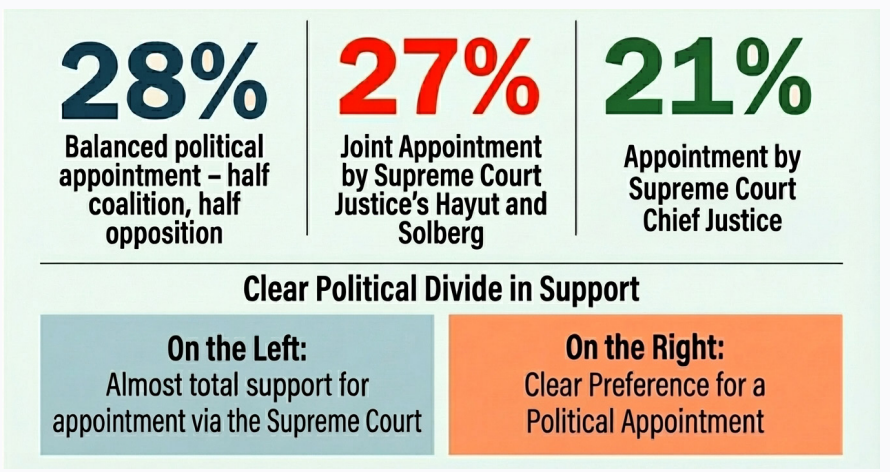

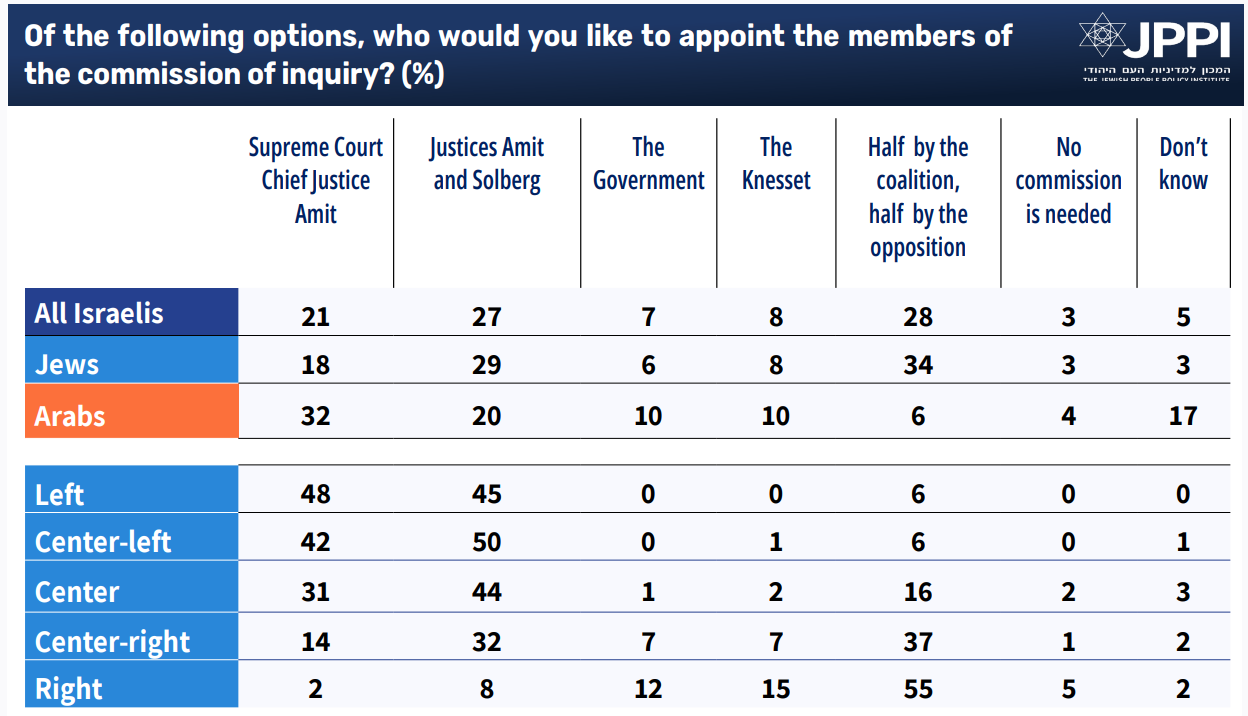

- Most prefer that members of a Commission of Inquiry into the lead-up to October 7 be appointed by the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

- Jews tend to explain violence in the Arab sector as a product of social factors; Arabs say that the problem originates with the state and its law-enforcement system.

- Most Israelis prefer public spaces shared by Jews and Arabs.

To download the PDF file, click here.

The Iranian Threat

The 12-day campaign against Iran ended six months ago. In this light, we again asked this month about Israel’s situation vis-à-vis Iran. The responses indicate that a significant share of Israelis have, after half a year, returned to baseline positions that see Iran as a major threat, even though many believe that the level of threat somewhat decreased after the campaign.

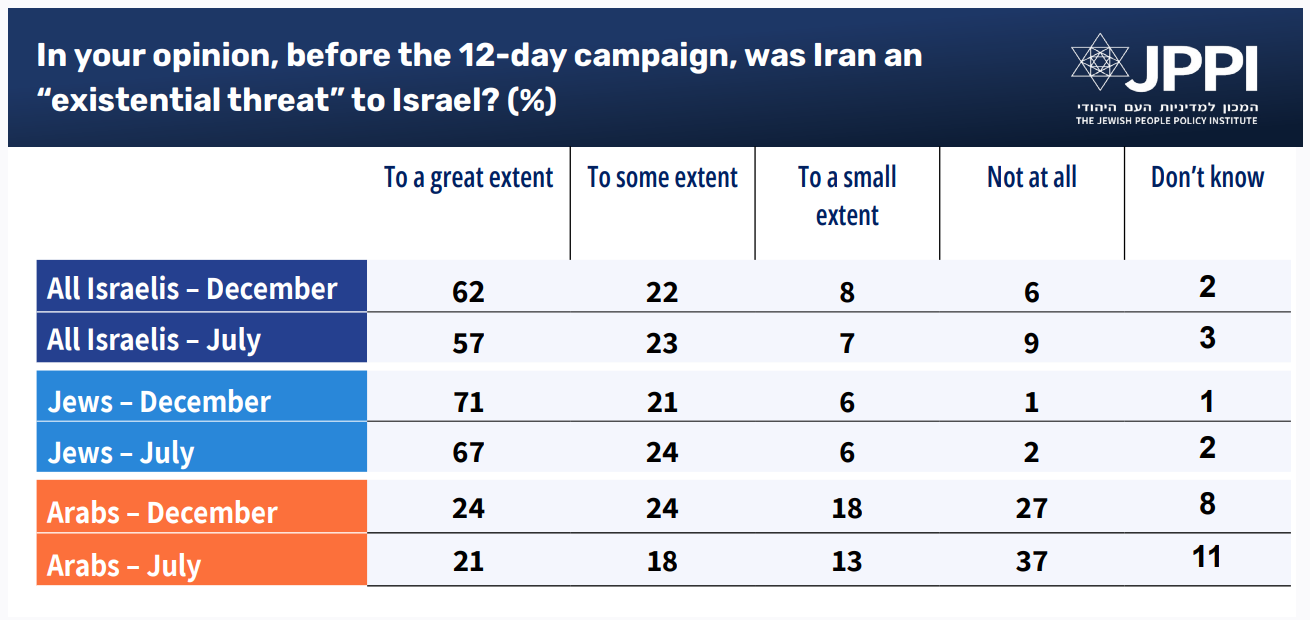

As in the July survey, conducted immediately after the campaign, we asked Israelis whether Iran was or was not an existential threat to Israel prior to the 12-day operation. Two-thirds of Israelis (62%) now believe that Iran was a great existential threat before the war, and another fifth (22%) assess that it constituted some threat. Only 14% believe the Iranian threat was small or nonexistent. Among Jewish Israelis, the share who view Iran as having been an existential threat is significantly higher than among Arab Israelis. About three-quarters (71%) of Jewish Israelis see Iran as having been a great existential threat, and only 7% think the threat was small or nonexistent. By contrast, among Arab Israelis, a quarter (24%) assess that Iran was a great existential threat, while another quarter (27%) believe it was not a threat at all.

Compared with data collected this past July, immediately after the campaign against Iran, there has been a slight increase (from 57% to 62%) in the share of Israelis who think Iran had been an existential threat prior to the campaign. This trend is evident among both Jewish and Arab Israelis. At the same time, there was a decline in the share of Arab respondents who believe Iran was not an existential threat to Israel at all (from 37% to 27%). Despite this decline, the Arab share holding this view is still much higher than among Jews.

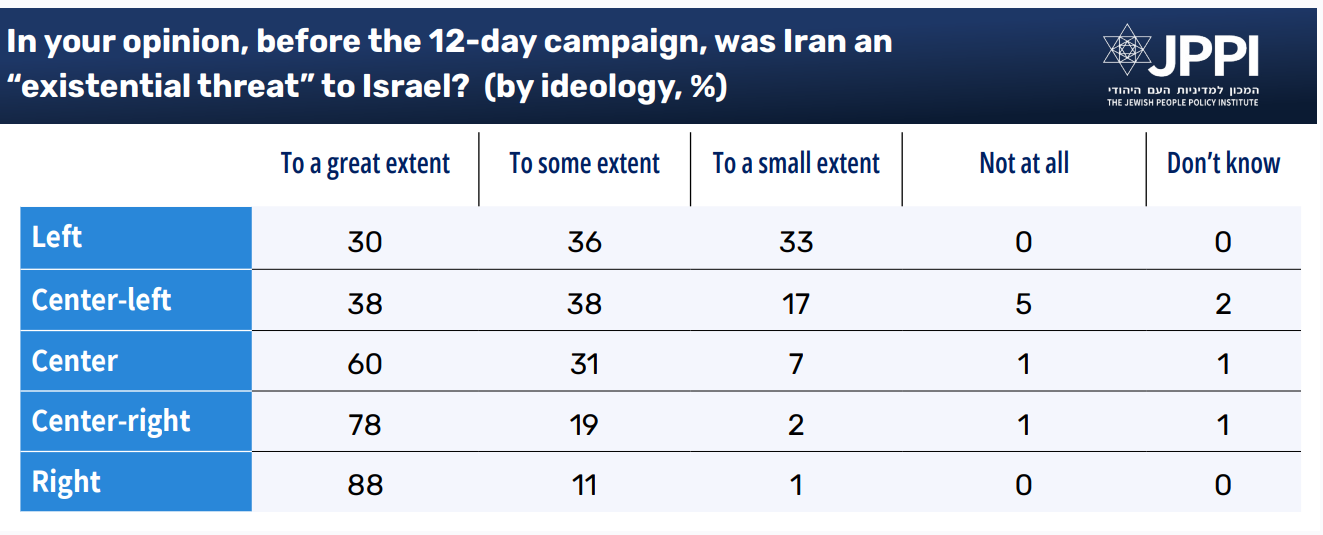

Broken down by ideological orientation, the perception of Iran as an “existential threat” prior to the campaign increases the further one moves rightward along the political spectrum. Among those identifying with the left, a third (30%) believe that Iran was a great existential threat, a third (36%) to some extent, and a third (33%) to a small extent. In the center-left group, threat assessment is also heterogeneous: the two leading assessments are that Iran was a great existential threat to Israel (38%) and to some extent (38%). From the center rightward, the perceived threat rises sharply: 60% in the center, 78% in the center-right, and 88% on the right think that Iran had been a great existential threat to Israel prior to the 12-day campaign.

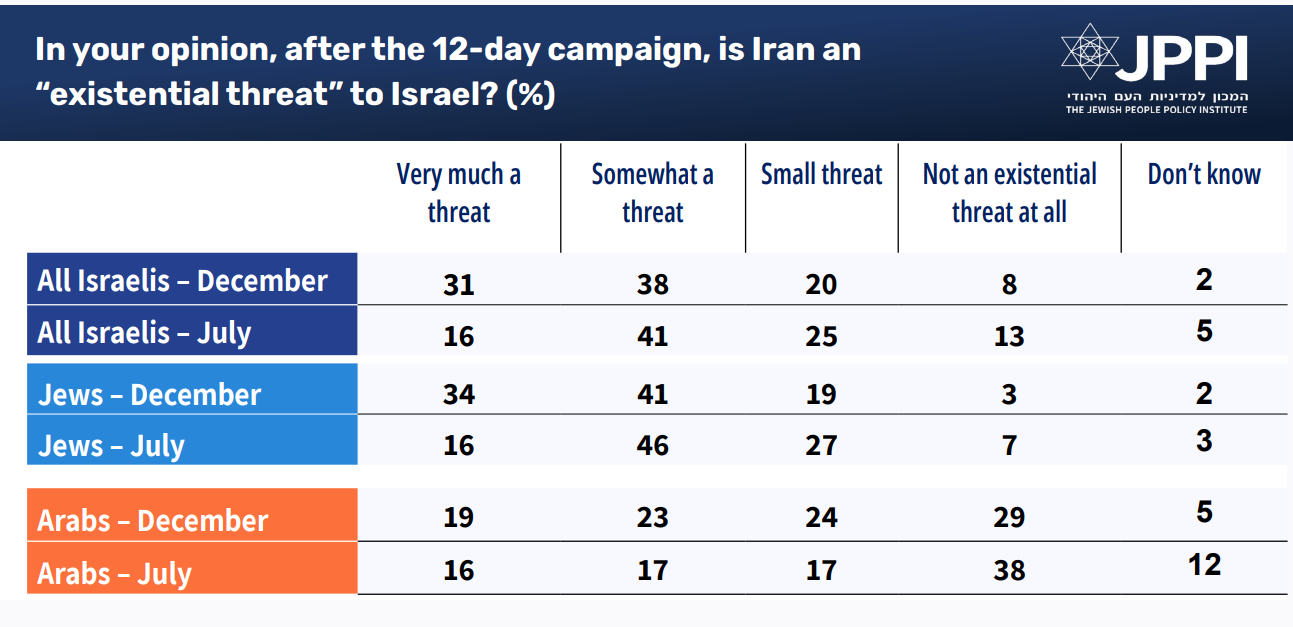

Half a year after the campaign, most Israelis still view Iran as an existential threat to Israel. On this question, however, we found a much larger change compared to July.

Today, a third (31%) of Israelis believe that Iran is a great existential threat, and another 38% see it as an existential threat “to some extent.” That is, a majority of the public thinks that the existential threat persists even after the campaign. A fifth (20%) of Israelis think that Iran constitutes only a small existential threat, and 8% believe that Iran does not constitute an existential threat to Israel at all. Among Jewish Israelis, the perceived level of threat is somewhat higher: 34% assess that a great existential threat still exists, 41% think it exists to some extent, and 3% believe that there is no threat at all. Among Arab Israelis, perceived threat levels are lower: half (53%) think that after the Iran campaign, the threat it poses is small or nonexistent.

Compared with the July data, there has been a substantial increase among Jews (from 16% to 34%) and Arabs (from 16% to 19%) in assessing that Iran poses a great existential threat to Israel. In other words, in July, immediately after the campaign, many Israelis believed that the level of the Iranian threat had dropped sharply (62% assessed that Iran was a significant threat before the campaign, but only 16% assessed it as a significant threat directly after the campaign). Now, the gap between perceived threat before and after the campaign has narrowed considerably. Still, a gap remains: 62% said that Iran was a significant threat before the campaign, versus 31% who say it is a significant threat today. Further, there is still a gap in the assessment of Iran as a major threat to Israel – in July it stood at 46 percentage points, when the impression of the campaign was still fresh, and now stands at 31 percentage points. At the same time, there has been a decline in the share who believe that Iran does not constitute an existential threat to Israel at all. Overall, the data reflects a rise in perceived threat, mainly among Jews, compared with the situation at the end of the campaign six months ago.

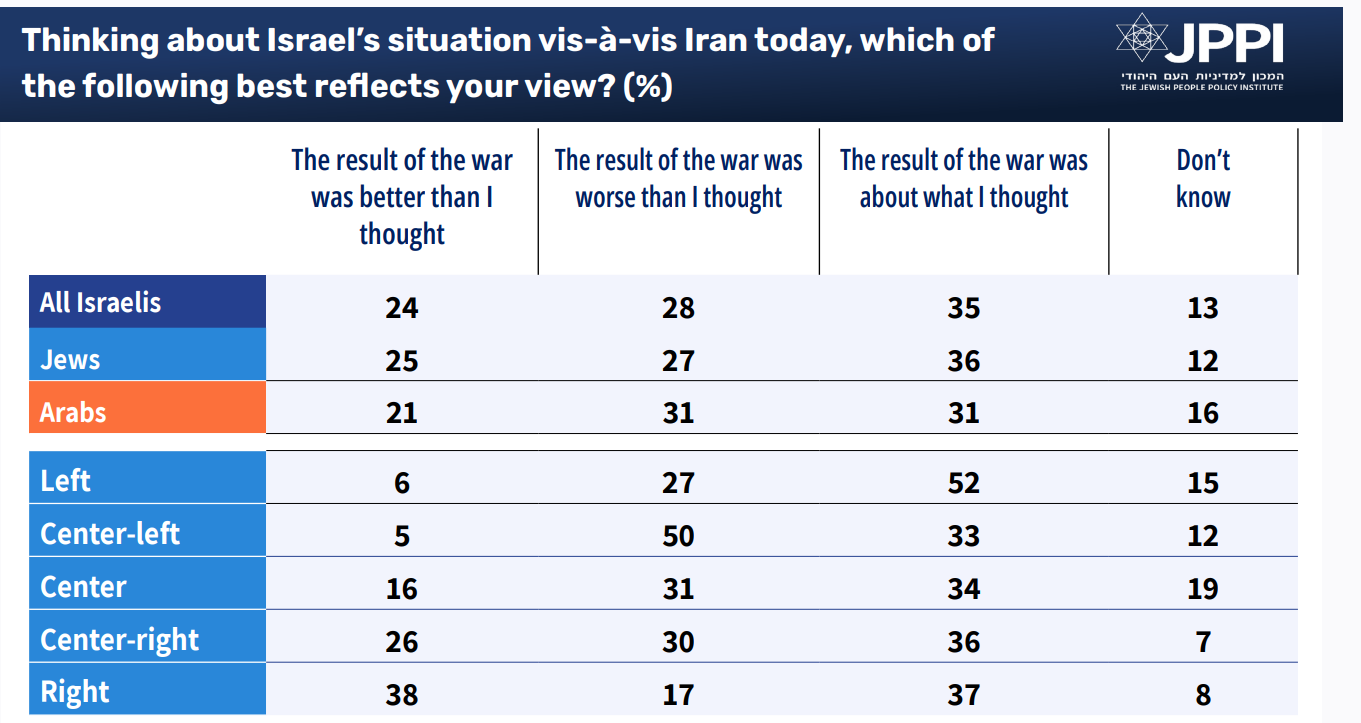

Alongside the comparison of identical questions in July and December, which – as we have seen – points to an erosion in the sense of achievement in Israel’s campaign against Iran (more Israelis have become convinced that the threat remained significant), we asked Israelis how they feel today, versus how they felt immediately after the campaign, about the outcome of the campaign against Iran.

A quarter (24%) of Israelis say that they now “understand” that the result of the campaign against Iran is better than they had thought just after it; a little more than a quarter (28%) think the result was worse than they had thought; and 35% say their current assessment is similar to what it was immediately after the campaign. Broken down by ideological orientation, only a small minority on the left and center-left now say that the war’s outcome was better than they thought, while a majority in these camps believe it was similar to, or worse than, what they had previously understood. On the right and center-right, the share is higher (38% and 26%, respectively) of those who think that the campaign’s outcome was better than expected. A similar pattern is evident in a breakdown by religiosity: moving from the secular toward the Haredi (ultra-Orthodox) end of the spectrum, the share of respondents who now say they see the war’s outcome as better than they had thought rises, and the share who think the outcome was worse than they had thought declines.

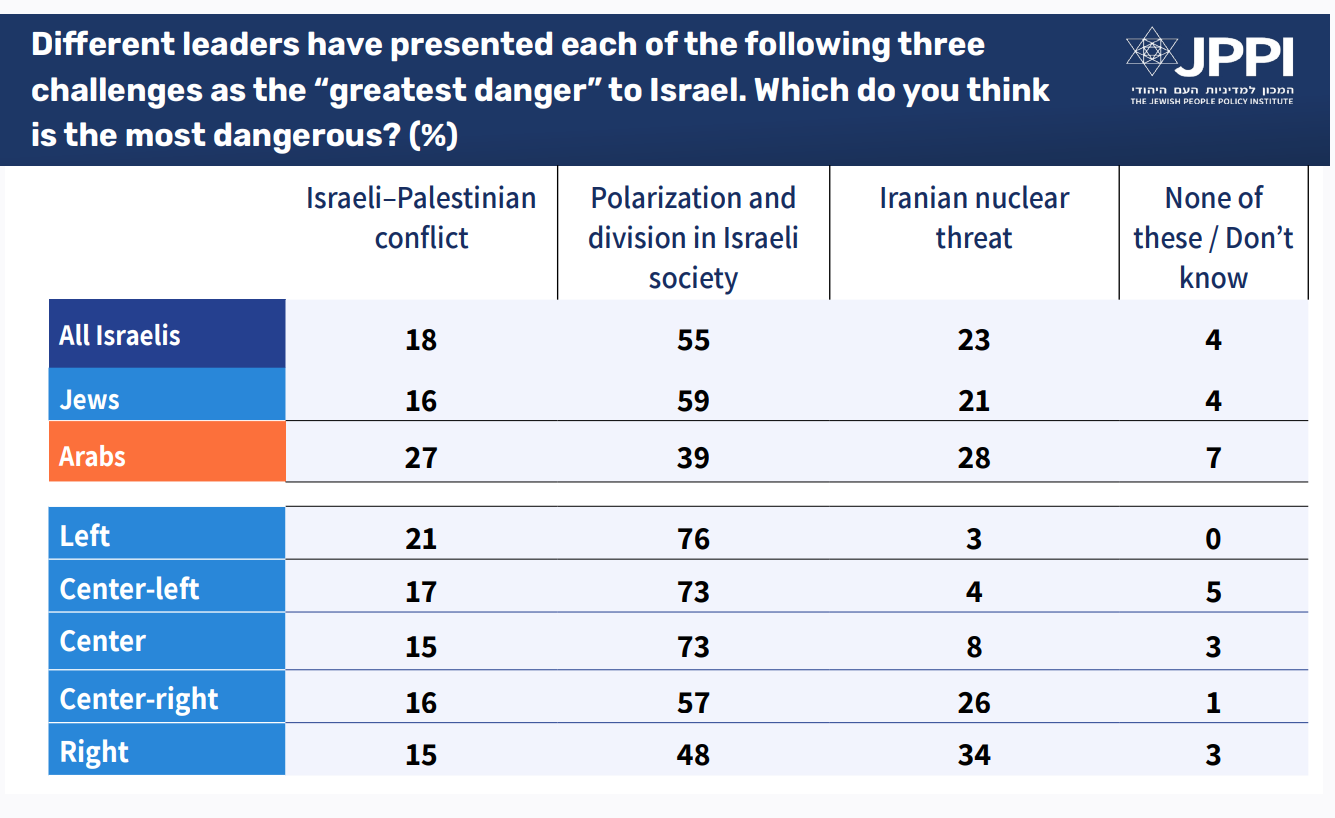

This month, we asked respondents which of three options they perceive as the “greatest danger” to Israel: the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, polarization and division within Israeli society, or the Iranian threat.

A majority of the Israeli public (55%) considers social polarization the greatest danger. A quarter (23%) single out the Iranian nuclear threat, and a fifth (18%) regard the Israeli–Palestinian conflict as Israel’s greatest danger. Among Jewish Israelis, the figures are even clearer – 59% see polarization and division within Israeli society as the primary threat. Among Arab Israelis, two in five (39%) consider polarization the main danger, a quarter (27%) cite the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, and another quarter single out (28%) the Iranian threat.

Among Israel’s left and the center-left, there is a near consensus (76%) that internal polarization is the greatest danger. The Iranian threat is perceived as the primary danger by only a small minority (3%) compared to the other options. As we move to the right, toward the larger ideological groups, the share of respondents who see the Iranian threat as the main danger to Israel rises: a quarter (26%) of those identifying as center-right and a third (34%) of those identifying as right see it that way. Nonetheless, even in the right and center-right groups, half or more (48% and 57%, respectively) believe that Israel’s greatest danger is social polarization and division.

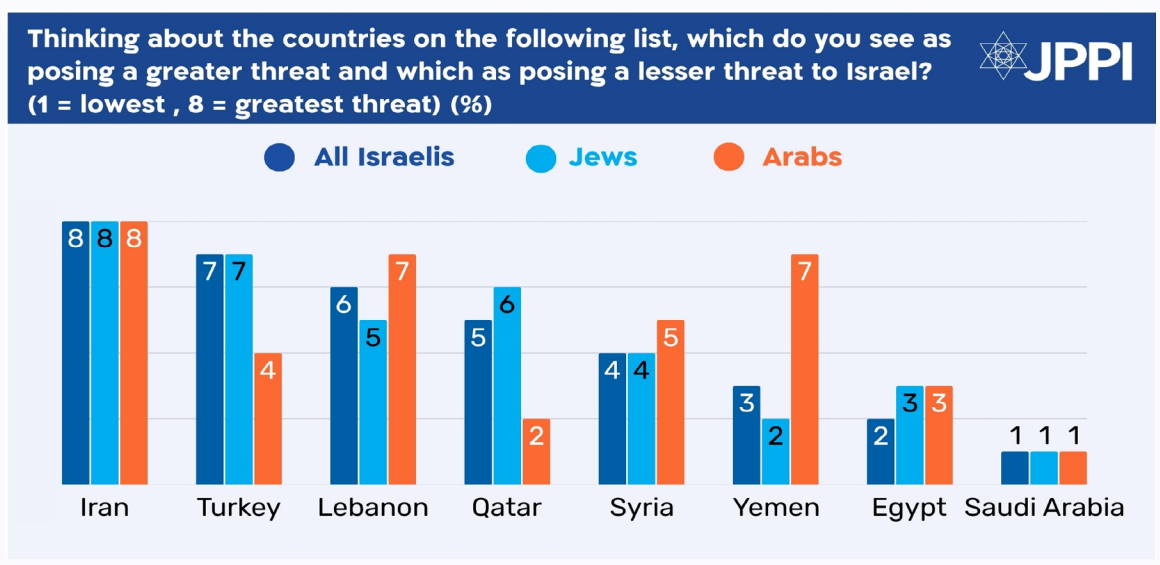

In a final question on “threats” to Israel, we asked respondents to rate eight countries according to the level of threat they pose to Israel. Among all Israelis, Iran is ranked as the greatest threat of all the countries listed, followed by Turkey and Lebanon. Qatar and Syria are perceived as the next tier of threats, while Yemen, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia are ranked as lower-level threats relative to the others on the list. Among Arab respondents, Iran is likewise ranked first; Yemen, however, is perceived as much more significant (second place), while Turkey and Qatar are ranked as lesser threats (fifth and seventh place, respectively).

Trust in Leadership and the IDF High Command

At the beginning of the month, Prime Minister Netanyahu formally requested a presidential pardon from President Herzog. His main justification for the request was “an attempt to bring about reconciliation among the sectors of the people.” The request was submitted without any admission of guilt for the offenses with which the prime minister is charged. The pardon request was also submitted against the backdrop of a public appeal by President Trump to Herzog, both orally and in writing, stating that “the time has come to pardon Bibi so that he can unite Israel.”

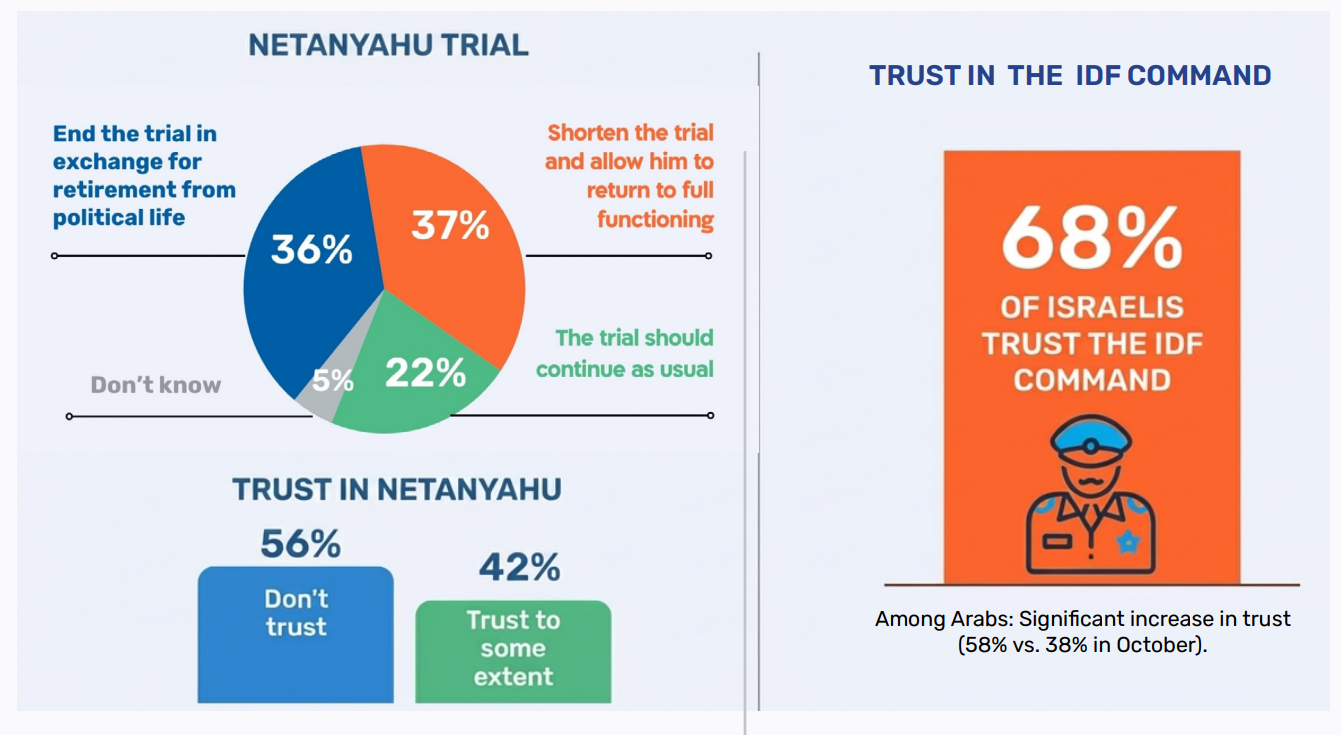

Public attitudes toward a pardon for Netanyahu were examined by repeating the identical question we asked before the pardon request. Comparing the pre- and post-request answers shows that public attitudes have hardly changed. Most Israelis believe that a way should be found to bring Netanyahu’s trial to a rapid end – 37% believe that this should be done while allowing him to return to normal functioning as prime minister, and 36% believe that this should be done in exchange for his retirement from political life. A fifth (22%) of Israelis think that an early end to the trial should not be allowed and that it should proceed as usual. Among Jewish Israelis, a higher share (44%) think the trial should end rapidly and that Netanyahu should be allowed to return to normal functioning as prime minister.

As noted, the answers remain almost identical to those given this past July, though there has been a small shift in Arab attitudes. Among Arab Israelis, 43% believe that there should be no attempt to end the trial rapidly, and only one in eight (12%) favors attenuating the trial without political sanction. This reflects an increase in opposition to intervention in the judicial process (from 35% in July to 43% now), alongside a decline in support for finding a quick solution to the trial (from 18% to 12%).

As expected, on the question of ending the trial, there are substantial gaps between ideological camps. Among those identifying as center-right, 43% support a rapid conclusion that would allow Netanyahu to return to normal functioning as prime minister, while a similar share (39%) prefer a rapid conclusion in exchange for his retirement. On the right, where most are also coalition supporters, the picture is clear: 77% want the trial to end and think Netanyahu should be permitted to return to full political functioning. Eleven percent of right-wing respondents believe the trial should continue, and another 8% think it should be attenuated in exchange for Netanyahu’s retirement from political life. In the center, a majority of 55% favor shortening the trial in exchange for Netanyahu’s retirement from political life, 24% think the trial should continue, and another 17% support shortening it without political sanctions. In the center-left, support for exchanging an end to the trial for Netanyahu’s retirement is especially high at 80%. Half of those identifying as left (52%) support a rapid arrangement that would include retirement from political life, while 48% prefer the trial to continue as normal. No respondents in the left-wing cohort support a rapid end to the trial that would allow Netanyahu to return to normal functioning as prime minister.

A majority of Israelis (56%) report that they do not trust (don’t trust at all + don’t trust somewhat) Prime Minister Netanyahu, while 42% do trust him (very much + somewhat). Among Arab Israelis, the lack of trust is even greater: three-quarters (74%) do not trust Netanyahu, and only a fifth (22%) trust him to any degree. However, compared with previous months, this month saw an increase in the share of Israelis who “trust the prime minister very much.” In fact, this month recorded the highest share of respondents reporting this level of trust since January 2024.

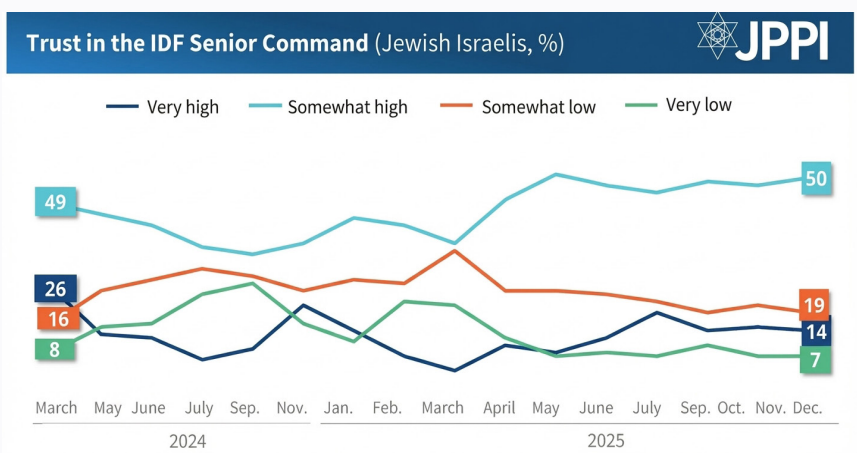

Trust levels in the senior IDF command are high, certainly in comparison with trust in the prime minister. Sixty-eight percent of the public express trust in the army’s commanders (17% “trust very much” and 51% “trust somewhat”), with the share among Jewish Israelis even higher at 70%. Among Arab Israelis, there is also a majority (58%) who trust the IDF high command. Relative to October, there has been a significant increase in the share of Arabs who say they trust the IDF (58% versus 38%), and a decline in the share whose trust is low (38% versus 53% in October).

US–Israel Relations

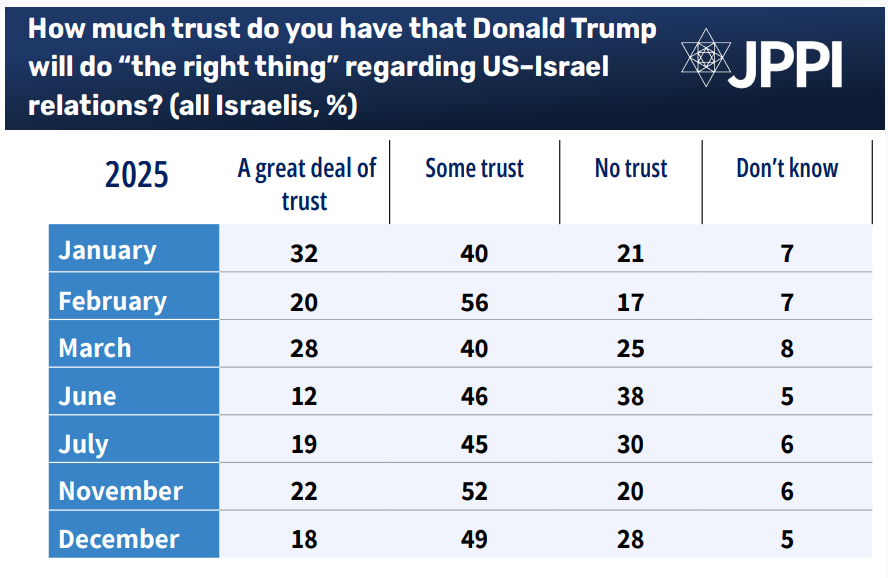

Although there are reports about disagreements between Israel and the United States regarding the next steps in the Gaza arena, most Israelis (67%) continue to express trust that the US president will “do the right thing” regarding US–Israel relations, but that trust is generally qualified. They tend to choose “some trust” rather than “a great deal of trust.” A little more than a quarter (28%) say that they place no trust in the president.

Among Jewish Israelis, trust levels are slightly higher: 70% express some degree of trust (18% a great deal and 52% some), and a quarter (27%) lack trust. Among Arab Israelis, too, a majority express some trust in Trump (55%), but this majority is smaller than among Jews. Compared with last month, there has been a slight decline in Israelis’ trust in Trump. It is possible that the higher level of trust last month stemmed from the immediate impact of the hostage-release deal signed around the time of the survey, which boosted the sense of US support. Now, trust has reverted to levels similar to those recorded before the agreement’s signing.

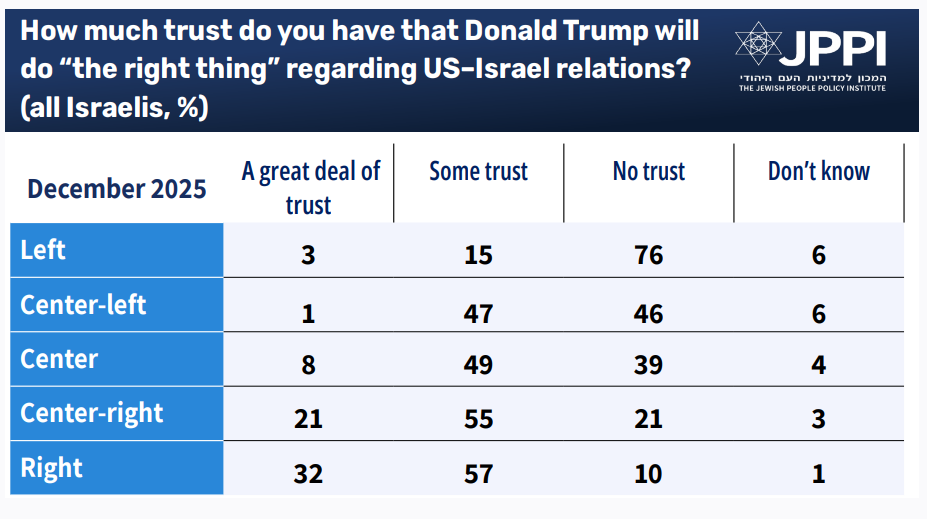

The further one moves along the ideological spectrum from right to left, the lower the share of respondents who trust Trump to do the right thing regarding US–Israel relations. Among those identifying with the Israeli left, there is a consensus (76%) that Trump cannot be trusted to act appropriately in this context. Among those identifying with the center-left, almost half (46%) report that they do not trust the president. A majority of those in the center express some level of trust (8% a great deal and 49% some), though 39% do not trust him. In the center-right, 76% express some degree of trust, and in the right, 89% say they trust him (57% some trust and 32% a great deal).

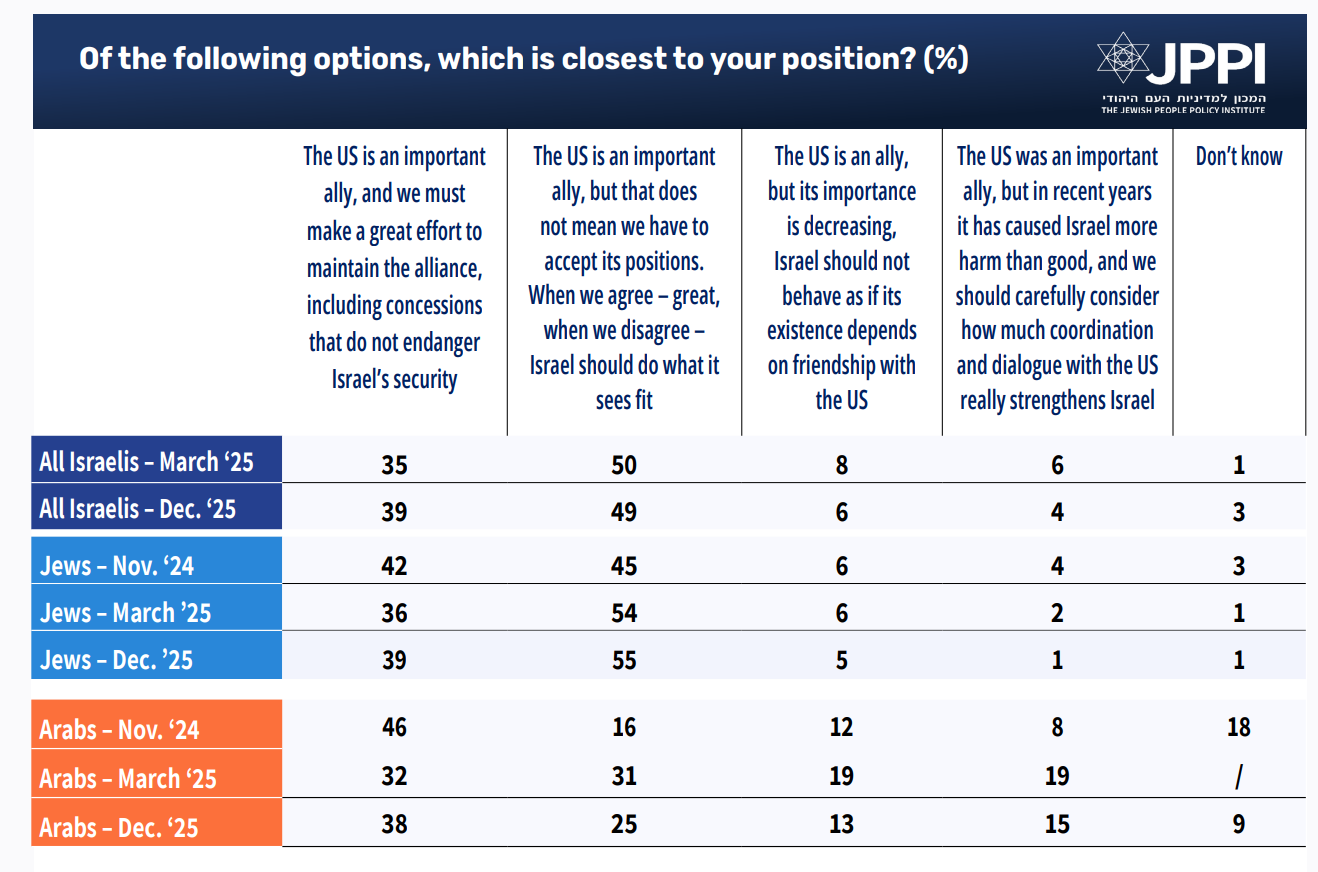

This survey also found a slight increase, relative to a few months ago, in the share of Israelis who think that Israel must make a “major effort, including compromises” to preserve its alliance with the United States. In March 2025, 35% of Israelis held this view; over the past nine months, the figure grew to 39%. There has been no change in the share who believe that Israel does not always need to adopt US positions, and that in cases of disagreement, Israel should do “what it sees as right.” Half of Israelis take this view. Six percent of Israelis believe that the United States is still an ally but that its importance is diminishing, and an even smaller share believes that the US has done Israel more harm than good in recent years. Most coalition voters (in the 2022 elections) believe that the US is an important ally, but that in cases of disagreement, Israel should do what it believes is right.

Rising Antisemitism

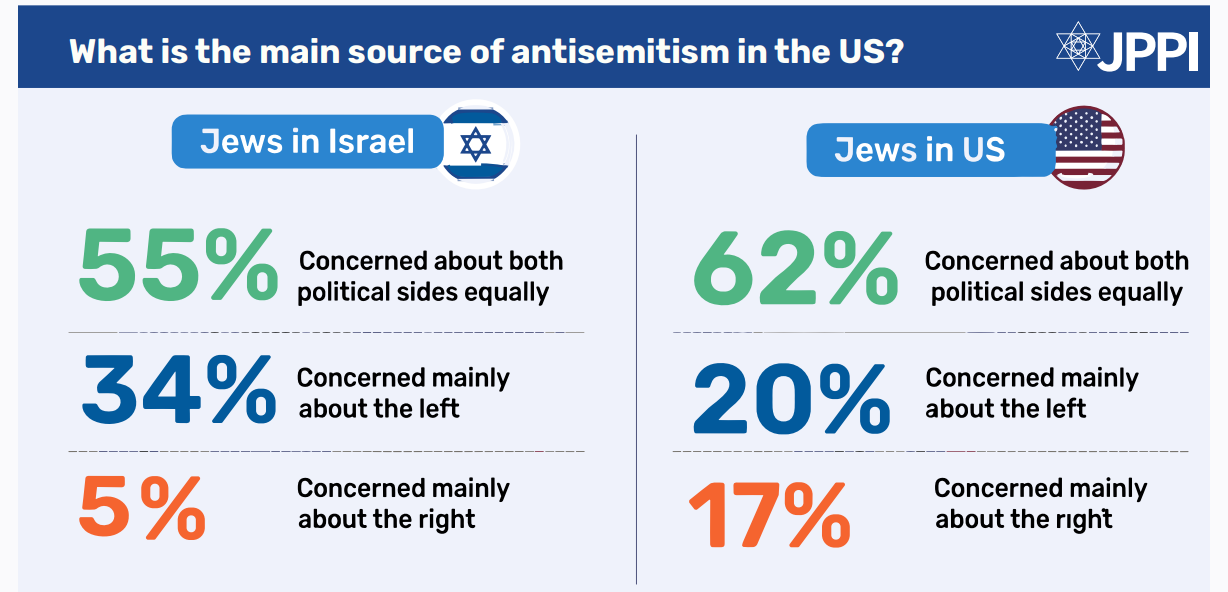

In the past two years, there has been an increase in antisemitism worldwide. This trend has been reflected, among other things, in a rise in violent incidents, vandalism against Jewish institutions, and the spread of antisemitic rhetoric on social media. The issue of antisemitism has recently returned to the headlines following the election of Zohran Mamdani as mayor of New York City and antisemitic statements by prominent figures on the American conservative right.

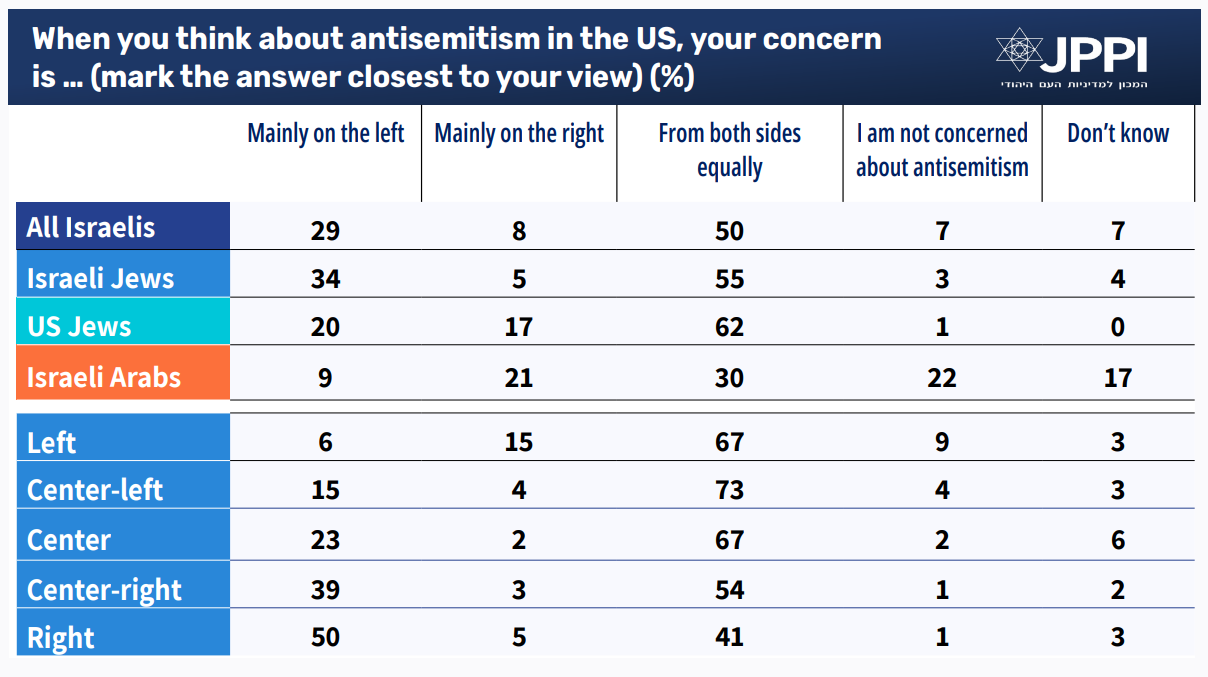

This month, we asked Israelis about the source of antisemitism in the US, and more specifically, which “side” of the political map is more concerning. Half (50%) of Israelis are concerned about both political sides to a similar extent, while 29% see the left as the main source of concern, and only 8% see the right as such. A majority of Jewish Israelis (55%) are concerned about both sides, and a third (34%) see the left as the main threat. These findings among Israelis differ substantially from those among the American Jews who responded last month to the JPPI – Voice of the Jewish People Index. Among the US Jews surveyed, 62% see antisemitism as emanating from both political camps. Moreover, unlike Israeli Jews, American Jews show similar shares who are concerned about the right (17%) and the left (20%).

Among the Israeli left and center, a majority of Jews see both sides as a similar source of concern – 67% of the left, 73% of the center-left, and 67% of the center. By contrast, 50% of right-wing Jewish Israelis and 39% on the center-right identify the American left as the main locus of antisemitism.

Israel’s International Standing

Since the outbreak of the war in Gaza, Israel’s international standing has undergone a seismic shift. In the early stages of the fighting, Israel enjoyed broad international support, mainly from the US and Western countries, which emphasized its right to self-defense. As the war dragged on, the rising number of casualties in Gaza and growing fears of a humanitarian crisis led to criticism, demonstrations, and even boycotts of Israel. Relations with some European allies became more complex, and diplomatic confrontations intensified. This month, the question of Israel’s participation in the 2026 Eurovision Song Contest was the subject of controversy. After a majority vote in favor of Israel’s participation in the event next May, four countries decided to withdraw from the competition.

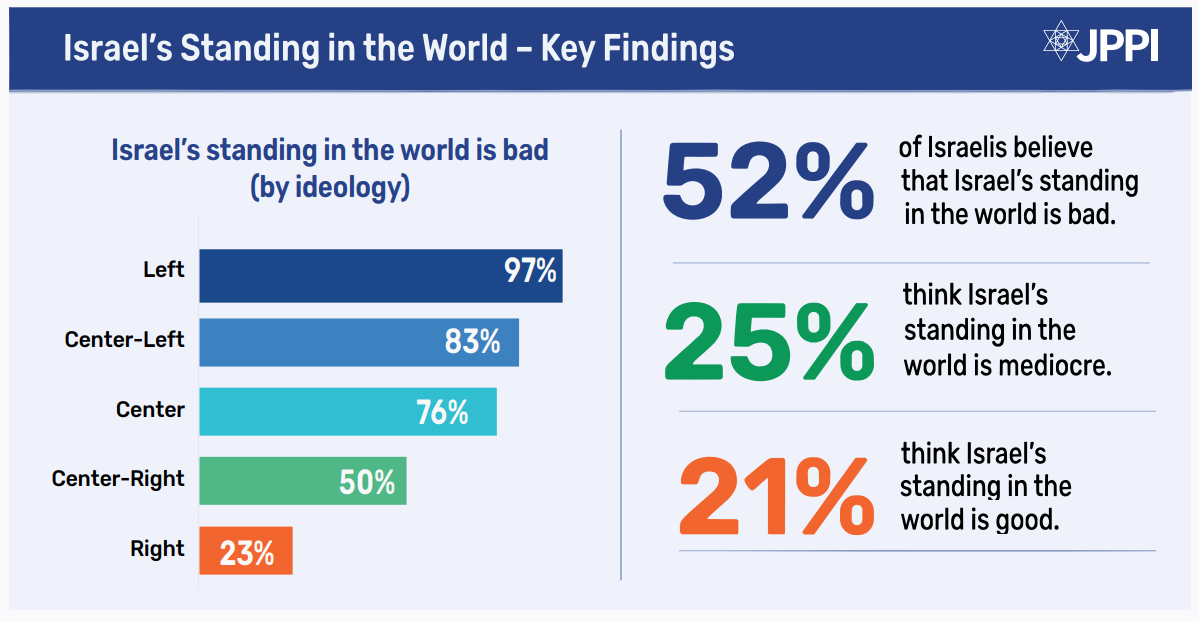

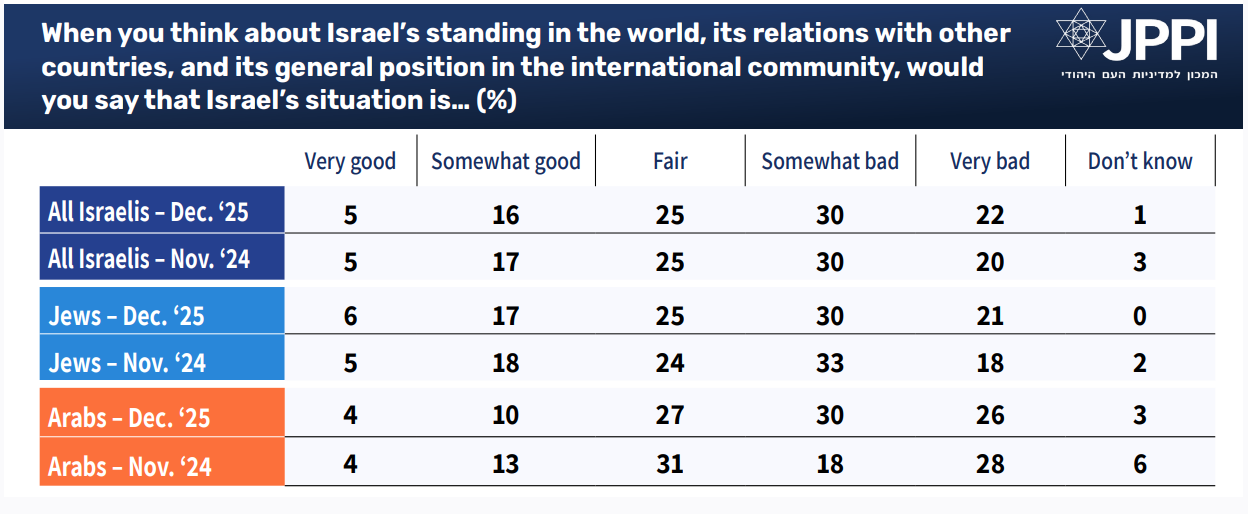

Half of Israelis (52%) believe that Israel’s standing in the world is bad (very bad + somewhat bad). Jews and Arabs agree on this. Relative to a year ago, there has been an increase in the share of Jews who say that Israel’s situation is very bad, and in the share of Arabs who think that it is “somewhat bad.” A quarter of Israelis (25%) think that Israel’s international situation is fair, and a fifth (21%) believe that its status in the international community is good (very good + somewhat good).

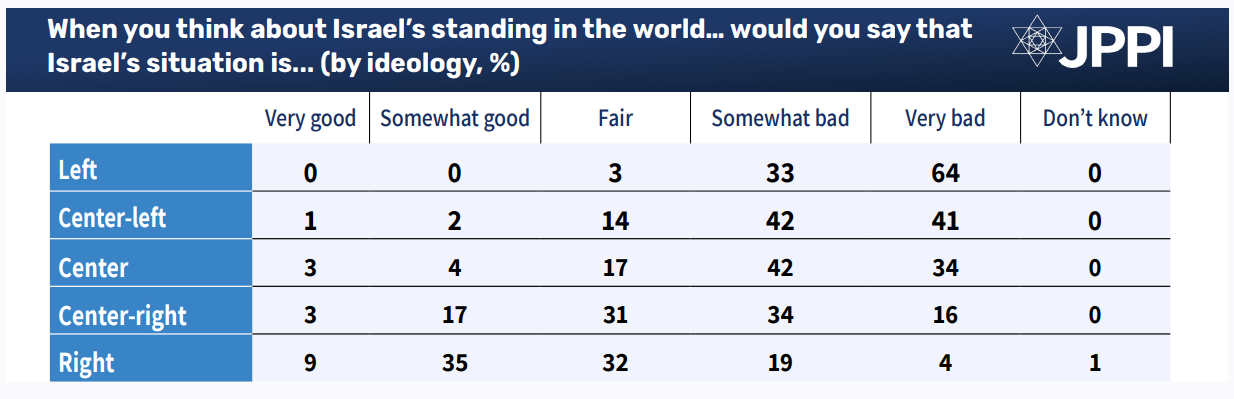

Perceptions of Israel’s international standing are strongly shaped by ideological orientation. The further one moves along the ideological spectrum from right to left, the higher the share of respondents who believe that Israel’s situation in the world is bad. With the exception of the right-wing cohort, majorities in all ideological groups believe that Israel’s international situation is bad. Ninety-seven percent of those on the left, 83% of the center-left, 76% of the center, and half (50%) of the center-right say that Israel’s international standing is bad. None of the ideological cohorts comprises a majority that believes Israel’s international situation is good.

Zionism and Racism

Last month marked 50 years since the 1975 UN resolution declaring that “Zionism is Racism” (Resolution 3379). The resolution sparked broad public debate and drew harsh criticism of the UN, even damaging the organization’s image. Sixteen years later, in 1991, the General Assembly adopted a counter-resolution (4686) rescinding the comparison. However, the claim that Zionism is a racist movement remains common in global public discourse and is used as a rhetorical tool against Israel and its policies.

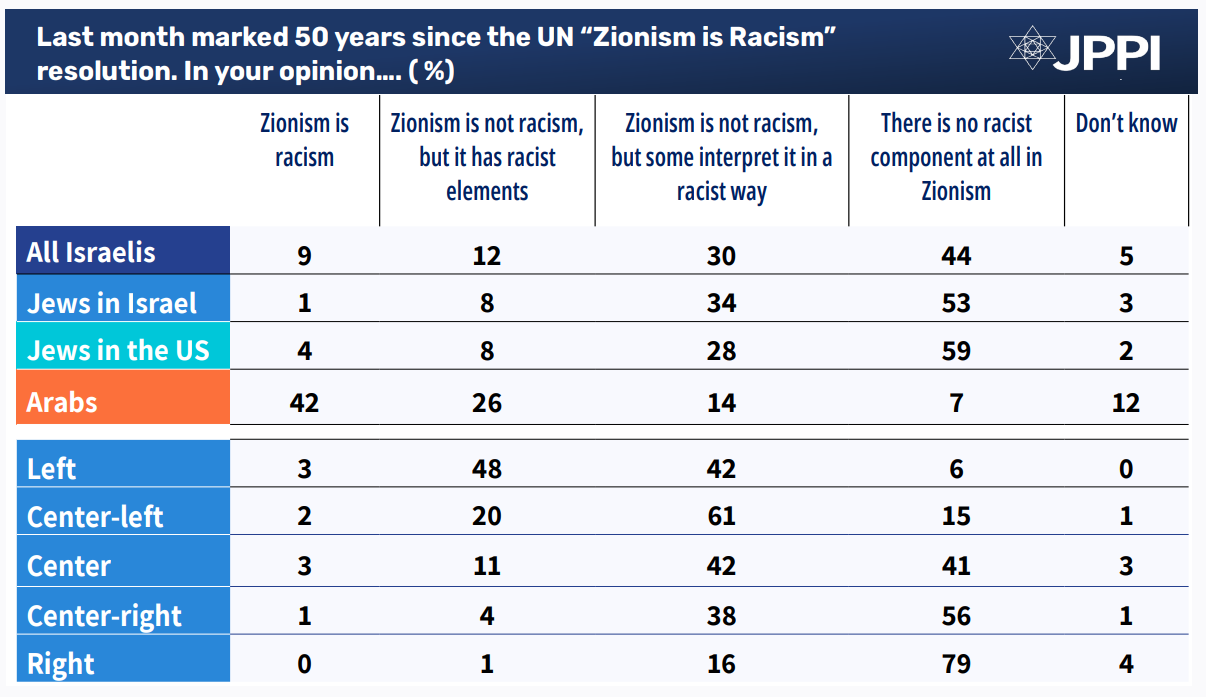

Among all Israelis, 44% believe that Zionism contains no racist components whatsoever, and a third (30%) think that Zionism itself is not racist “but there are those who interpret it that way.” One in eight (12%) thinks Zionism is not racism but does contain racist elements, and a tenth believe that Zionism is racism. Among Jews, in Israel and the US, positions are more clear-cut: more than half of Jews in both groups believe that there is no racist component in Zionism, and only a small percentage define it as racism.

Overall, “connected” American Jews (the population surveyed monthly in the JPPI – Voice of the Jewish People Index) view Zionism similarly to Jews in Israel, with minor differences: a slightly higher share of American Jews believe that Zionism contains no racist component at all, and a slightly higher share of Israeli Jews believe that some interpret it in a racist way. Among Arab Israelis, the picture is markedly different: 42% see Zionism as racist, and a quarter (26%) think Zionism contains racist elements. In all, 68% of Arab Israelis ascribe racist elements to Zionism. Only a small minority (7%) of Arab Israelis think that Zionism has no racist components at all, highlighting the deep gap between population groups in their attitude toward Zionism (among Arabs, the Druze minority stands out as somewhat less inclined to associate Zionism with racism, though even among Druze respondents, a 53% majority see racist components in Zionism).

A breakdown by ideological orientation sharpens these distinctions: the right presents a uniform view – 79% deny any connection between Zionism and racism. Among the center and center-right cohorts, the dominant group likewise believes that Zionism has no racist component (41% and 56%, respectively). In the center-left cohort, a majority believes that Zionism is not racism but that some interpret it as such. On the left, a narrow majority defines Zionism as a movement that has racist elements.

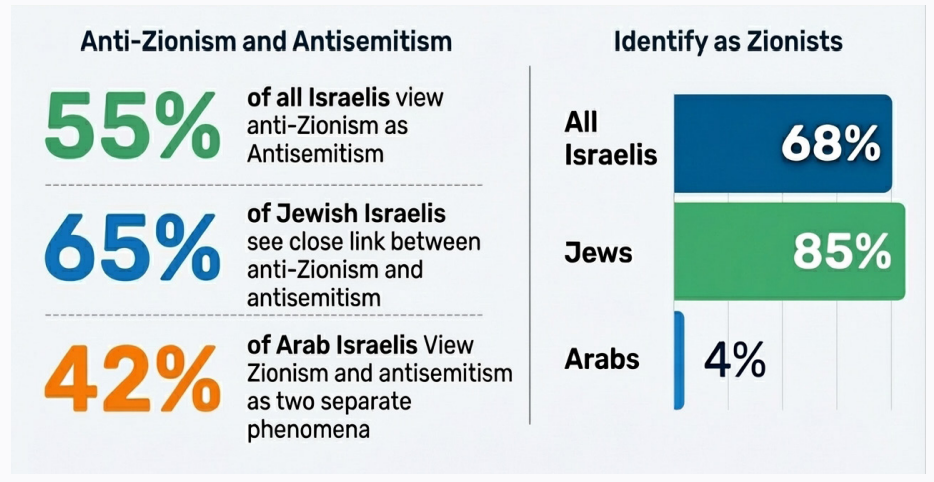

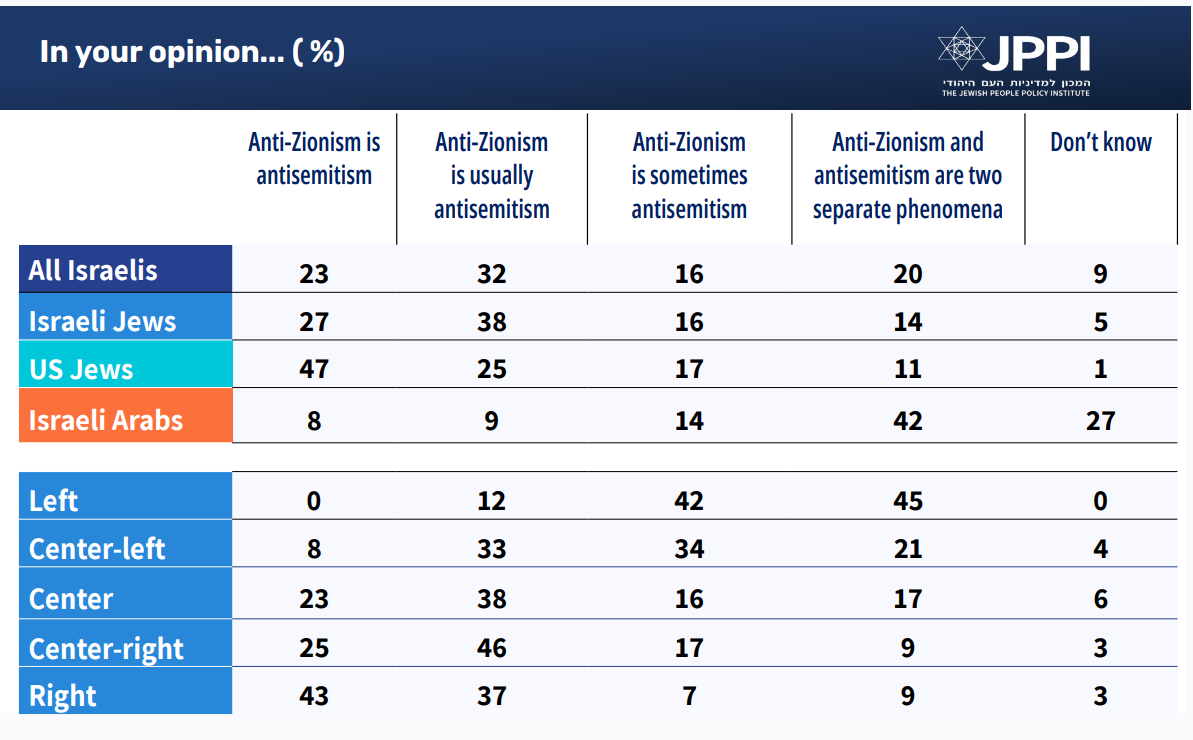

This month we also examined the relationship that respondents discern between anti-Zionism and antisemitism. A majority of Israelis (55%) see anti-Zionism as a phenomenon that is usually linked to antisemitism – a quarter (23%) say that “anti-Zionism is antisemitism,” and a third (32%) think that anti-Zionism is “usually antisemitism.” Among Jews in Israel, the connection is perceived as strong: 27% see anti-Zionism as antisemitism, and another 38% believe that it is “usually” antisemitism. Among Arabs, the picture is reversed: 42% say that anti-Zionism and antisemitism are “two different phenomena,” and only a small minority sees a link between them. Data from the Voice of the Jewish People survey among US Jews, conducted last month, indicate a gap between US Jews and Israeli Jews on this question. Almost half of US Jews surveyed (47%) see anti-Zionism as antisemitism, a far higher share than among Jews in Israel (27%).

By ideological breakdown, US Jews’ responses resemble those found on the Israeli right: 43% of those on the right in Israel believe that anti-Zionism is antisemitism, 37% think that anti-Zionism is usually antisemitic, and a tenth believe that anti-Zionism and antisemitism are two separate phenomena. On the left, almost no one sees anti-Zionism as antisemitism, and a large majority (87%) believe that it is an entirely separate phenomenon, or at most one that sometimes has a connection to antisemitism. Those in the center-left and center cohorts tend to see a relatively weak link between the two phenomena. The further one moves to the right, the stronger the perceived connection: in the center-right cohort, 71% see anti-Zionism as antisemitism or “usually” antisemitic; in the right-wing cohort, the share rises to 80%. A similar pattern – of conflating anti-Zionism with antisemitism the further one moves from strong liberal to strong conservative – was found among US Jews: while a quarter (24%) of strong liberal respondents saw it that way, three-quarters (77%) of the “very conservative” did.

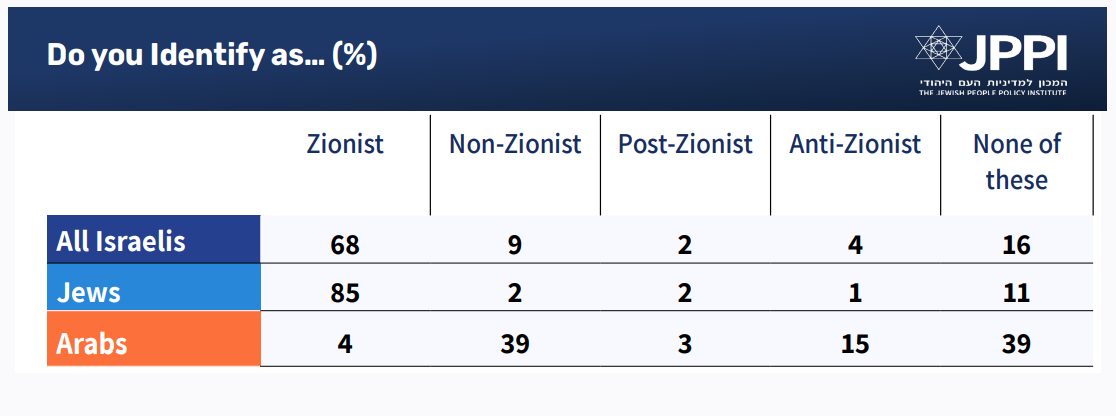

Following the questions on the nature of Zionism, we examined whether Israelis self-identify as Zionists. To this end, we presented a scale with various degrees of identification: Zionist, non-Zionist, post-Zionist, and anti-Zionist. Seven in ten Israelis (68%) define themselves as Zionists; a tenth (9%) define themselves as non-Zionists; and a sixth (16%) did not know how to answer. Naturally, there are large gaps in answers between Jewish and Arab respondents. Among Jews, the share of Zionists is about 85%, whereas it is only 4% among Arabs. Two in five (39%) Arab Israelis self-identify as “non-Zionists,” a sixth (15%) define themselves as “anti-Zionists,” and a sizable share (39%) refrained from choosing any of the categories. Among Jewish Israelis, by contrast, the shares self-identifying as non-Zionist, anti-Zionist or post-Zionist are negligible.

We also examined this question among US Jews in last month’s JPPI – Voice of the Jewish People Index. The question was identical, but the answer options differed slightly: Zionist, non-Zionist but supportive of Zionism, neither supportive nor opposed to Zionism, post-Zionist, anti-Zionist. Seventy percent of the US Jews surveyed defined themselves as Zionists, an eighth (12%) as non-Zionists who support Zionism, 7% as neither supportive nor opposed to Zionism, 5% as post-Zionists, 3% as anti-Zionists, and 4% did not know how to answer. That is, the share of Jews in Israel who define themselves as Zionists is higher than the share of “connected” US Jews who do so.

Haredi Conscription

Most Israelis (60%) oppose MK Boaz Bismuth’s proposed law to regulate Haredi (ultra-Orthodox) draft/exemption arrangements – 54% because it “will not lead to significant Haredi enlistment,” and 6% because it “places unfair pressure on the Haredim.” Relative to last month, there has been an increase in the share who oppose the law on the grounds that it will not produce meaningful Haredi recruitment. At the same time, support for it as a practical compromise remains stable, with a quarter of the public (25%) backing the Bismuth proposal. The share of those who do not know has fallen from a fifth (20%) to an eighth (13%), indicating a consolidation of attitudes in light of the public debate over the past month. Among Jews, opposition to the law is stronger than among Arabs: 59% think that the law will not lead to genuine recruitment, up from 53% last month (November). Among Arabs, the share of opponents on grounds of ineffectiveness has also risen (from 27% to 31%), but support for the compromise has also increased (from 18% to 27%), while the share of those without an opinion declined.

The further right respondents are politically, the higher their support for Bismuth’s outline. Among Likud voters in the 2022 elections, half (48%) support the law and see it as a reasonable compromise, a quarter (28%) oppose it because it will not lead to significant Haredi recruitment, and 7% support it because it will preserve the coalition. In the broad right-wing camp, whose members make up the bulk of coalition supporters, a third (32%) oppose the law because they think it will be ineffective, while 44% support it as a practical compromise, and 6% see it as a way to preserve the coalition. On the center-right, where some support the coalition, opposition to the law predominates: a majority (63%) oppose it because they don’t believe it will lead to substantial recruitment, while a fifth (20%) support it as a compromise, and an insignificant share support it for reasons of coalition stability. In the left, center-left, and center cohorts, there is near-unanimous opposition to the Bismuth proposal. One hundred percent of those on the left and 98% of those in the center-left believe that the law will not lead to significant recruitment; there is no support for the bill in these camps. Among centrists, a large majority oppose the bill on the same grounds (78%), while a relatively small proportion (11%) see it as a reasonable compromise.

Commission of Inquiry

Public opinion on establishing a State Commission of Inquiry to examine the failures that led to the October 7 attack has been divided, as shown in previous surveys. This month, we presented several options concerning who should appoint the members of such a commission. Of the options presented – all of which have been raised by various actors – the two with the greatest support are appointment jointly by Supreme Court Chief Justice Hayut’s successor, Justice Amit, and Justice Solberg (27%), and a model in which members are appointed by a balanced political division – half by the coalition and half by the opposition (28%). A fifth (21%) of Israelis support a commission assembled by Chief Justice Amit. Only a small minority supports a government-appointed commission (7%), or one appointed by the Knesset (8%). Among Jewish Israelis, support for the balanced coalition-opposition model is stronger (34%). Among Arabs, a third (32%) prefer that the commission be appointed by Chief Justice Amit, a fifth support joint appointment by Amit and Solberg, a tenth (10%) prefer appointment by the government, and another tenth (10%) by the Knesset. A relatively high share (17%) of Arab respondents did not answer this question.

A breakdown by ideological orientation reveals substantial gaps: on the left and center-left there is an almost complete preference for appointment by the Supreme Court: over 90% in both groups favor a commission appointed either by Amit alone or jointly by Amit and Solberg. Among centrists, there is also a clear preference for appointment by the Supreme Court (75%), but there is also some support for mechanisms that ensure political balance. In the center-right and right, the strongest support is for the coalition-opposition model – 37% in the center-right and 55% on the right favor this option. The right, which is the largest ideological group, is also the only group where there is some support for appointment by the government or the Knesset (12% and 15%, respectively). In other words, the right prefers that elected officials serve as the appointing authority, without Supreme Court involvement.

Violence in Arab Society

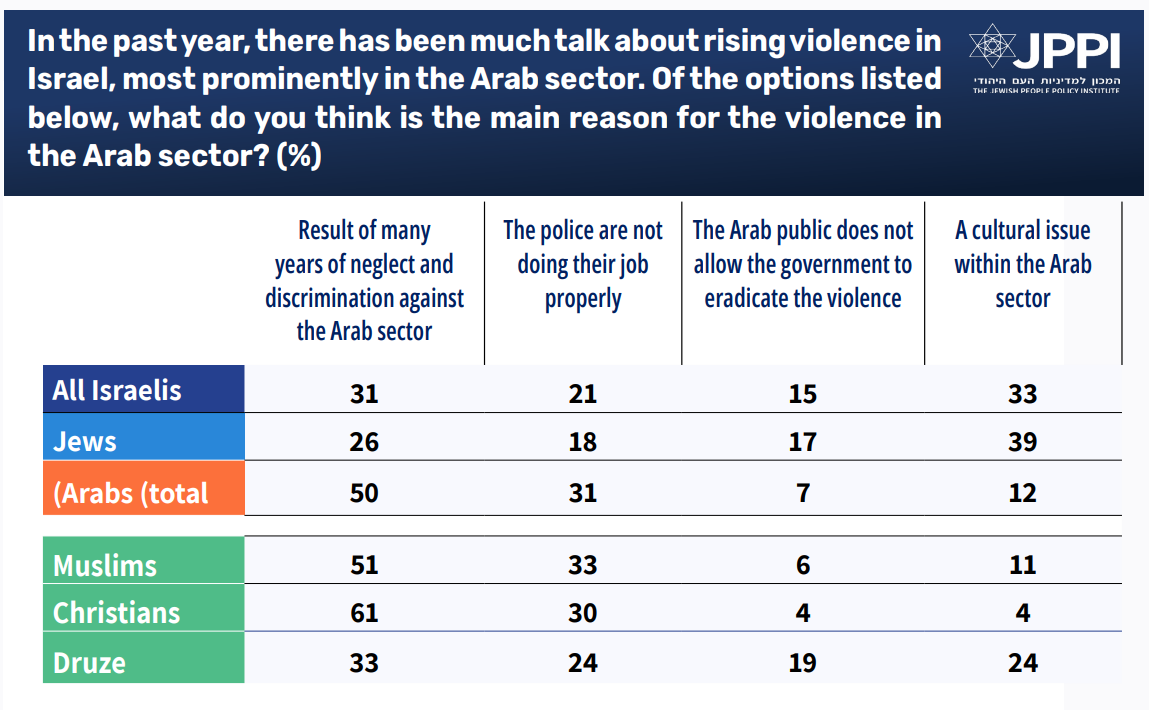

Violence in Arab society remained very high this year. A third of Israelis (33%) believe that the main reason for this phenomenon is a “cultural issue” within Arab society, while another third (31%) see it as the result of many years of “neglect and discrimination” against the Arab sector. A fifth (21%) believe that the police do not do their job properly, and a sixth (15%) think that the Arab public does not allow the Israeli government to eradicate the violence. These options were presented and examined by JPPI (in a slightly different way) three years ago.

Among Jewish Israelis, 39% attribute violence in the Arab sector to a “cultural issue,” while a quarter (26%) see it as the result of prolonged discrimination. A fifth (18%) of Jewish Israelis blame the police for not doing their job properly, and another fifth (17%) believe that the Arab public itself does not allow the government to act. Among Arab Israelis, the picture is reversed: half (50%) see the violence as a direct result of years of neglect and discrimination, and a third (31%) blame the police – that is, 81% of the Arab public see state institutions as the main source of the problem. One in eight (12%) Arab respondents point to cultural factors, and fewer than a tenth (7%) blame the Arab public itself.

In winter 2022, we asked an identical question. Respondents were asked to rank the same four options, indicating which is the primary, secondary, and tertiary cause, etc. The distribution among Jewish Israelis that year was as follows: 37% thought that violence was a “cultural issue” in Arab society; 35% that it was the result of years of neglect and discrimination; 15% that the police were not doing their job properly; and 14% that the Arab public did not allow the government to eradicate the phenomenon. Arab responses in 2022 were as follows: 40% saw violence as the result of prolonged discrimination; 37% thought the police were not doing their job properly; 14% thought it was a “cultural issue”; and a tenth (9%) thought the Arab public did not allow the government to eradicate the violence. That is, as in the past, Jews tend to assume – perhaps even somewhat more than in the past – that responsibility for violence in the Arab sector stems largely from social dynamics within Arab society, while Arabs assume that the blame lies with the Israeli authorities, which fail to pursue an adequate policy.

Separation between Sectors

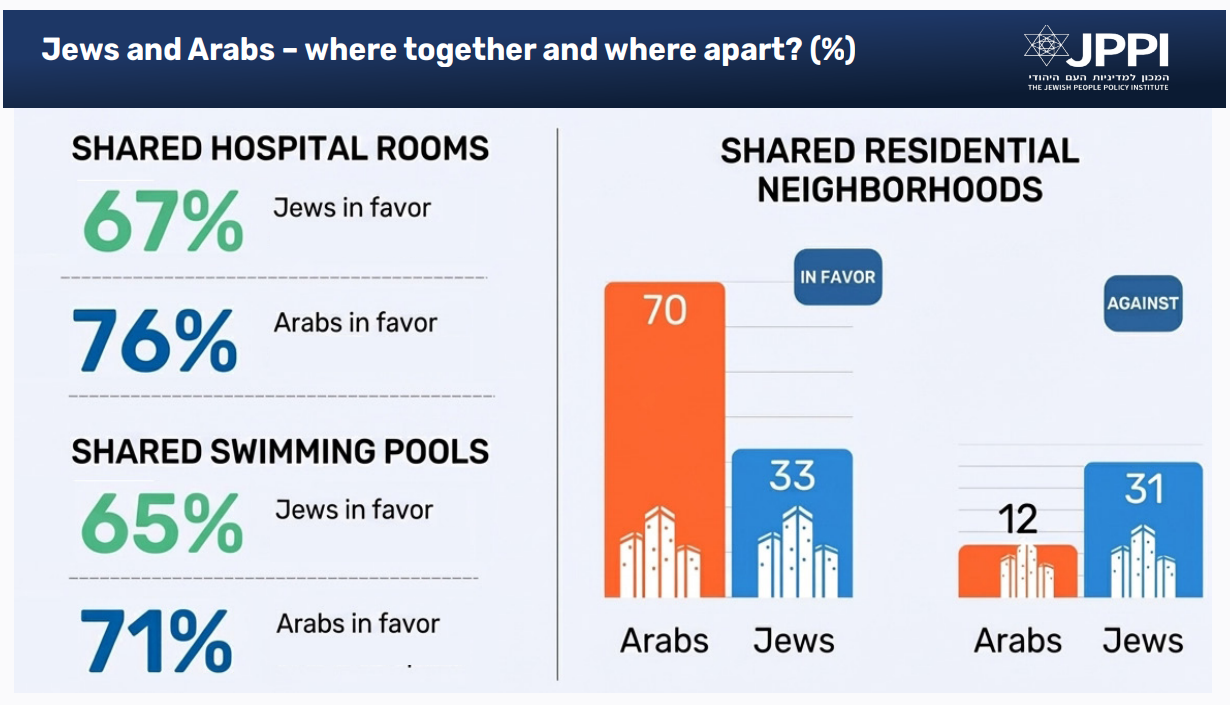

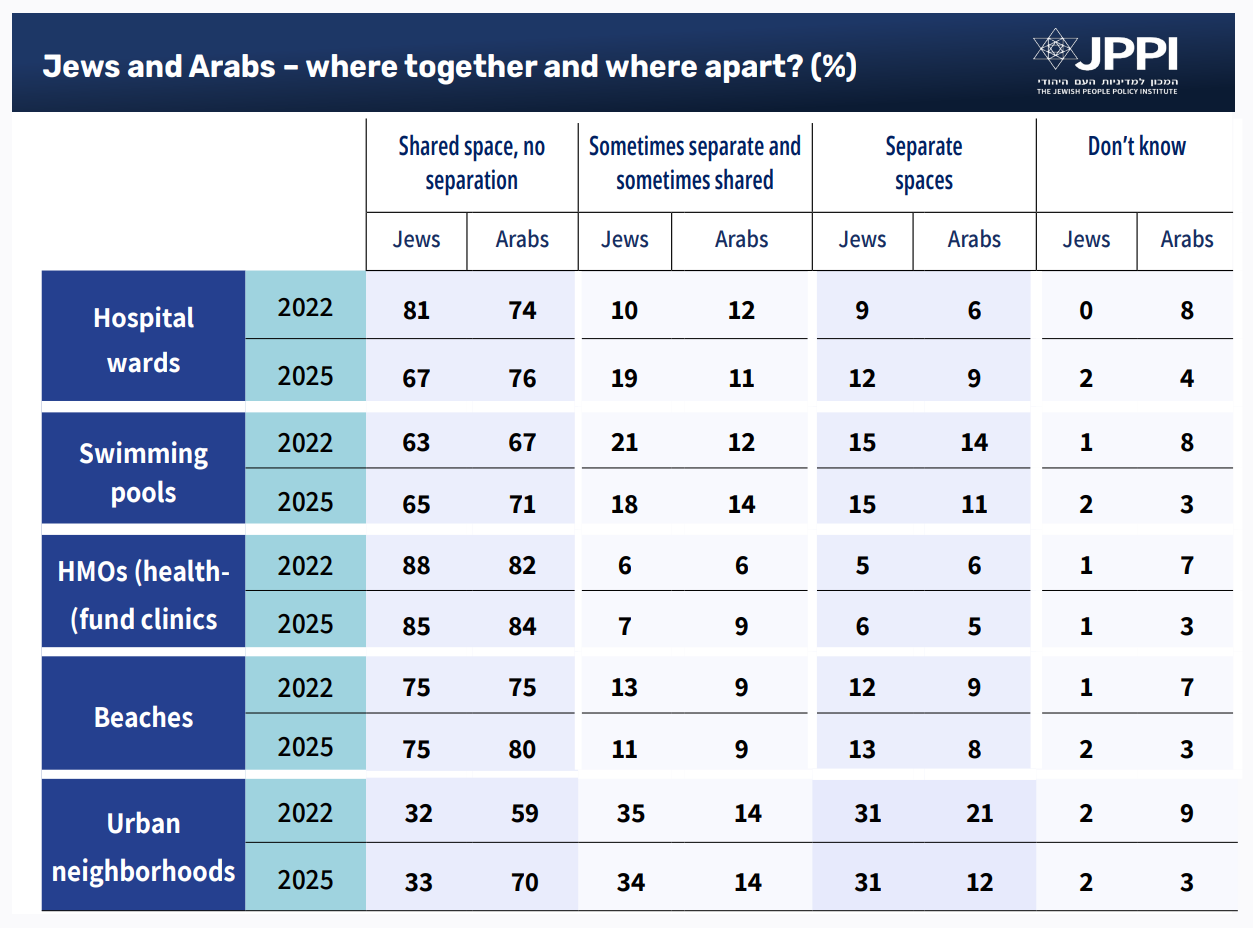

In recent years, the question of separation between sectors in public spaces has arisen repeatedly. Similar to the previous question, this issue was examined in a previous JPPI survey, and we revisited it this month to assess agreement and disagreement regarding the co-presence of Jews and Arabs in public spaces. The comparison is between a 2022 JPPI survey and the present survey. Some shifts are evident in the shares choosing various answers, but overall support for shared public spaces – apart from residential neighborhoods – remains high.

In healthcare settings, such as hospital wards and HMOs (health-fund clinics), support for shared spaces remains high, but there has been some degree of change relative to three years ago. Among Jewish Israelis, there has been a decline in support for shared hospital wards (from 81% to 67%), while among Arab Israelis, support has actually risen slightly (from 74% to 76%). With respect to HMOs, support has remained stable: 85% of Jews and 84% of Arabs support non-segregated spaces. Thus, even after these changes, healthcare settings continue to be perceived by most of the public as places where integration is desirable and acceptable.

In leisure spaces, such as swimming pools and beaches, attitudes are similar to those in 2022. About 65% of Jewish Israelis and 71% of Arab Israelis support shared swimming pools; the figures are similar for beaches (75% and 80%, respectively). The share preferring separation in these domains remains relatively low, and the number of undecided respondents has declined.

The most striking gap concerns residential neighborhoods. Among Jews, a third (33%) support mixed neighborhoods, while Arab support for mixed neighborhoods has risen from 59% to 70% over the past three years. In this same period, the share of Arabs favoring separation in residential neighborhoods has dropped from 21% to 12%. Among Jews, by contrast, there has been no change: a third (33%) support mixed neighborhoods, a third (31%) prefer separate neighborhoods, and a third (34%) prefer “sometimes separate and sometimes mixed.

Survey Data and Methodology

Data for JPPI’s December 2025 Israeli Society Index was collected between December 1 and 4, 2025. Data collection was conducted via the “theMadad” website panel (634 Jewish respondents in an online survey) and Afkar Research (200 Arab respondents, roughly half online and half by telephone). The data was analyzed and weighted by voting pattern and religiosity to represent the views of the adult population in Israel. The JPPI Israeli Society Index is compiled by Shmuel Rosner and Noah Slepkov with research, production, and writing assistance by Yael Levinovsky. Prof. David Steinberg serves as statistical consultant.