Immigration to Israel Post-October 7

For Israel, immigration, or aliyah (ascent), is a central pillar of Zionism and a governmental and budgetary priority. Conversely, emigration, traditionally termed yerida (descent), has been a cause for national concern, with leaders from Ben-Gurion to Rabin expressing themselves in the strongest terms on the issue. The significance of migration is particularly apparent in times of war. Streams of Israelis rushing to return home in wartime are taken as a sign of national solidarity, while emigration due to ongoing conflict makes the headlines.

Israel’s history has been shaped by immigration, both in the pre- and post-state eras. Notwithstanding the national narrative, the timing and flow of migration into Israel has been primarily determined by push factors in the country of origin, rather than developments in Israel. Most recently, this effect has been seen in the sharp rise in the number of immigrants from Ukraine in the wake of its war with Russia. However, over the years, there have been smaller increases in the aliyah rate, such as following the Six-Day War, prompted by events inside Israel.

The Current Conflict and Immigration to Israel

This chapter analyzes the impact of the current conflict on rates of immigration to Israel. Has there been an increase in immigration to Israel following the outbreak of hostilities on October 7, or is Israel now perceived as too dangerous, resulting in lower immigration rates? Emigration from Israel is much harder to measure with any degree of accuracy, as it does not require an official change of status and, therefore, will not be included in this analysis.

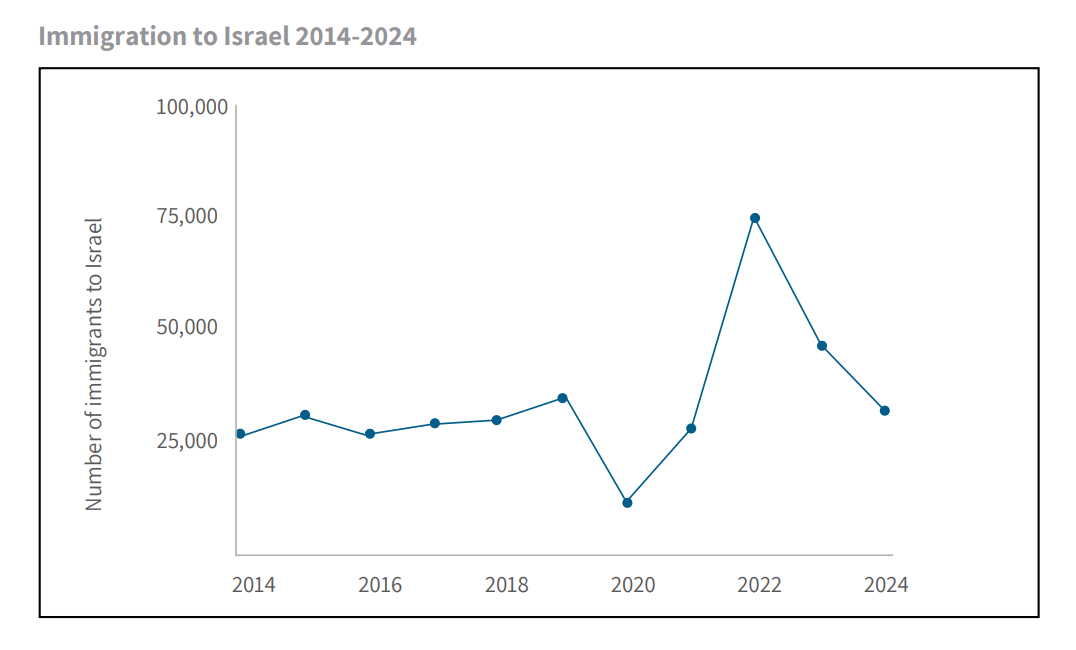

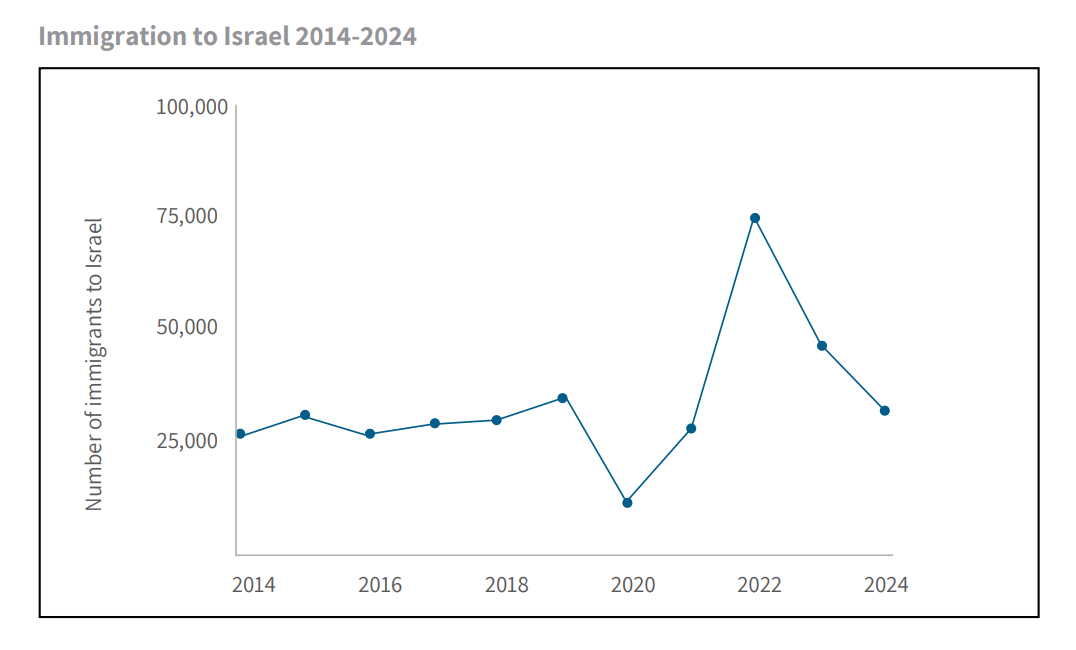

An initial look at the overall number of new immigrants arriving in Israel in the last few years would suggest that the war that ensued after the events of October 7 had a huge negative impact on immigration. The number of immigrants halved between 2022 and 2024. In 2024, only 32,161 immigrants came to live in Israel, compared to 46,590 in 2023 (the year war broke out) and 74,474 in 2022. However, on closer inspection, it becomes clear that the war was not the determining factor of this admittedly dramatic drop, as most of the decline occurred before the war broke out in October 2023. In fact, the high immigration numbers of 2022 and 2023 are the true outliers; the 2024 figures are closer to the average for the last decade. These higher numbers are likely due to a combination of post-pandemic effects and the Russia-Ukraine war.

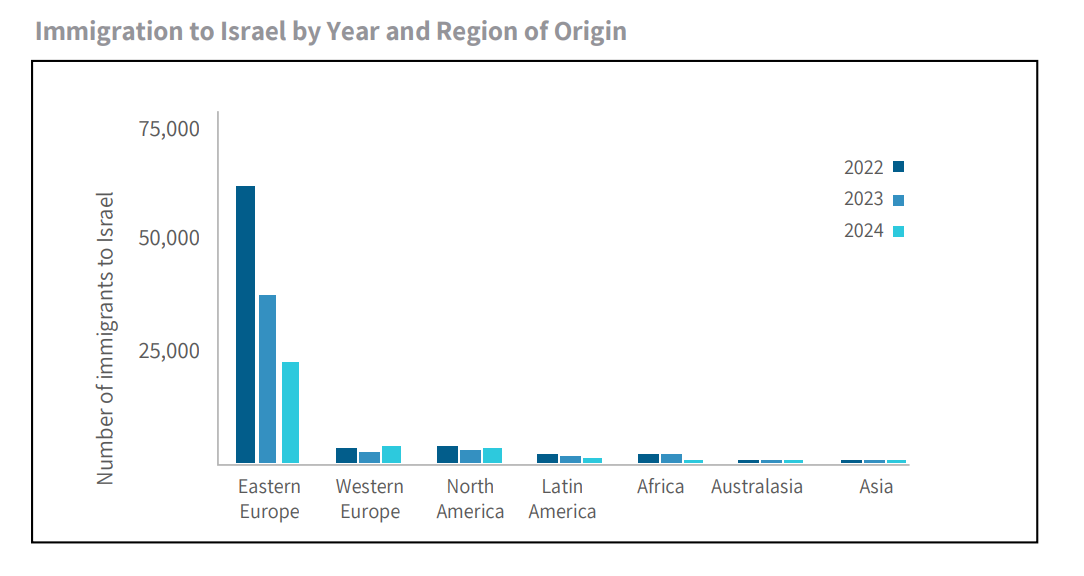

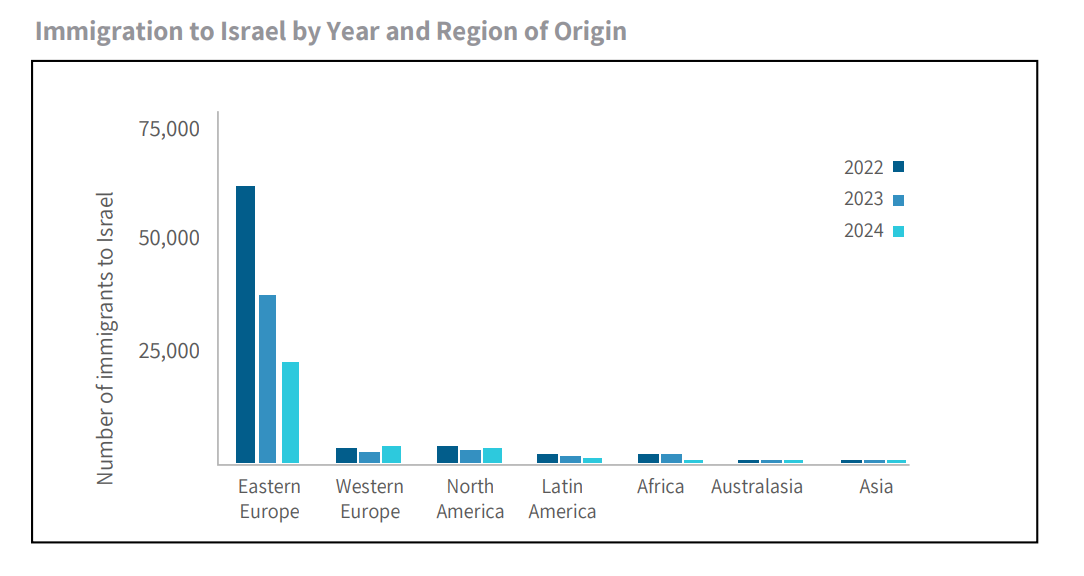

Looking more closely at the data by immigrants’ region of origin is more instructive. By far the largest number of immigrants in the period 2022-24 came from Eastern Europe, specifically Russia and Ukraine. Shifting migration patterns among this group are primarily responsible for the changes illustrated in the graph of overall migration rates. Fluctuations in migration are more attributable to developments in the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war than to events in Israel. Further, the data indicate that migration patterns to Israel vary significantly by region, each of which must be analyzed separately to isolate the effects of the Israel-Hamas war on migration to Israel.

As the graph shows, the pattern found for migration from Eastern Europe is not replicated in Western Europe and North America, where there was a decline in migration to Israel in 2023, but levels recovered or even outpaced the 2022 rate in 2024. This may be the result of planned migration from the last few months of 2023 being delayed until 2024 or from a shift in migration patterns. Closer inspection of migration data will show which it is.

Immigration from Latin America and Africa followed a pattern similar to that of Eastern Europe, declining in 2024 and in some cases also in 2023. It appears that the war deterred migration only among those seeking to improve their quality of life. Thus, immigration from Western Europe and North America recovered quickly as the migration calculus was not affected by the war because their impetus for moving to Israel was not to improve living standards. However, for those in Africa and Latin America, it appears that Israel has become a less attractive destination due to the conflict. Migration from Eastern Europe may have been affected by similar concerns but seems mostly determined by developments in the conflict between Russia and Ukraine.

War and Migration to Israel

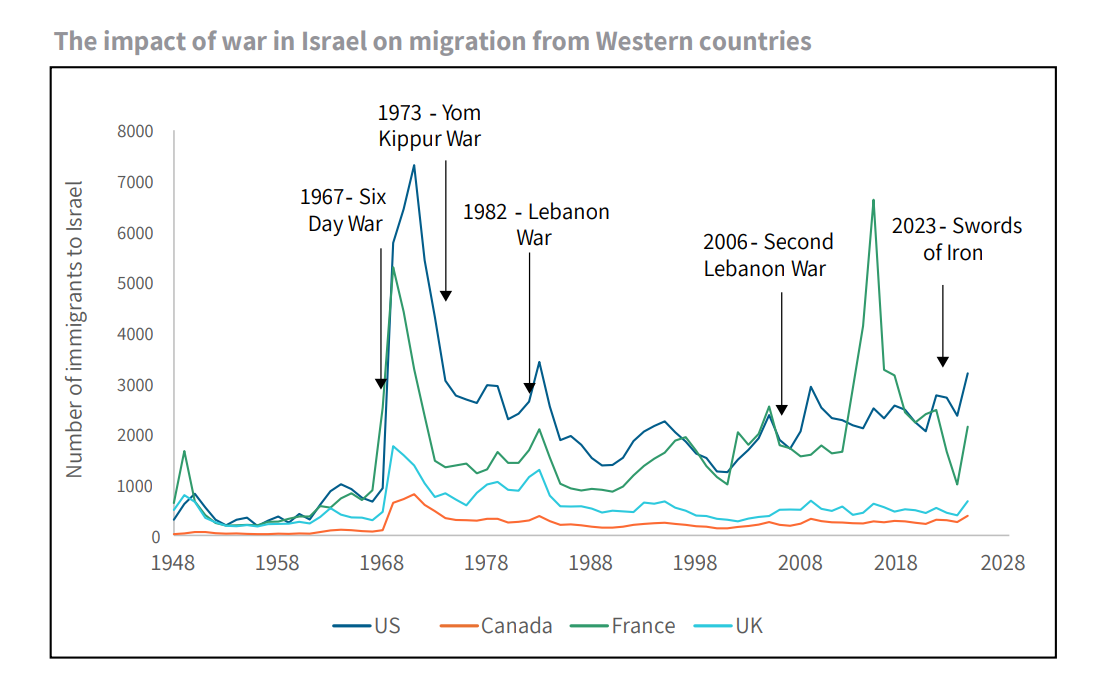

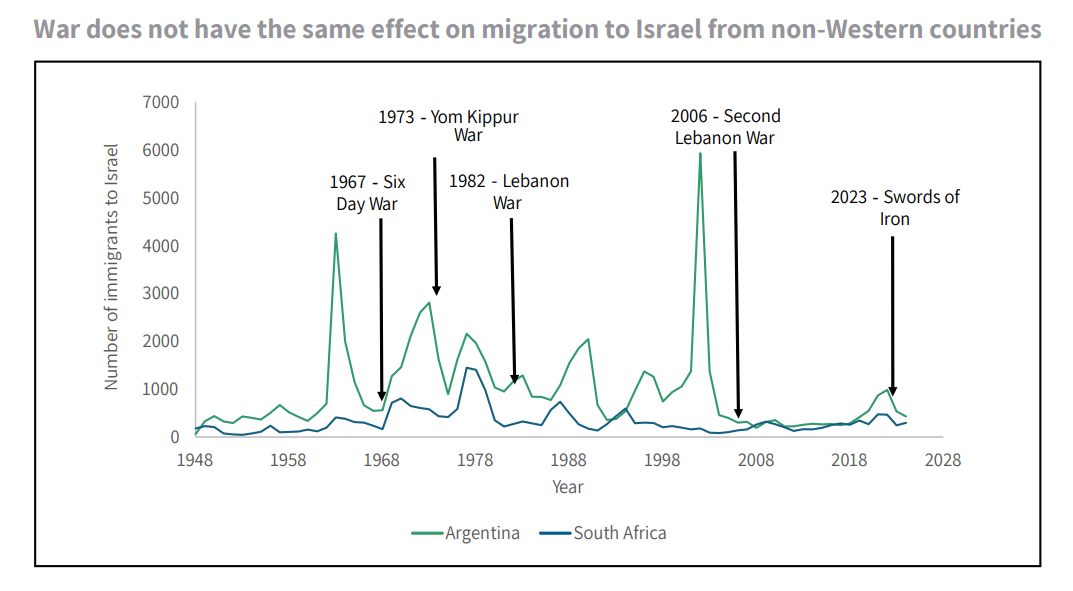

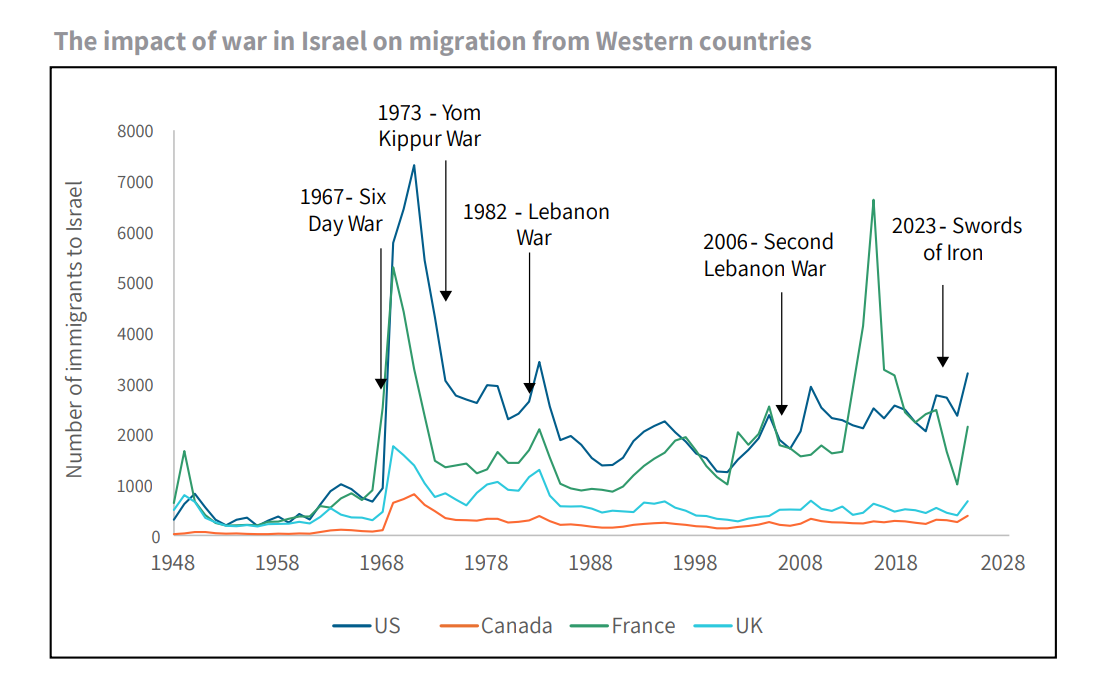

There are precedents for increased migration to Israel from Western Europe and North America after a war. The most marked and well-known example of this is the sharp increase of migration to Israel from Western countries in the years following the Six-Day War. This pattern was repeated after the Lebanon War in 1982, but not after the Yom Kippur War or the Second Lebanon War.

There was a clear increase in migration from the United States, Canada, France, and the UK following the outbreak of the current conflict. Not only are these countries representative of trends in Jewish communities in Western Europe, they are home to the four largest concentrations of Jews outside of Israel and together constitute almost nine-tenths of the Jewish Diaspora population.

The response to the post-October 7 conflict is an increased desire to live in Israel. As in the past, when Israel faces acute danger, some Jews in Western countries feel the need to uproot themselves and move to Israel. It may also be that the spike in antisemitism in the aftermath of the October 7 attacks led many to reconsider their place in their home societies and decide to relocate to Israel. Certainly, it appears that the uptick in migration to Israel is greatest for France, the community that has traditionally seen sharp increases in aliyah rates due to the increasing incidence of antisemitism.

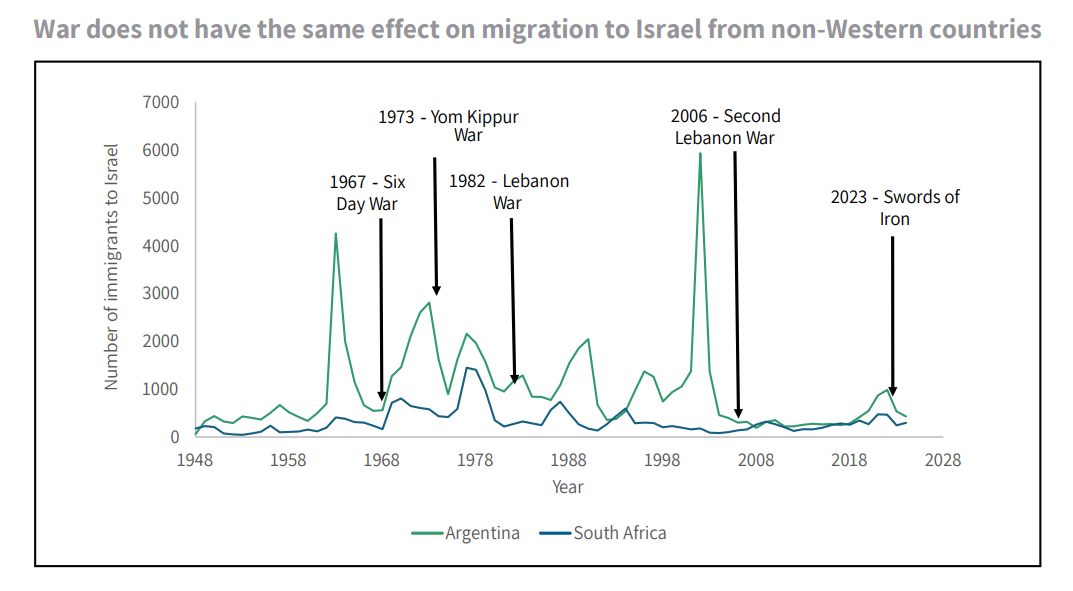

The relationship between war in Israel and migration to Israel from other regions looks quite different. War in Israel does not have a sharp positive impact on their migration rates. There are signs of increased immigration after the Six-Day War, although this effect is somewhat delayed and so may be attributable to other causes. There was a small increase in migration to Israel from South Africa in 2024, which may be due to the war or may just be indicative of the kind of fluctuation seen every year, whereas Argentina saw fewer people move to Israel in 2024 than in the previous year. Migration flows appear to be primarily determined by local events and the desire to leave their own country, rather than by a sense of heightened solidarity as a result of the outbreak of war in Israel.

Eastern European countries are not included in this graph as for most of the period, emigration was tightly restricted by the authorities. Data from the last two years suggest that the current conflict has decreased migration across Eastern Europe, except for more affluent states such as Czechia and Lithuania. This reinforces the notion that for those living in countries with a strong economy and a high standard of living, migration to Israel is not motivated by the desire for a better life that characterizes much of global migration patterns. Rather, it is generally a result of ideological motivations that lead people to want to live in Israel, although it may also be a response to antisemitic sentiment in their home country.

The decrease in migration to Israel from Argentina in 2024 is mirrored across Latin America. Previous research has documented the alignment of peaks in immigration from Argentina with periods of economic instability, providing further support for the notion that migration from the region is primarily economic in motivation, although the choice of Israel as a destination may be influenced by ideological as well as practical concerns, such as ease of gaining citizenship and generous economic benefits for immigrants. As South Africa is by far the largest Jewish community in Africa, it is hard to generalize trends across the continent. For instance, Ethiopia contains the other large concentration of Jews in Africa, but rates of migration to Israel reflect Israeli governmental policy, rather than the preferences of individual Ethiopian Jews. However, the general trend of reduced migration to Israel after October 7 can be seen across Latin America, the Former Soviet Union, South Africa, and the poorer East European states, in sharp contrast to trends for North America, more affluent European countries, and Australia, where migration to Israel increased.

In sum, migration to Israel from affluent countries is generally ideologically motivated, rather than by a desire to improve standard of living and avoid crises and conflicts. Therefore, war in Israel increases immigration to Israel. However, immigration from Latin America, Africa, and much of Eastern Europe appears to be primarily driven by a desire to escape difficult economic and security conditions. As a result, conflict in Israel has a negative effect on the aliyah rate from these regions.

Delayed Migration

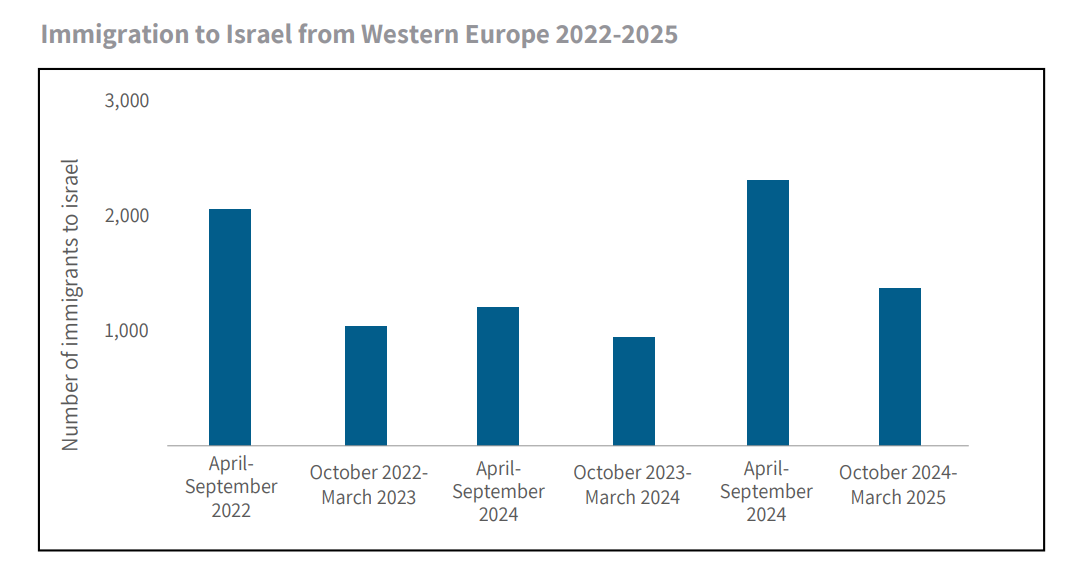

Focusing more narrowly on migration from Western Europe and North America, it is possible that the apparent increase in migration to Israel after October 7 is really just delayed migration, i.e., people who planned to move to Israel in the last few months of 2023 but postponed their aliyah and arrived in 2024. Is the impact of the war limited to the timing of migration to Israel from the West, or does it reflect a real increase in response to events in Israel?

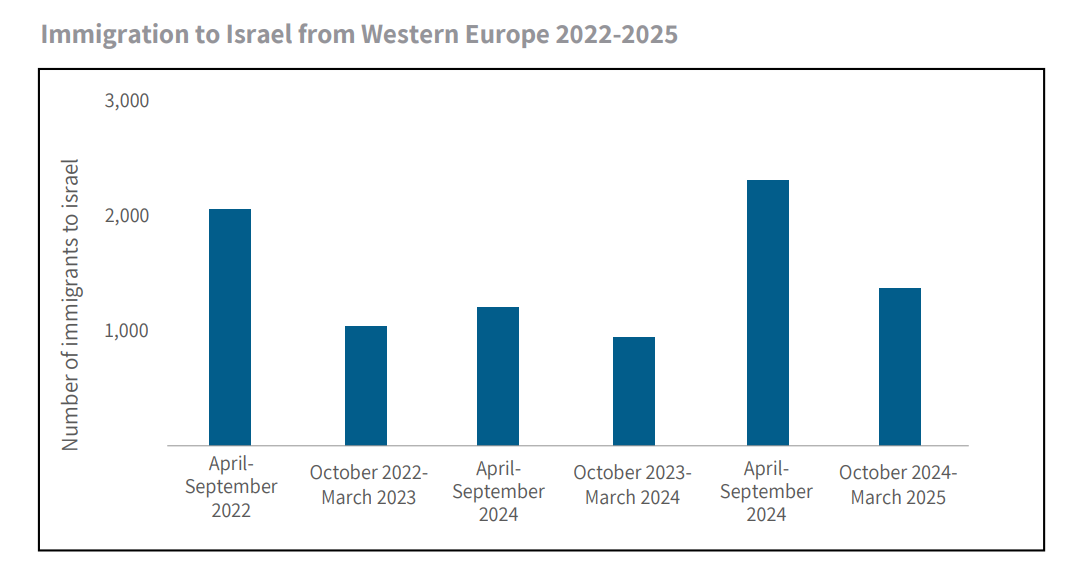

Given that war broke out in October, and there is generally less migration to Israel from Western countries in the last quarter of the year, it is unlikely that postponed migration explains the spike in immigration in 2024. However, it is possible to check the data by breaking it down into six-month increments to compare migration in the months April – September 2022, October 2022 – March 2023, April 2023 – September 2023, October 2023 – March 2024, April 2024 – September 2024, and October 2024 – March 2025. This analysis will establish the effects of the war on migration beyond the initial shock and technical difficulties, which may have led to a decline in immigration in late 2023 and a bounce back in 2024.

There are some important things to note. First, the lower rate of immigration in 2023 was not due to the outbreak of war. Immigration was much lower in the period between April and September 2023 than it had been in the previous year. This may be because the 2022 rate reflects an unusually high number, including much postponed migration that resulted from the global COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021. Alternatively, it may have been a response to the political crisis in Israel.

Second, the huge increase in immigration rates in the interval between April 2024 and March 2025 suggests a real change in attitudes, rather than just the fulfillment of postponed migration. Further, the rate of immigration from Western Europe in the period October 2023 to March 2024 was similar to that recorded in the same period a year earlier, despite the lower migration rate in the six months prior, suggesting that delayed migration is not a significant factor and that the rising rates of migration to Israel in this period reflect a post-war spike in immigration, similar to those that were seen in the past after the Six-Day War and other conflicts.

Conclusion

The impact of the Israel-Hamas war on migration to Israel has been significant. For those living in affluent states in North America, Europe, and Australasia, the war has led to a spike in migration to Israel. Whether this is due to an increased sense of solidarity with Israel, enhanced Jewish identity, or the rise in antisemitism seen since October 7 cannot be deduced from the available data. On the other hand, the war seems to have depressed immigration rates from poorer countries, where migration decisions are primarily related to escaping poverty and instability. For them, Israel in wartime is seen as a less desirable place to live.