The State of Israeli Cohesion: Between Crisis and Opportunity

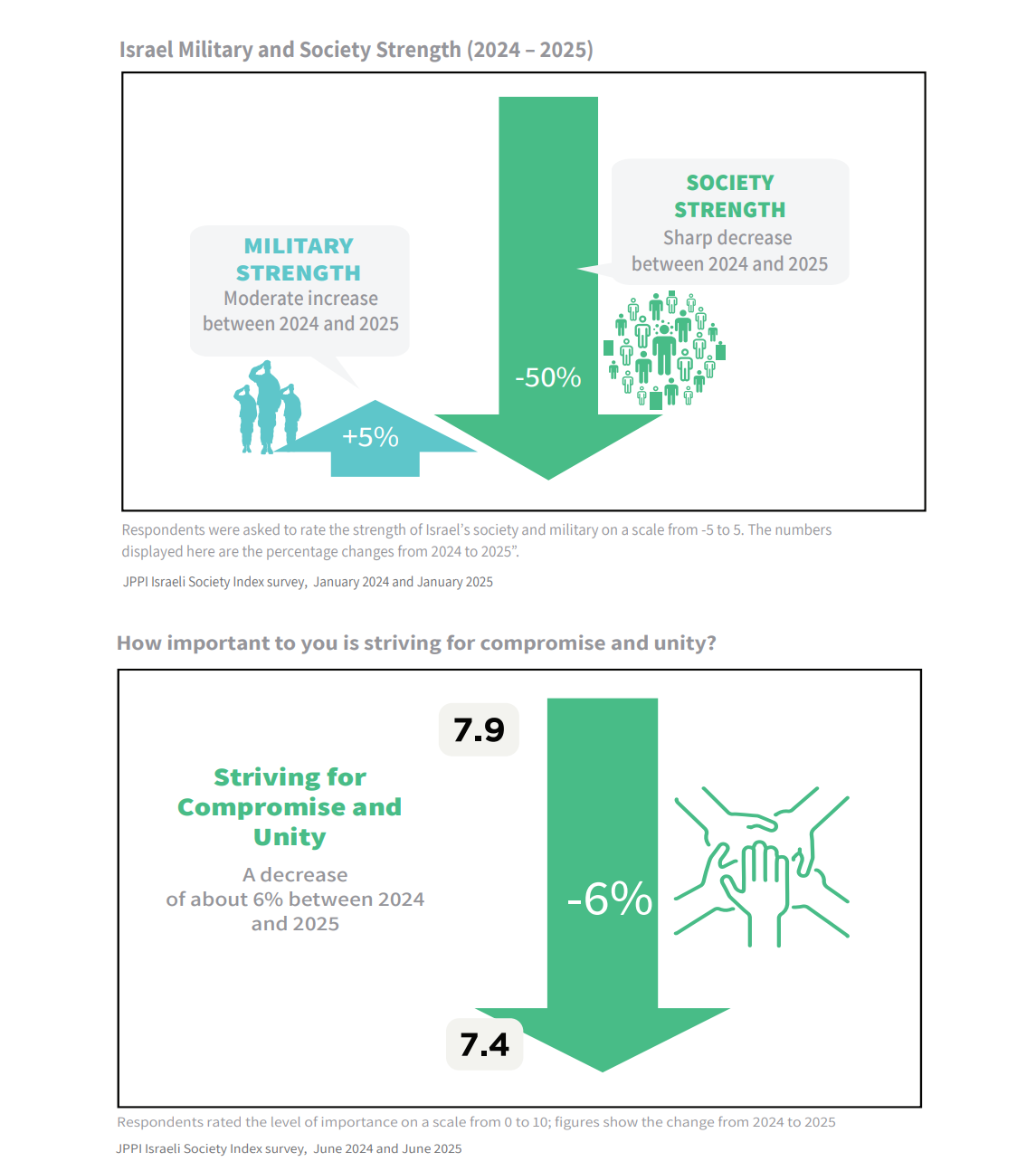

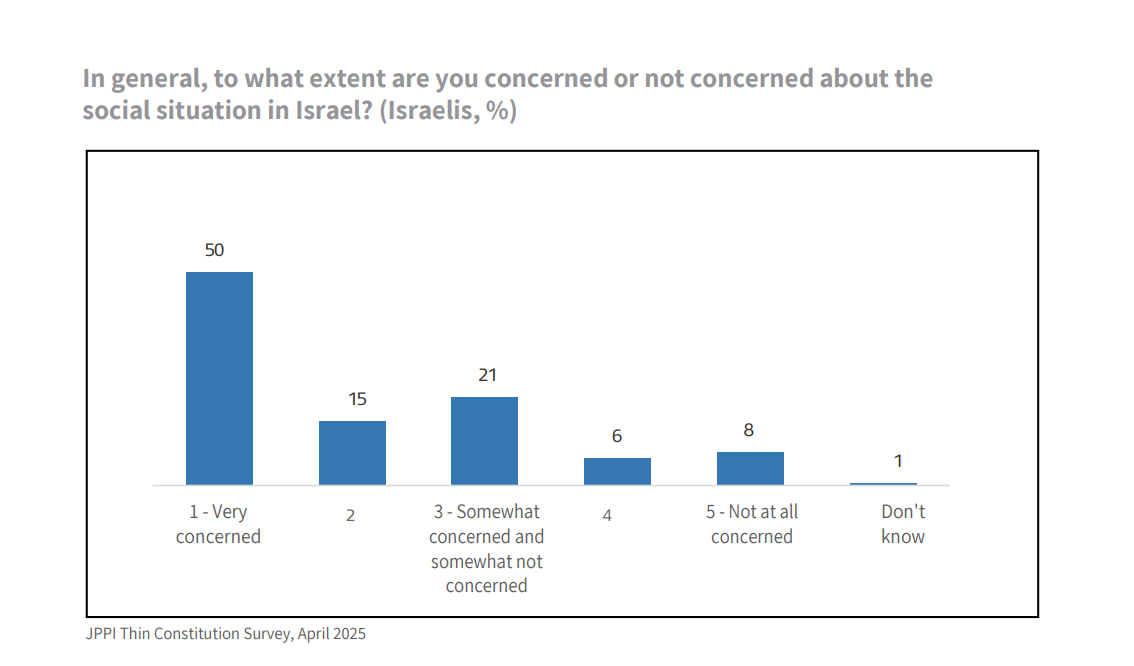

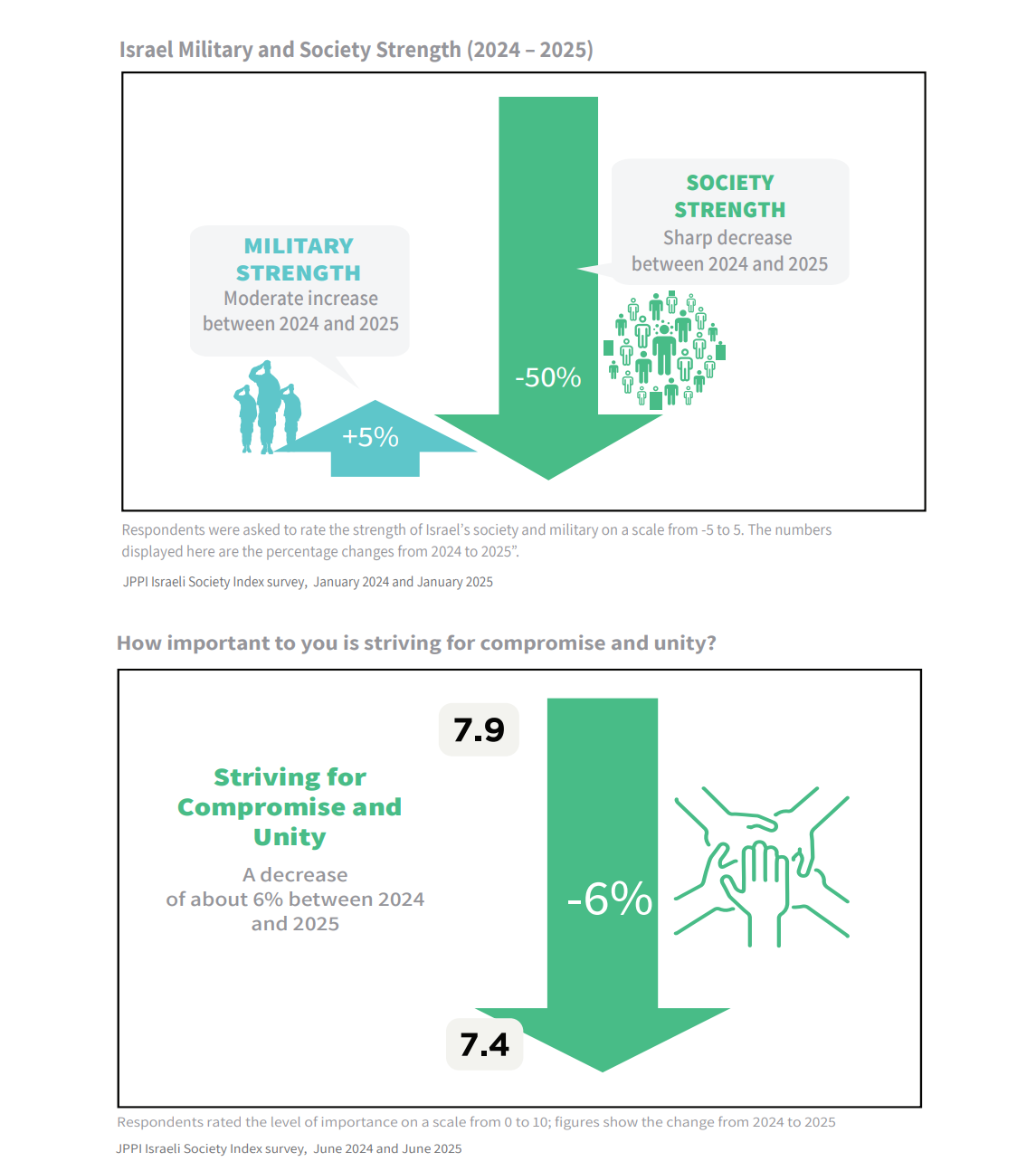

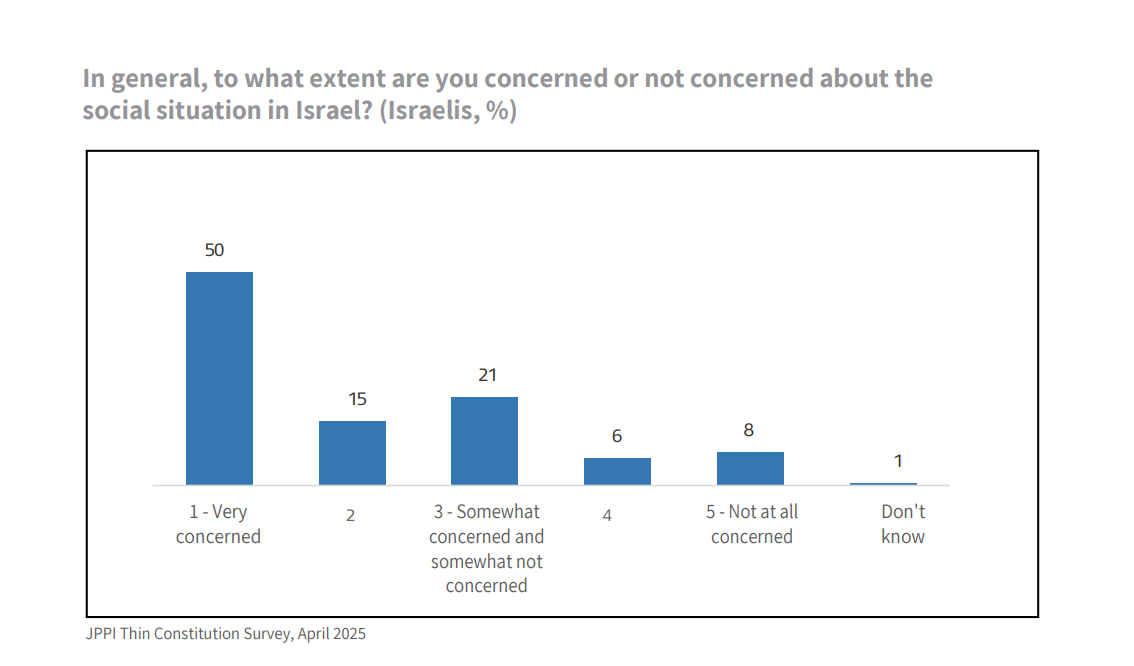

Israel is enmeshed in a deep social and political crisis that has persisted for several years. A majority of the Israeli public (79%) is understandably concerned about the prevailing social situation. In JPPI’s April 2025 Israeli Society Index survey, about a quarter (27%) of Israelis agreed with the assessment that Israel “is very close to civil war.” A third (33%) felt the assessment was an exaggeration but still believed that “the danger is real.” The overall sentiment expressed by the public is that of a desire to strengthen cohesion; at the same time, Israelis’ willingness to compromise on their positions in order to reinforce cohesion has declined this year compared to last year. This state of affairs may result from the fading shock of the October 7 onslaught, which evinced, at least temporarily, a sense of unity in the face of a common external enemy.

The roots of the social crisis can be traced back to various times depending on one’s perspective. The rise of the Netanyahu government in 2022 undoubtedly intensified the crisis. But its presence had been felt at least since the start of the period in which Israel underwent several repeated and closely spaced inconclusive election cycles (2018-2022). Myriad explanations address the deep underlying causes of this state of affairs, and there is a clear connection between the situation in Israel and similar developments in countries around the world. Polarization in Israeli society has been fueled by substantive and fundamental disagreements, including disputes over Israel’s identity; interest-driven factionalism among diverse identity groups characterized by differing degrees of traditional practice and attitudes toward Western values. These social factions compete for influence and dominance via collective and personal identification with leaders and political parties, which is partly driven by cultural gaps rooted in education and income disparities. All this is, of course, amplified by social and mass media, which exploit a polarized version of reality for the sake of ratings and profits.

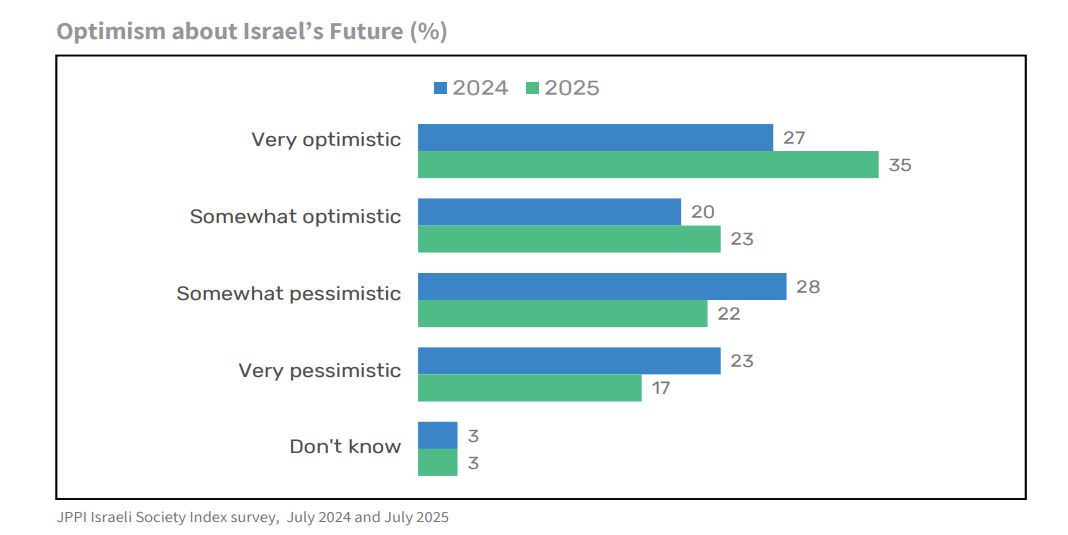

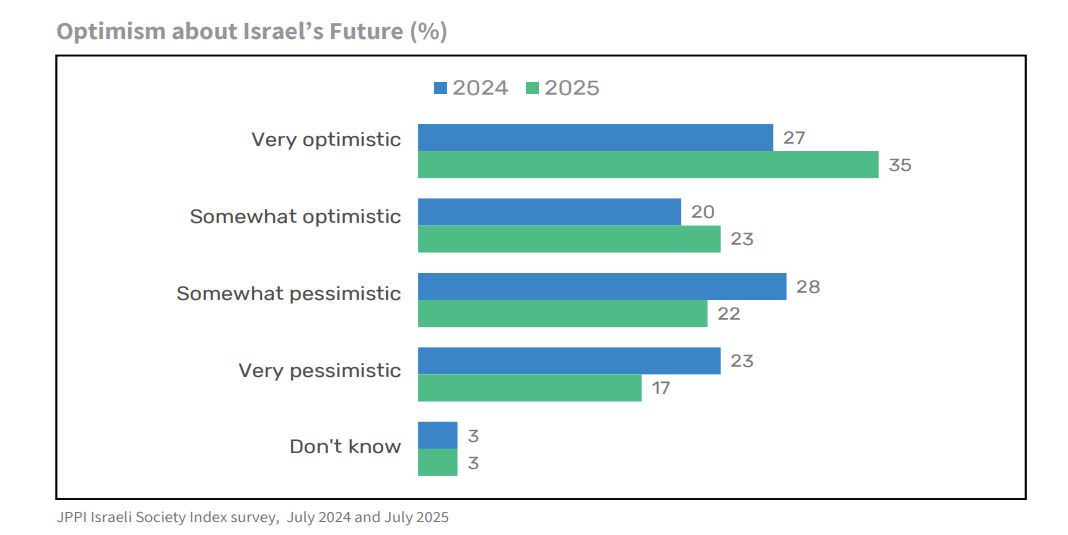

At the onset of the Israel-Hamas war in October 2023, there was reason to hope that the strength required to face the external enemy would enable a kind of social reboot. In this state of crisis, Israeli society tapped into deep reserves of commitment and solidarity, and a spirit of volunteerism and sacrifice. It is no coincidence that Israel ranks near the top of many international indices of personal and communal satisfaction. JPPI’s July 2025 Israeli Society Index found that Jewish Israelis (though not Israel’s Arab minority) have high levels of interpersonal trust, and especially trust in other Israelis of a similar ilk. Here, too, Israel is near the top of international rankings of interpersonal trust.

There is a broad Israeli consensus on many issues, however deep the ideological divide may appear to be – and at least some Israelis seem aware of this fact: In JPPI’s July Israeli Society Index, 57% of respondents agreed (“completely” or “somewhat”) with the statement: “On most important issues, most Israelis agree with each other.” Some 61% of Jews agreed with this statement, as did a majority across ideological cohorts except the relatively small “left-wing” respondent group. Indeed, it is not hard to find areas where Israeli consensus exists. For example, a large majority of Jewish Israelis support the idea that Israel should be a Jewish state. A very large majority of Israelis, Jews and Arabs, attach importance to Israel being a democratic state. In both cases, there is also a majority of Israelis who interpret the terms “Jewish” and “democratic” in ways that reflect complexity (for instance, agreeing that a “democratic” state means a state characterized by both majority rule and the safeguarding of human rights).

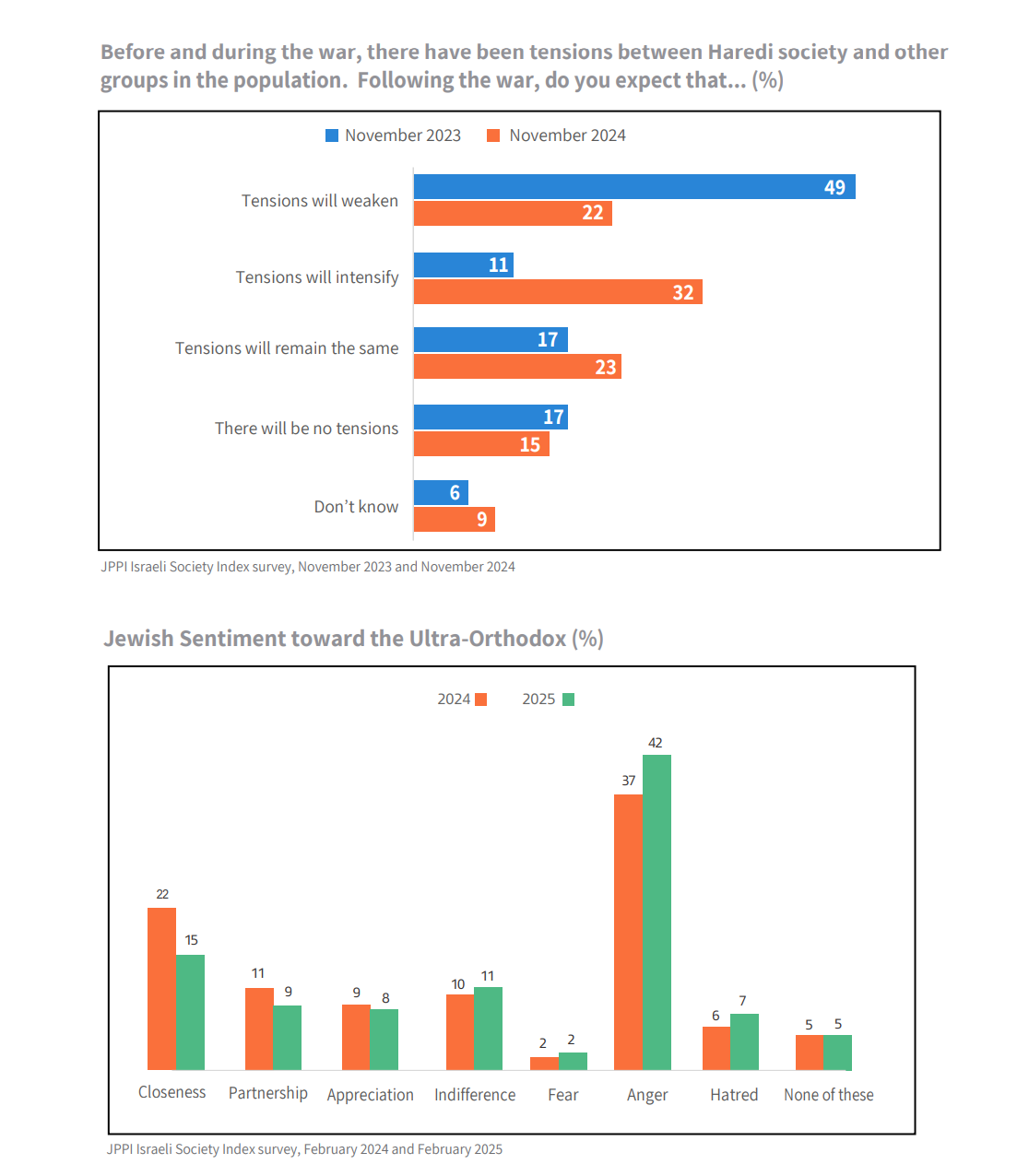

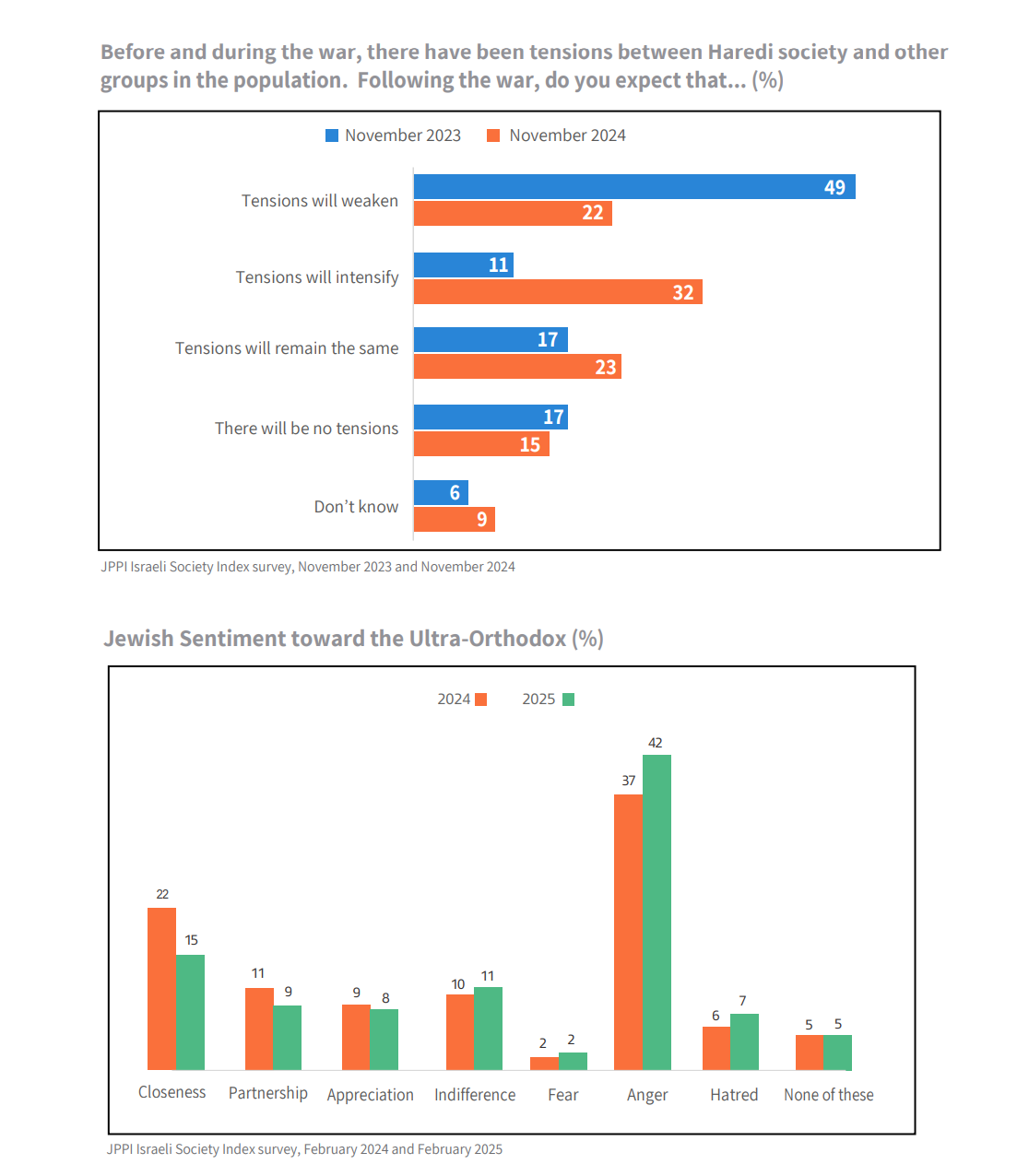

Nevertheless, strong communal currents are not the same as overall social cohesion. Perhaps this is because Israelis tend to forget how widespread their agreement is and focus instead on issues where disputation prevails. As a result, Israeli society mobilized for the war as though there were no social crisis and allowed it to persist as though there were no war. In certain areas, the crisis may have even worsened due to the war, as the ideological confrontation between Israeli “camps” over the right path for the country to take became more acute in light of the great risks and sacrifices required for victory. Disagreements over certain issues not directly related to the war (such as the authority of the Supreme Court) have not abated, and new sharp disputes related to the war have emerged (who bears responsibility, under what conditions should the war end, what price should be paid for the hostages’ return, and so on).

As noted, the social crisis stems from many sources and has implications across various spheres. This chapter examines three main aspects of the crisis and how they should be addressed. The first is the political dimension, and the implications of the crisis for Israel’s next elections and the government that will be formed after. The second is Israel’s handling of the Haredi (ultra-Orthodox) challenge – especially the issue of military service for young Haredi men. Third and most important is the difficulty of stabilizing Israeli system of governance in a way that prevents recurring social crises. Regarding this last issue, JPPI is working on drafting an agreed-upon “thin constitution,” whose urgency has become even more apparent this year than in previous years.

The Political System: Fateful Elections

Israeli elections are currently scheduled for October 2026, which means they will come after the publication of JPPI’s next Annual Assessment. However, within the political establishment, the expectation is that Knesset elections will be held during the coming year, bringing an end to one of the most turbulent and dramatic terms of any Israeli government.

The sitting government enjoys a fairly stable Knesset majority, having expanded to 68 seats. Nevertheless, it does not enjoy significant public trust. Indicators that have been assessing the government since the last elections show a large gap between the formal support its electoral victory demonstrated and the level of public support it has now. For most of its term, confidence in the government has hovered just above 30%. This figure emerged almost immediately after the government was established, coincident with the public outcry that erupted over its proposed “judicial reform” – and did not significantly change in the wake of the October 7 attack, or during the long months of war that followed. An uptick of public confidence in the government occurred only toward the summer of 2025, in the wake of the Iran campaign (Rising Lion). Yet even this shift left only a minority of Israelis reporting confidence in the government and the prime minister.

A situation in which a government operates with a stable parliamentary majority but does not enjoy public trust is far from ideal. It results in many governmental actions being perceived as contrary to the public’s wishes. The government becomes frustrated by the lack of public support even when achieving successes, while the public becomes increasingly frustrated that the parliamentary majority seems desensitized and indifferent to public sentiment. In many cases, the majority of the public believes that government actions are driven by the desire to preserve its parliamentary majority, rather than a commitment to improving the country’s situation.

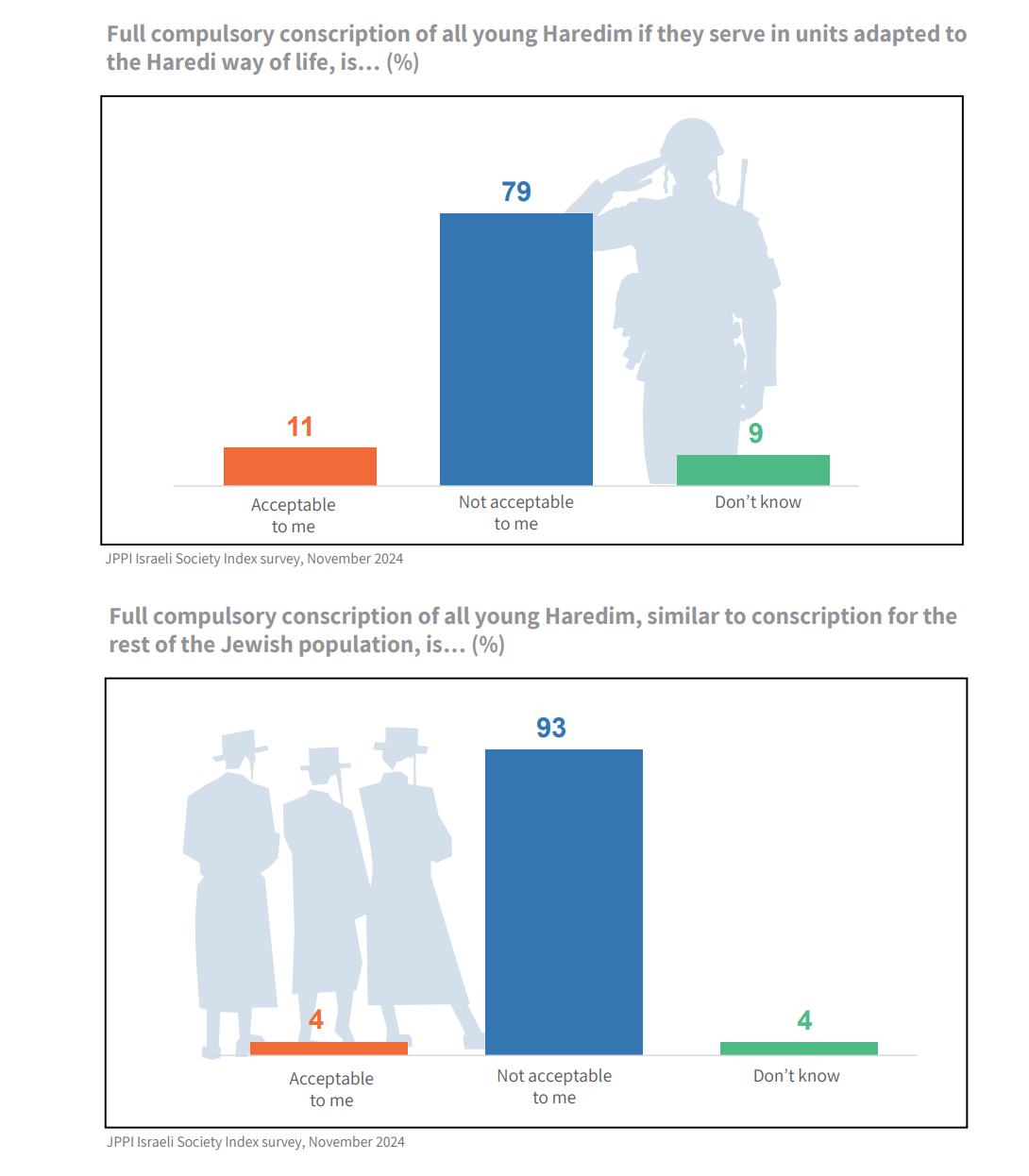

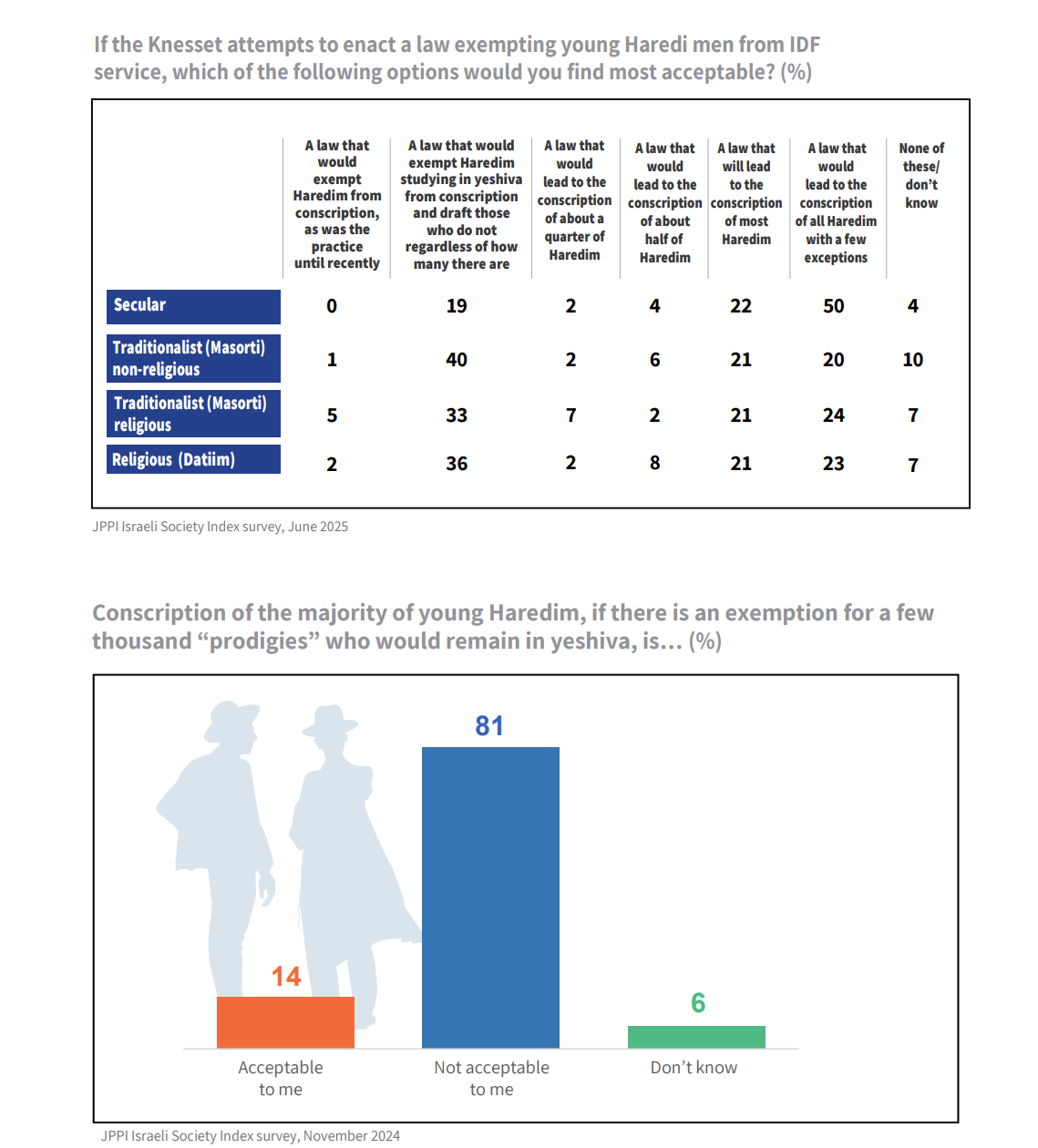

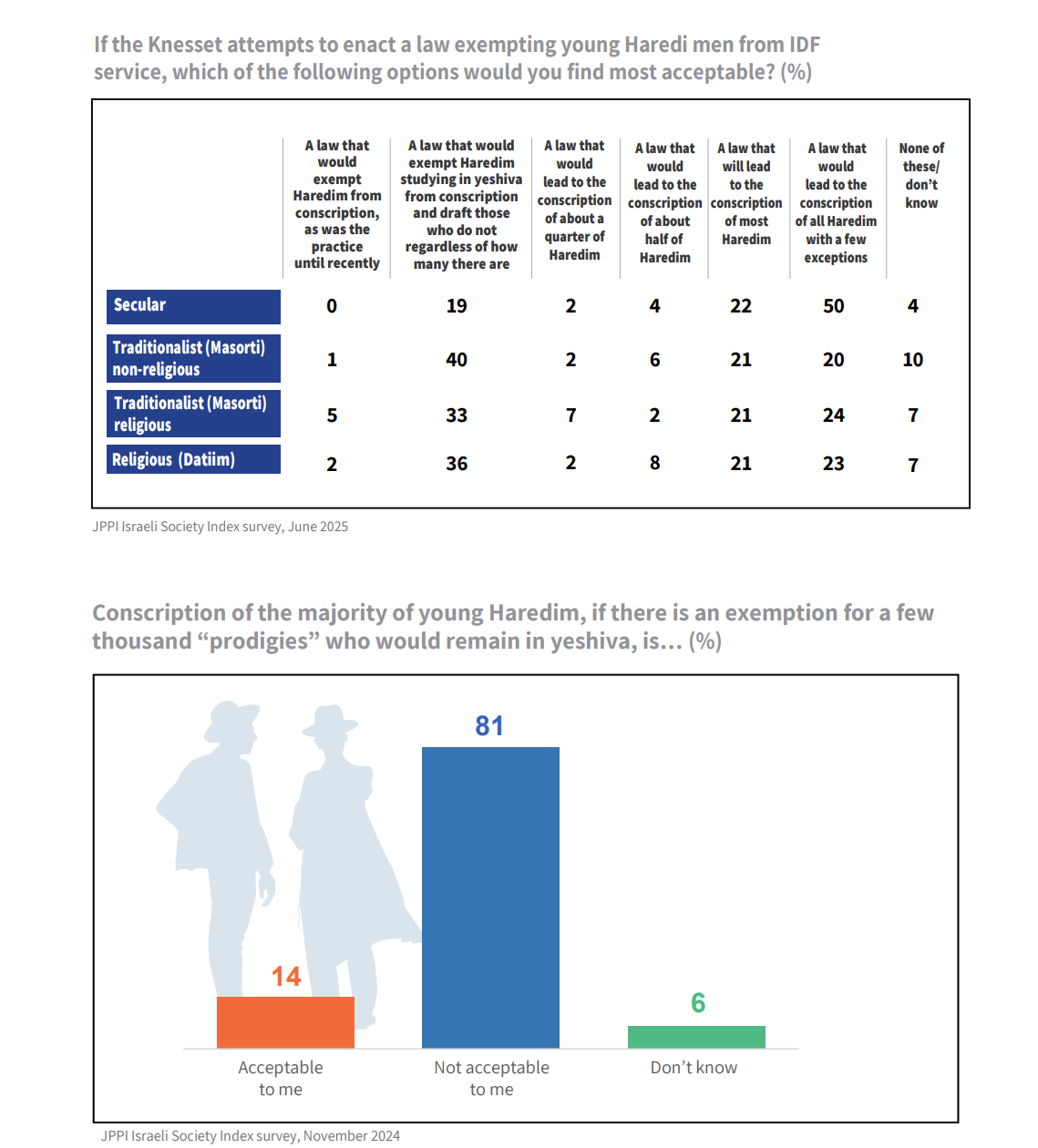

This fact was especially evident during the period of large-scale protests against the judicial reform, when polls repeatedly showed that the government lacked the support of most Israelis (including a share of the public that, in principle, did support some of the government’s proposals, but opposed the way the government conducted itself and was concerned about the cost to Israeli society). This was replicated during the public debate over priorities in the prosecution of the Gaza war (put simply: whether it was more important to bring the hostages home or to topple Hamas). Here, too, the government took steps that most Israelis opposed. The gap between the government’s positions and the views of most of the public is also, of course, highly conspicuous in the debate over the conscription of young Haredi men into the IDF. In this case, a coalition majority is working to enact arrangements not supported by a large majority of the public – while the public feels that these arrangements are motivated by a desire to maintain the parliamentary majority, even if this undermines the best interests of the state and of Israeli society.

Certainly, a government need not make all of its decisions based on public opinion, but it should define national objectives and strive to realize them even when it faces public opposition. Still, an ongoing gap between how the government conducts itself and public sentiment exacerbates societal tensions, makes it hard to debate important issues effectively, and undermines the overall stability of the political system. This situation is one of the reasons why a majority of the Israeli public has long been calling for early elections, and why a sizeable group of Israelis feel that the continuation of the current government under the conditions that have emerged – especially since the outbreak of the war – is illegitimate.

Against the backdrop of the tumultuous tenure of the current government, the grievous failure to prevent the October 7 attack, the deep social crisis, and the gravity of the issues on the national agenda, there is a widespread belief among the Israeli public that the next elections will be fateful for Israel in two interlinked respects:

- Whether the election results will allow the formation of a government that enjoys the confidence and trust of a broader segment of the public, and that represents what can reasonably be considered as the majority view of Israelis on key national issues.

- Whether, in the wake of the elections, it will be possible to gradually ease social tensions and to reduce polarization. Such outcomes are necessary for stabilizing the system; without them, the social crisis will likely intensify into a dangerous rupture. A reduction in tension and polarization may also facilitate a codified regulatory apparatus for the Israeli political system that could prevent recurring crises of the kind Israel is now experiencing.

The Haredi (ultra-Orthodox) Challenge: A New Opportunity

The summer of 2025 brought the controversy over the IDF conscription of Haredi youth back into sharp focus. The governing coalition sought to legislate a Haredi draft exemption capable of withstanding judicial review (Israel’s Supreme Court struck down a different law two years earlier) and to block the imposition of economic sanctions on draft-eligible men who fail to enlist. At the same time, agreeing over legislation of this kind in wartime encountered difficulty, given the forceful and vocal opposition of hundreds of thousands of soldiers and their families to an arrangement that would perpetuate the IDF draft exemption for tens of thousands of Haredi men.

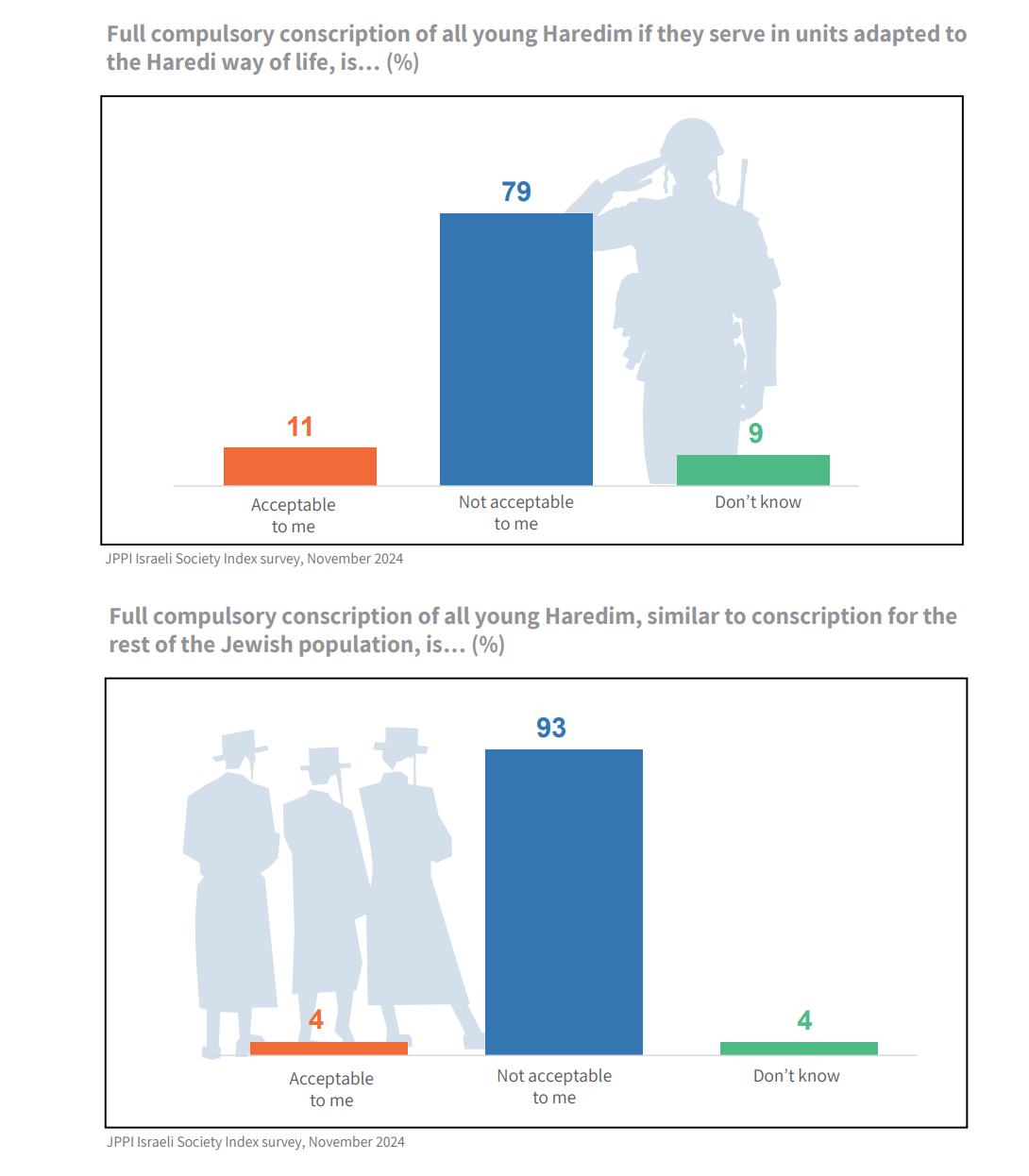

The crisis ensued following two major developments. The first was a Supreme Court ruling that nullified the torato umanuto (“Torah study as profession”) arrangement that had been in place in Israel. The second was the outbreak of the war and its heavy toll on Israeli society. In the war’s early weeks, there was widespread hope and speculation that, given the severity of the security crisis, the Haredi community’s attitude toward the IDF service obligation would shift. But no such shift occurred. The Haredi leadership did not budge from their oppositional stance to the conscription of a large majority of young yeshiva students. In December 2024, a broad JPPI survey of the Israeli society found that even the Haredi public itself had not changed its views. An overwhelming majority – 93% – objected to Haredi men being subject to the compulsory conscription that applies to Israel’s other Jewish subgroups. Only 1% of Haredi respondents said that mandatory enlistment was acceptable to them. More than 85% of the ultra-Orthodox sector, across all its factions, opposed full Haredi military service.

Further, 79% of the Haredi public opposed military service even in units tailored to their way of life. Civilian national service in Haredi frameworks, such as ZAKA and United Hatzalah, was also rejected. The Haredi public’s confidence in the IDF senior command is very low, which fuels their refusal to serve in any security-related state framework. Most ultra-Orthodox Israelis feel that the war will not lead to greater Haredi integration into the broader Israeli society.

Demographics and Strategic Pressure

At the end of 2024, Israel’s ultra-Orthodox numbered 1.39 million – 13.9% of the country’s population. This group has the highest demographic growth rate in the West: 4% per year, compared to 1.4% among the general Jewish population. The Haredi fertility rate is high (6.4 children per woman) – and the community’s population is therefore very young – half are under the age of 16. If these trends persist, in 2030 the ultra-Orthodox will constitute 16% of Israel’s population, and in 2065 they will constitute 32% of the population, and 40% of all Jewish Israelis.

IDF representatives have, over the past year, repeatedly conveyed the army’s immediate needs for maintaining national security. The IDF requires an additional 10,000 combat soldiers. Given the Haredi sector’s rapid growth, and the large number of draft-eligible men who do not enlist, non-Haredi Israelis are forced to bear a heavy burden of regular service and reserve duty. Already today, there are some 15,000 young Haredi men in every conscription cycle – about 10% of each cycle. The number of 18-26-year-olds eligible for the exemption has surged to over 70,000. These figures are quickly rising at a time when the IDF and the State of Israel are working to significantly expand the military in order to prevent another October 7-style attack. As a result, the Haredi conscription debate has shifted from civic equality and burden sharing to urgent national security needs.

This explains the major shift in Israeli public opinion on Haredi conscription. While many Israelis once tolerated the inequality in security burden sharing and tended to believe that increasing the number of Haredi IDF recruits should be effectuated through dialogue and consensus, today the majority of Israelis are unable and unwilling to accept the status quo. And as the debate over Haredi conscription deepens, public awareness of other national challenges posed by the unique character of this community grows – particularly in the socioeconomic sphere. State budgets have provided substantial support for the Haredi way of life – men who do not work, schools that do not equip young people for the modern job market, and dependence on state transfer payments. In essence, the Haredi sector has been subsidized by the tax burden levied on non-Haredi Israelis, which in turn erodes the state’s ability to improve or even maintain the level of services it provides to the Israeli citizenry writ large, in areas such as healthcare, education, and public-use infrastructure.

According to forecasts by economists and social scientists from across the ideological spectrum, if Israel continues along its current trajectory, its standard of living will be comparable to that of the Third World in just two or three decades. Public services will deteriorate, infrastructure will crumble, and it will be hard to maintain the costly and sophisticated security apparatus Israel needs to face military threats.

Since the Tal Law was enacted in 2002, which enabled the continuation of the Haredi draft exemption under certain conditions temporarily (to be revisited every five years), all Israeli governments have tried, by various means, to address the issue of ultra-Orthodox conscription – without success. The Haredi leadership has consistently employed tactics of delay and symbolic compliance to maintain the status quo. Successive governing coalitions allowed this situation to persist in the interest of short-term political calculations. A 2017 Supreme Court ruling nullifying the Tal Law, but no meaningful change followed. For seven years, the Knesset failed to enact an alternative law, and the Supreme Court ultimately determined that in the absence of a valid law, there was no legal justification for maintaining the draft exemption or the continued state funding of yeshivas. The IDF began preparing to draft Haredi recruits – but without legislative backing, and in the face of repeated political obstruction, the effort yielded no meaningful results.

A Window of Opportunity

In the summer of 2025, an opportunity emerged to redefine relations between the state and the Haredi sector. The Haredi community understandably fears for its collective identity – a legitimate concern that should be addressed by designing specialized service frameworks that minimize contact between Haredi draftees and the IDF’s “mainstream.” In light of current circumstances, the Knesset must rise above short-term politics and recognize the strategic importance of the Haredi challenge and the opportunity to initiate a long-needed process to address that challenge.

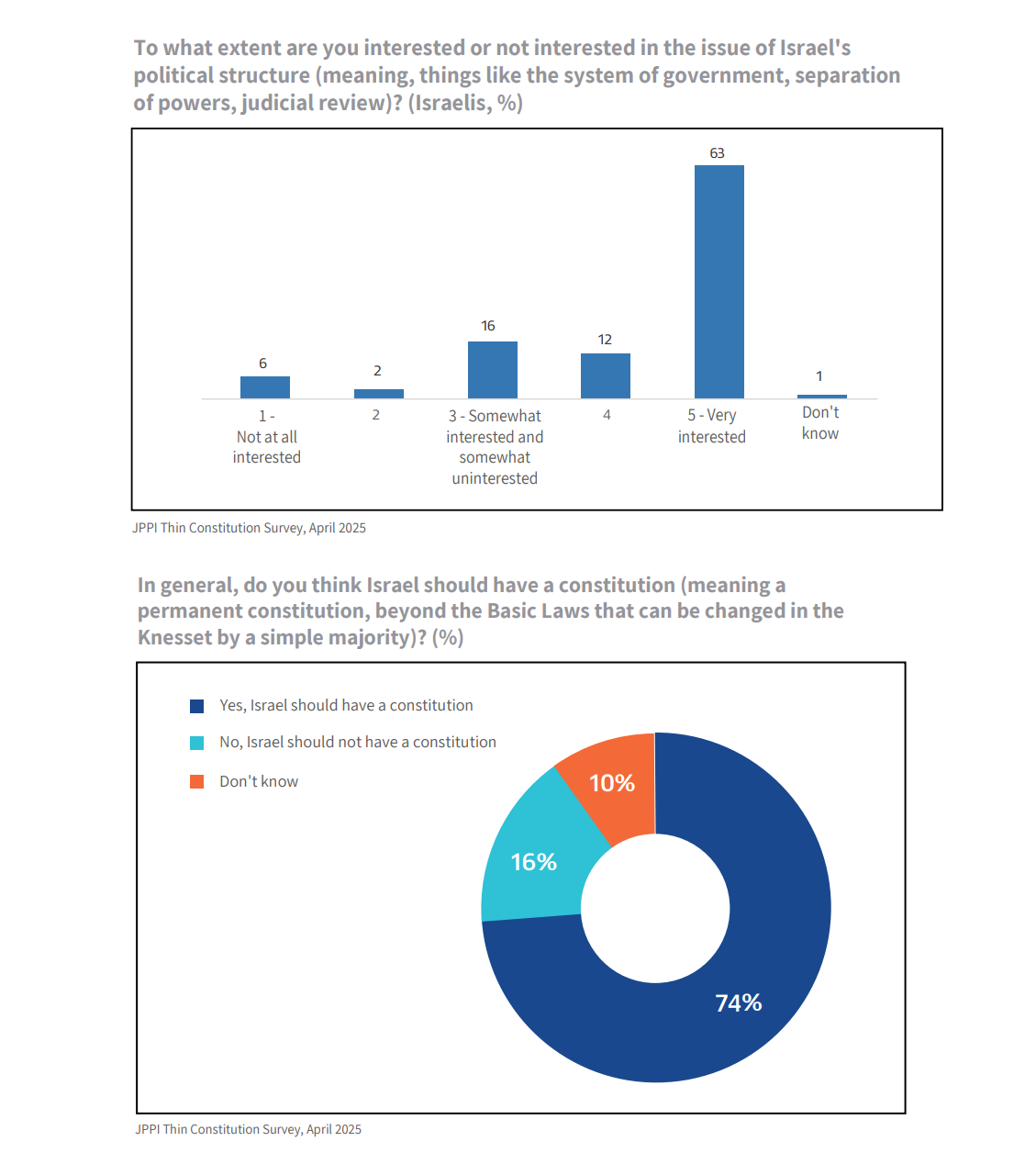

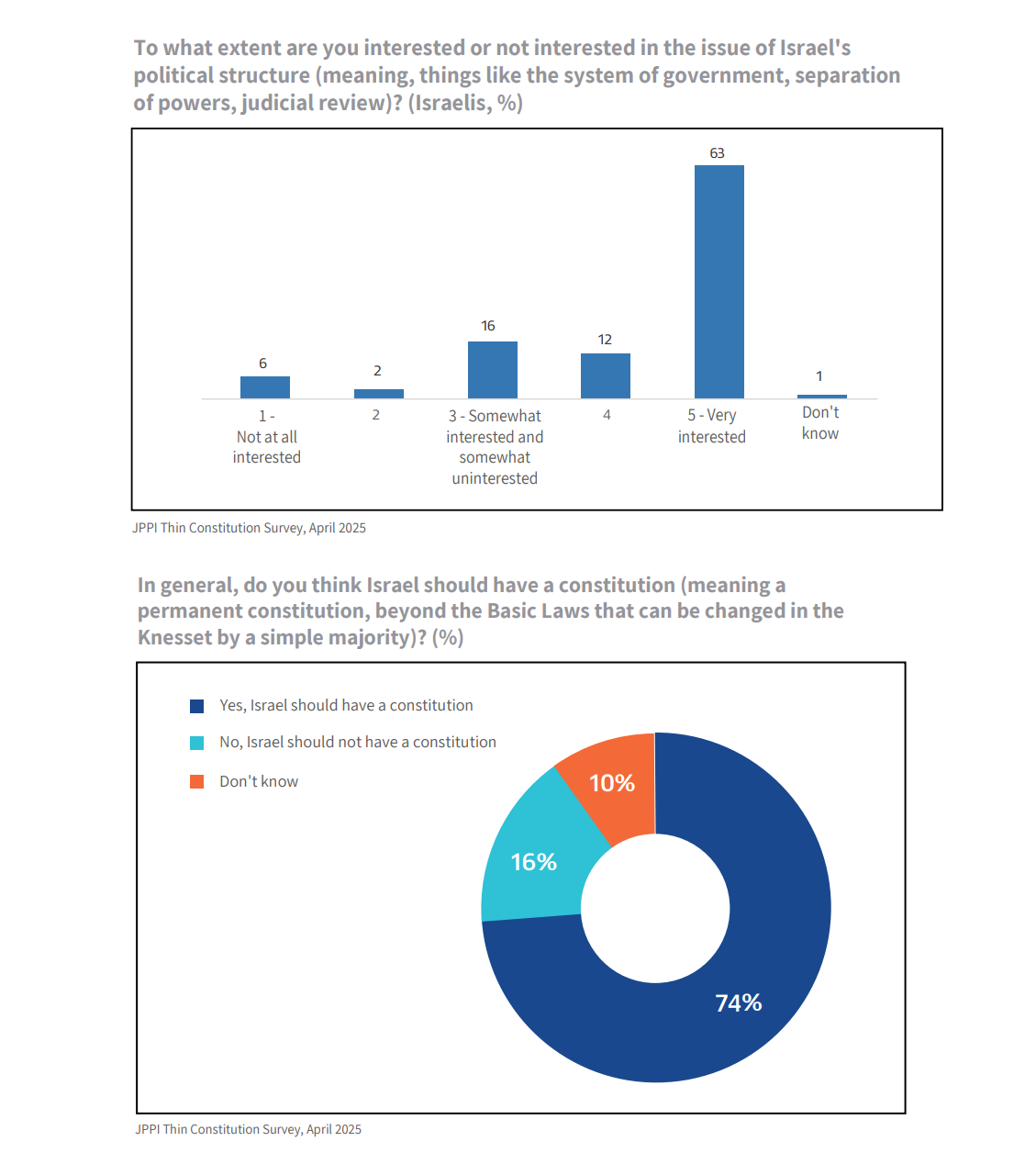

A Thin Constitution: Regulation Without Illusions

David Ben-Gurion, the architect of the State of Israel, designed its governmental structure with considerable attention to the foundational elements necessary for its success under the circumstances of the time. But he and his contemporaries did not provide the constitutional underpinnings of the state. The Declaration of Independence promised that the State of Israel would establish a constitution almost immediately, but this was not done. Historians of the era have concluded that Ben-Gurion deliberately refrained from establishing a constitution out of the – correct – understanding that a constitutional system would erode his power as prime minister, something he sought to prevent.

Nations typically establish constitutions when a “constitutional moment” has arrived – a unique time in the life of a nation, when most of its people and their representatives prioritize the collective interest over the interests of individual identity groups. Experience shows that such moments usually occur at a nation’s founding or in response to dramatic – often tragic – events that lead to a broad realization of the need to act for the sake of the common good. Ben-Gurion chose not to take advantage of the constitutional moment that attended Israel’s founding. In place of a constitution, Israel relies on 13 “Basic Laws,” which are not a true constitution, both because they only address a narrow range of constitutional issues, and because they are not “entrenched” – meaning a simple Knesset majority can amend or repeal them at will. Over the years, many attempts have been made, inside and outside the Knesset, to rectify the situation and provide Israel with a full, entrenched constitutional text. But these initiatives all failed, apparently because Israel had not yet reached the requisite constitutional moment.

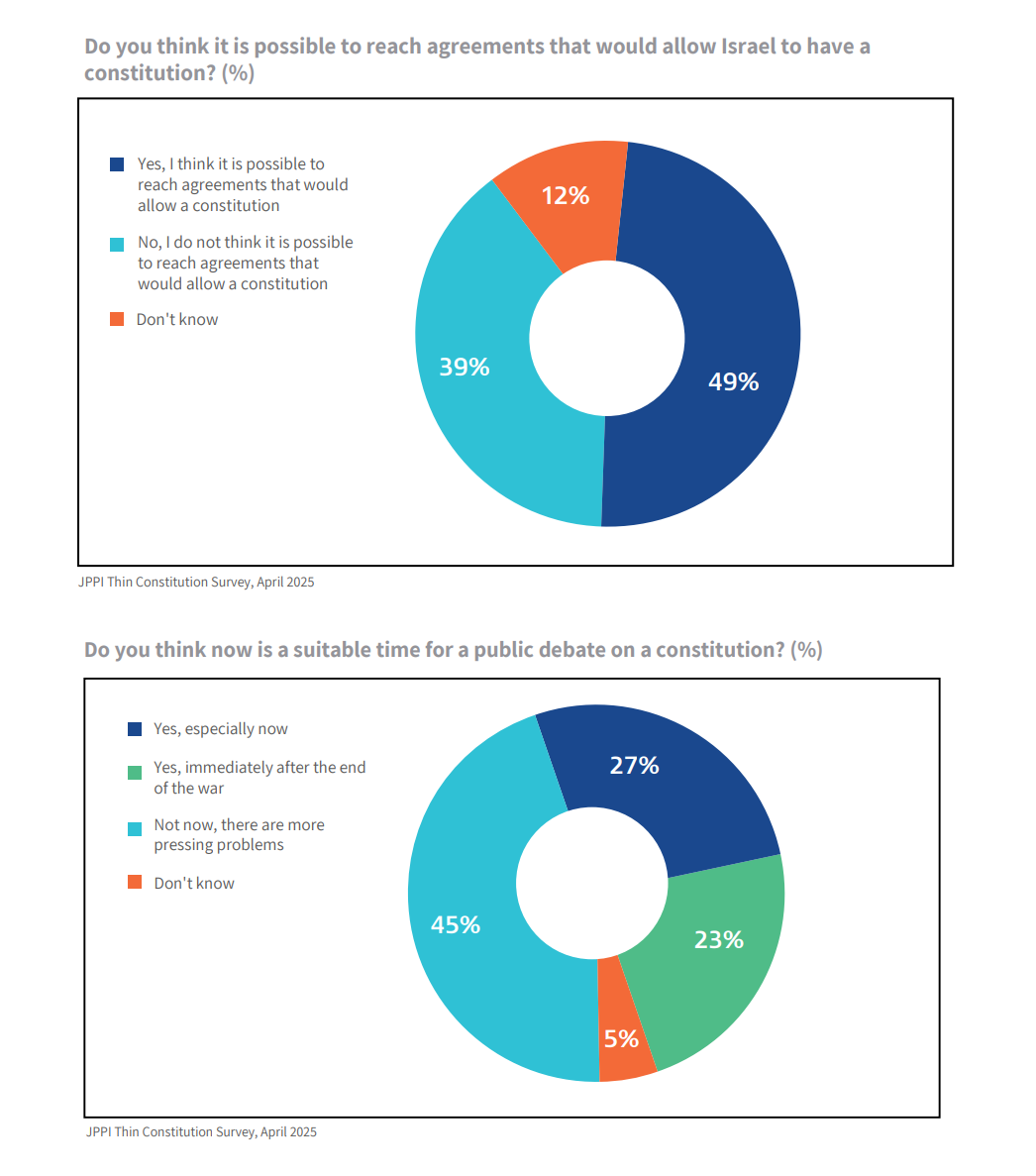

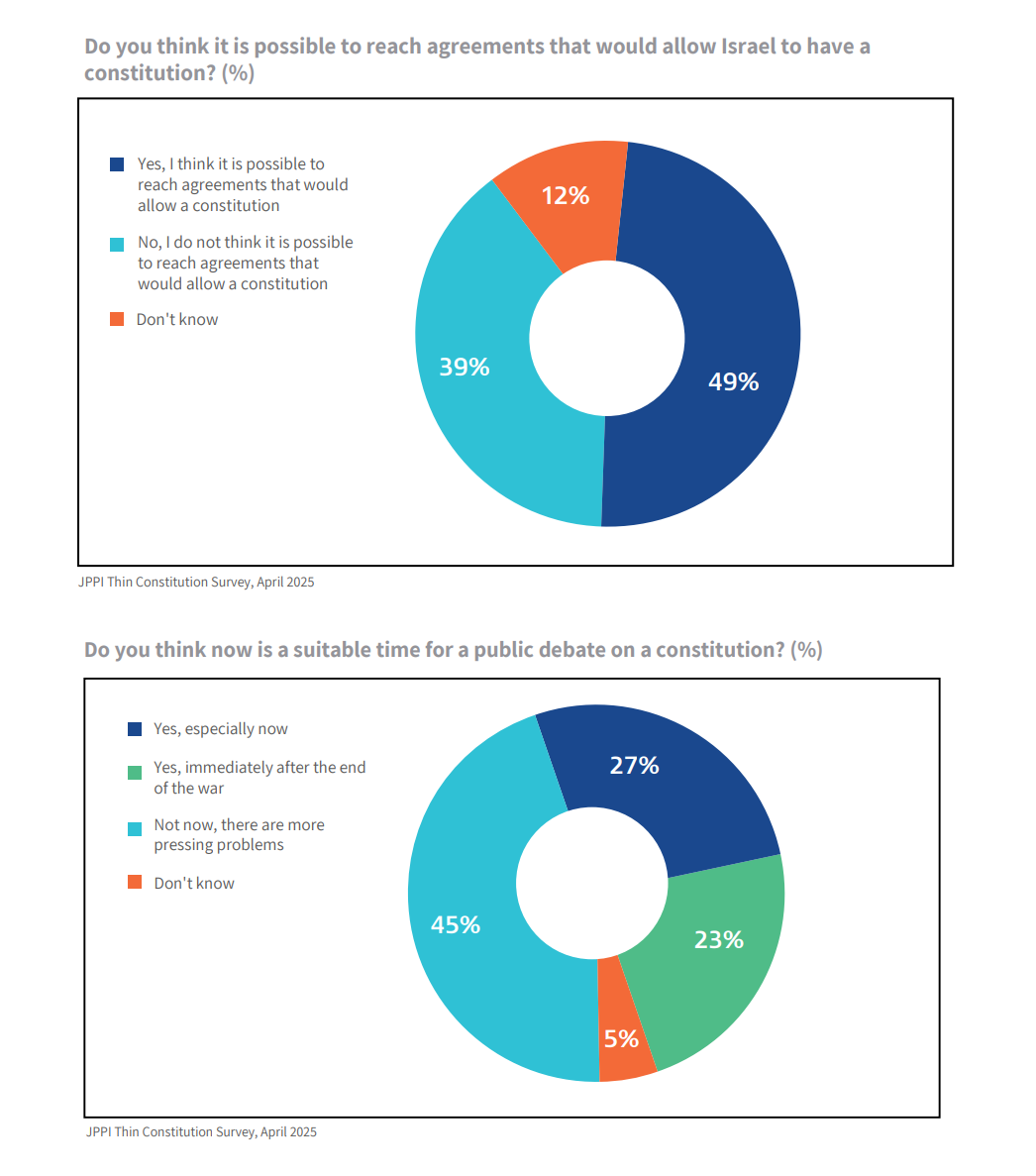

Has the current crisis brought us to such a moment? Should we attempt yet another effort to establish a constitution during the present crisis? The Jewish People Policy Institute offers a cautiously affirmative answer.

We should distinguish between two types of constitution:

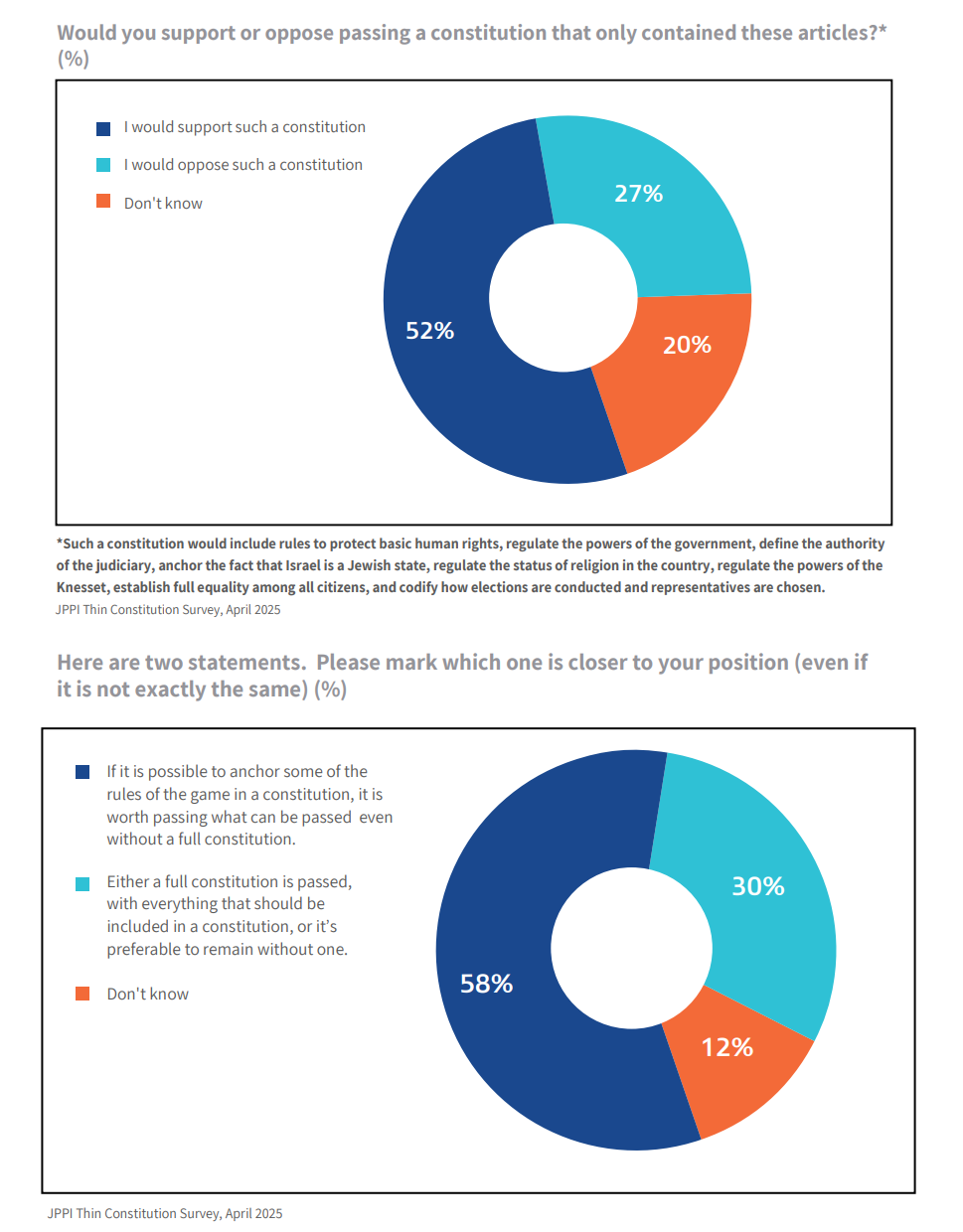

- The first, more common type, is the “full constitution.” A full constitution usually has three parts: (A) an identity section that defines the character of the state; (B) a rights section, including a bill of human rights; and (C) a governmental section that regulates the activity of the branches of government and the relationships among them.

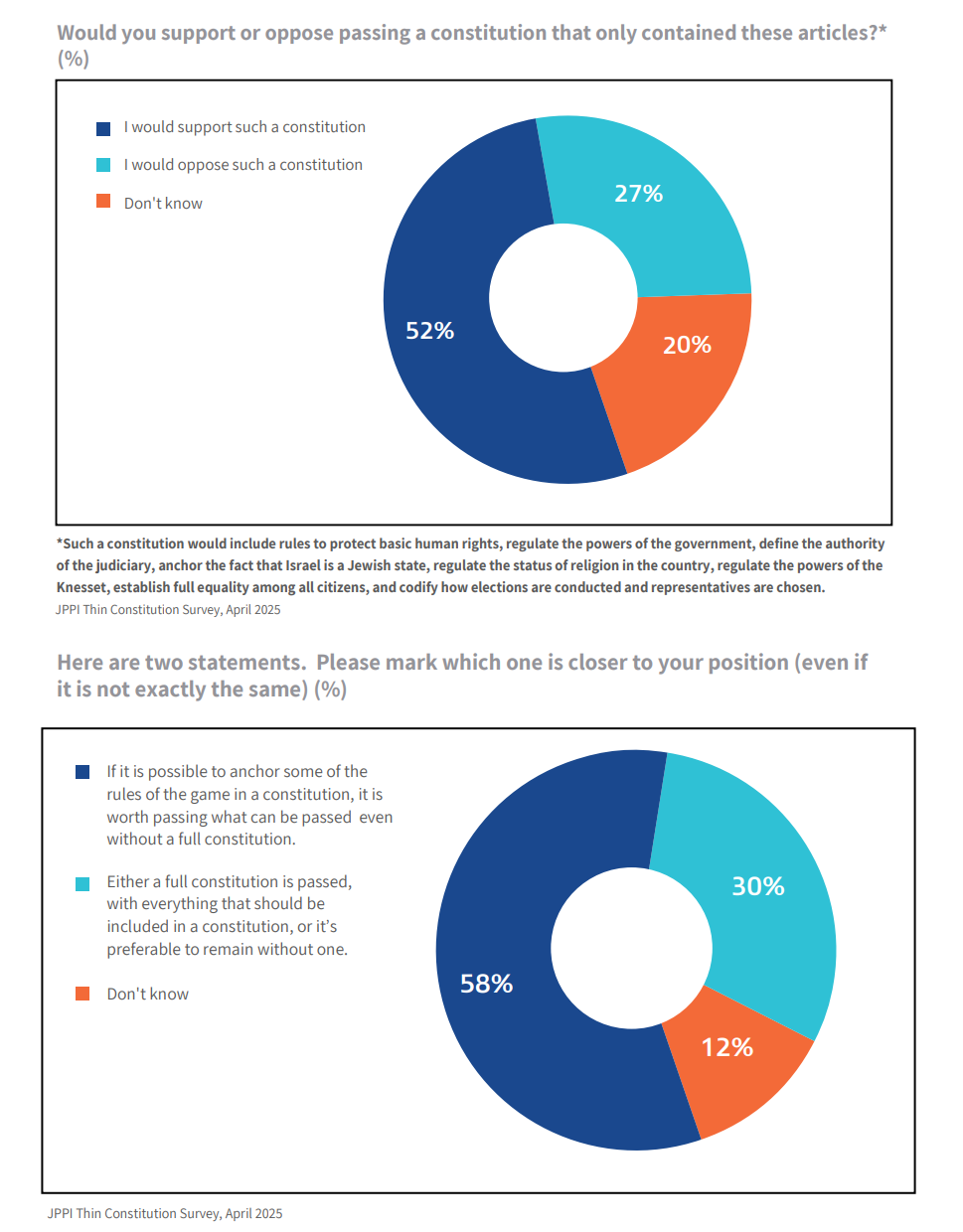

- The second type of constitution, which is less common (though it does exist – in Australia, for instance), is the “thin constitution.” A thin constitution regulates the powers and functioning of government authorities and sets the rules of the political game – it is governance-related rather than ideological or rights-based and does not include an identity component or a bill of human rights.

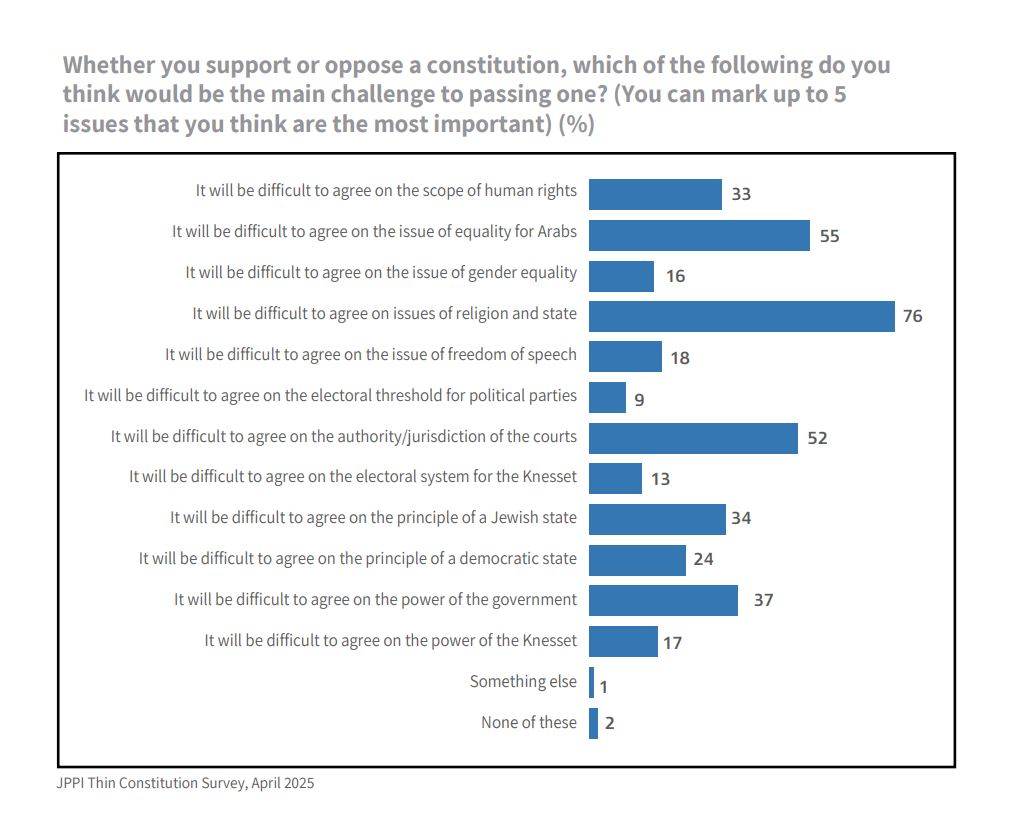

As explained below, contemporary Israel lacks the feasibility of broad consensus regarding the state’s identity and its commitment to a detailed bill of human rights – as normative for a full constitution. However, in JPPI’s view, there is the potential for agreement on regulating the governmental framework of the national system. This would represent a modest constitutional arrangement – hence the term “thin constitution.”

The Israeli Context

In the state’s early years, efforts were made to suppress disputes between different segments of Israeli society. The hegemonic group sought to shape Israeli identity with a social “melting pot” approach. Even after the fire under the melting pot cooled, Israel continued, for decades, to operate as a “consensual democracy” in which, despite the existence of disputes, the country’s central ethos was broadly accepted by most citizens. Due to the urgency of other issues, foundational questions were pushed aside, chiefly the tension between Israel’s particularistic Jewish character and its universalist-democratic character.

In recent decades, however, the identity-based rift between different social groups in Israel has been a basic fact of life that can no longer be ignored. Consensual democracy has been replaced by a “crisis democracy,” where identity politics dominate the main axes of disagreement, based on religion, national lineage, ethnicity, and even geographic location. The fissures in Israeli society have proven chronic and hard to bridge. Israel has found itself in a culture war.

Social tensions dangerously erupted in the wake of the November 2022 elections, when the Minister of Justice Yariv Levin announced a judicial reform that some regarded as a “coup,” fearing that its goal was to settle the culture war in favor of certain of the country’s identity groups – those that form the current coalition.

The far-reaching principles of Levin’s proposal, and the aggressive manner in which it was promoted, led to a crisis. As mentioned earlier, the Israel-Hamas war that erupted in October 2023 refocused national attention, for a time, on security issues, but the fundamental questions regarding Israel’s governance still loom in the background and threaten to erupt once again into a full-fledged crisis.

Proposals for Addressing the Crisis

The fear of a decisive outcome in the culture war – one that would result in the defeat of certain identity groups – has fueled a public debate that has generated various proposals for addressing the crisis.

Some advocate for the establishment of a full constitution. They aim to create a “new social order” anchored in a binding and entrenched constitutional document. Such a constitution would define the nature of the Israeli partnership for generations to come. It would ensure that fringe groups seeking to amplify the state’s Jewish-tribal identity (in its religious and/or national form) or its universalist identity (diluting the nation-state’s particularist character) would be prevented from achieving their aims. A full constitution, defining the state’s identity and ensuring human rights and equality, would draw boundaries for how far radical forces could push their desired change.

Others have proposed different models, including the establishment of a federation. According to this idea, Israel would be reshaped as a system of autonomies, each tailored to one identity group. These autonomous units would cooperate within a federative framework. Each group would manage its affairs according to its preferences in predefined areas, and bear responsibility for its own decisions. This vision would have the Israeli partnership reduced to the minimum necessities, such as collective defense against external threats, without requiring values-based national consensus.

These two proposals represent opposite strategies for responding to Israel’s culture war. A full constitution seeks to consolidate society under a shared framework, while the cantonal approach seeks to acknowledge and institutionalize separation. One is in the spirit of, “All Israel are brothers,” while the other espouses, “Each to their own tent, O Israel.” Still, the proposals have one thing in common: both are highly impractical, and efforts to implement either of them could further inflame the national crisis.

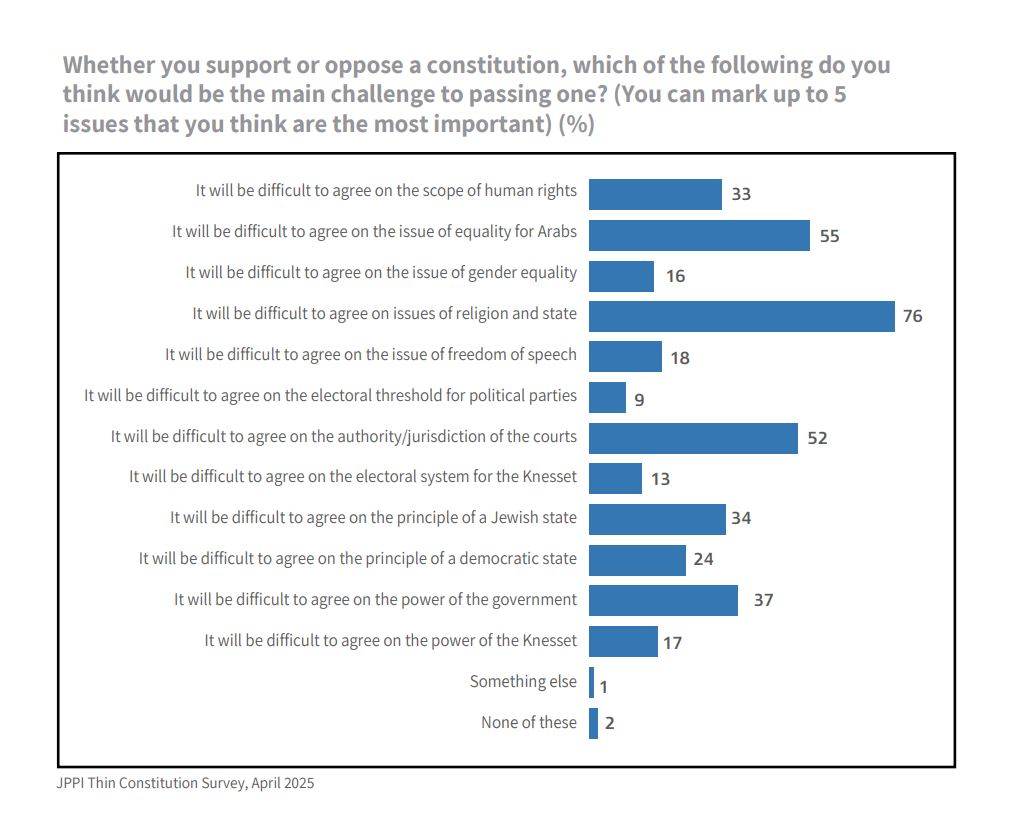

A full constitution is a noble ideal. But amid deep polarization and essential disagreement over the state’s identity, it is hard to envision broad Israeli agreement on such a document. Pursuing this as a political goal could aggravate the social system and push it to a boiling point.

Cantonization, on the other hand, is a bad idea. It would give normative backing and political/institutional legitimacy to Israel’s identity-based division. Instead of managing conflict, it would intensify and institutionalize it. If Israel were to become a “state of all its tribes,” we may assume that the centrifugal forces currently pulling identity groups away from one another would accelerate dramatically. The utopian hope of all the tribes living peacefully side by side under autonomous conditions would shatter in a reality where each tribe is organized independently and legally backed. The resulting competition over control, influence, and ideological narrative would only fortify and extend the barriers already separating Israeli identity groups – ultimately crippling their ability to cooperate in achieving broad national objectives.

Instead of aiming for either a full, unifying constitution or a disuniting cantonization, we ought to work toward a modest but relatively feasible solution: a “thin constitution.”

The Procedural Option

Some of the irrelevant issues are already addressed in existing (some good, some less so) Basic Laws, while other critical issues, such as the legislative process, judicial review, the procedure for appointing judges, and the Supreme Court’s powers – are governed by “ordinary” legislation. However, both approaches (i.e., Israel’s entire governmental-political framework) are on shaky legal ground. Basic Laws can be enacted and amended with a simple Knesset majority, just like ordinary laws, with no special procedural requirements. This is a serious flaw, which puts Israeli democracy on a slippery slope. What is supposed to function as Israel’s de facto constitution is effectively “clay in the hands of the potter” – the Knesset. Basic Laws are easy prey for the whims of any governing coalition that aims to impose sweeping changes – from attenuating the Supreme Court’s authority to limiting the voting rights of certain citizens, to altering the Jewish or democratic character of the state.

Although in recent years the Supreme Court asserted its authority to conduct judicial review of Basic Laws, this was done with the slimmest possible majority, which no longer exists since the panel of justices changed in the past year. If the argument that the Supreme Court lacks a sufficient source of authority to conduct judicial review gains traction (as it likely will), there will be no legal obstacle to a Knesset majority determined to transform Israel at will.

This is not a theoretical concern. All recent Israeli prime ministers, from across the political spectrum, chose to amend the Basic Laws for the sake of their immediate political interests (see also: “rotation government”). Just in the past decade, the Knesset has introduced more modifications to Basic Laws than all the amendments made to the U.S. Constitution since its enactment in 1789. We are treading on thin ice, with no assurance that our political reality will not shift dramatically as a result of a partisan maneuver. The consequences include instability in our public life, intense clashes between the governmental authorities, erosion of public trust in institutions, deepening social polarization that brings the country to the brink of civil war, and an overall diminution of Israeli democracy.

Outside of Israel, in every constitutional democracy, the rules of the game cannot be changed so casually as to only require a simple majority. Due to their importance, the rules are codified in entrenched constitutions, and their modification is subject to strict requirements – e.g., a parliamentary supermajority; approval (in bicameral legislatures) by both legislative houses; approval (in federations) by all or most member states; public referenda; or other stringent means. Further, most countries adhere to a constitutional culture that discourages changing foundational rules for momentary political convenience.

Thin Constitution – A Viable Option

Israel’s social and ideological divides prevent a resolution of the ongoing culture war. However, it does not prevent us from adopting a thin constitution that would provide a stable and agreed-upon framework for managing our disputes.

There is a realistic chance that a broad consensus – say, 75 Knesset members – can be reached on the terms of a thin constitution, precisely because it avoids the values-laden issues at the heart of the culture war.

Currently, the Knesset is perceived as more attuned to the Jewish character of the state, while the judiciary is regarded as more attuned to the state’s liberal values. This is why the present (non-liberal) coalition seeks to transfer the judiciary’s powers to the political branches. But this is a shortsighted calculation, as today’s political conditions are not immutable.

No one can predict who will win the next round of elections or form the next governing coalition. Therefore, all sides have an interest in optimally stabilizing the system, from a collective perspective, since any camp could potentially find itself in the opposition. Rules of the game entrenched in a thin constitution would protect each side.

This is also the case regarding the composition of the Supreme Court. While most of its justices were once classified as liberal, the balance of power is now changing, with half of the bench considered conservative. If the current method for selecting the Supreme Court’s chief justice remains unchanged, in a few years a conservative judge will head that august body. A relevant analogy can be seen in the U.S. Supreme Court, which has transformed dramatically in recent years to become a stronghold of American conservatism. There is no reason to assume that something of the kind could not occur in Israel.

This uncertainty offers an excellent basis for reaching contemporary constitutional agreements on entrenched rules of the game free of a priori ideological preferences. Behind a “veil of ignorance,” to use John Rawls’s term, the issue of separation of powers and the complex dynamics between the branches bears no relation to the views of the opposing parties in the culture war. It would benefit everyone, across the political and cultural divides, if entrenched rules of the game were entrenched to properly balance government authorities. We all have a common interest in shoring up the institutional structures of governance, which will serve as a safe harbor when we inevitably find ourselves in the minority.

It is important to note that even a full constitution is “only” a social document. It cannot in and of itself, dictate social outcomes for a society unwilling to accept the agreements and values enshrined within it. Yet, despite its limitations, there is no better instrument in the democratic toolbox for regulating governance than a constitution.

That said, insisting on a full constitution that is unattainable at this time could prove dangerous. Those who demand “all or nothing” risk forfeiting the option of a thin constitution: a modest option relative to what is desirable, but an ambitious one relative to the current situation. A thin constitution would define, for generations, the rules of the game for sane conduct in an era of polarization, in the midst of a culture war, without descending into civil war.

In line with this assessment, JPPI has invested considerable effort over the past two years in formulating a thin constitution to represent a broad consensus. This work is set to conclude in late 2025 and will be presented as a foundation for constitutional agreements on entrenched rules of the game free from ideological bias.

Conclusion

The past three years have been emotionally, economically, and militarily difficult for Israelis. Nevertheless, the convergence of crises – in the political, social, and security spheres –also presents a rare opportunity to fundamentally change a number of entrenched norms. Just as Israel must now reassess its military structure, budget, size, and mission scope, it must also tackle the non-military domestic challenges that vex it as a society and threaten its internal cohesion are no less grave than external threats. Reevaluating Israel’s coalition framework, revisiting its constitutional structure, and addressing its daunting social challenges, most notably the Haredi question, are equally critical for Israel’s renewal and its emergence from crisis.