The Geopolitical Landscape – 2025

Nearly two years after the October 7 massacre, a dark shadow continues to loom over Israel’s security and strategic situation. Developments that began with Hamas’s murderous attack have shaken Israel and the entire Middle East. They set off a series of dramatic events that included the first direct war between Israel and Iran, a severe Israeli-American strike on Iran’s nuclear program, and a resounding military defeat of Hezbollah in Lebanon. Notably, these events also led, indirectly, to the collapse of the Assad regime in Syria, nearly 14 years after its civil war began.

A new regional power alignment is now taking shape. There can be no doubt that the radical Shi’ite axis led by Iran has lost stature, but this is not yet a decisive victory, nor are there any signs of regime collapse in Tehran, despite the harsh and unexpected blow it suffered. The complementary developments American and Israeli leaders were hoping for – a reinforcement of the strategic alliance between Israel and several conservative Sunni states, first and foremost Saudi Arabia – have not yet been realized.

One clear change has occurred in Israel’s policy: unlike in the past, Israel no longer waits for a threat to materialize near its borders but strikes almost immediately, making clear that it will not tolerate new threats. Signs of this approach could be seen over the last year on the Syrian and Lebanese borders – after a ceasefire with Hezbollah was announced and after the regime change in Damascus.

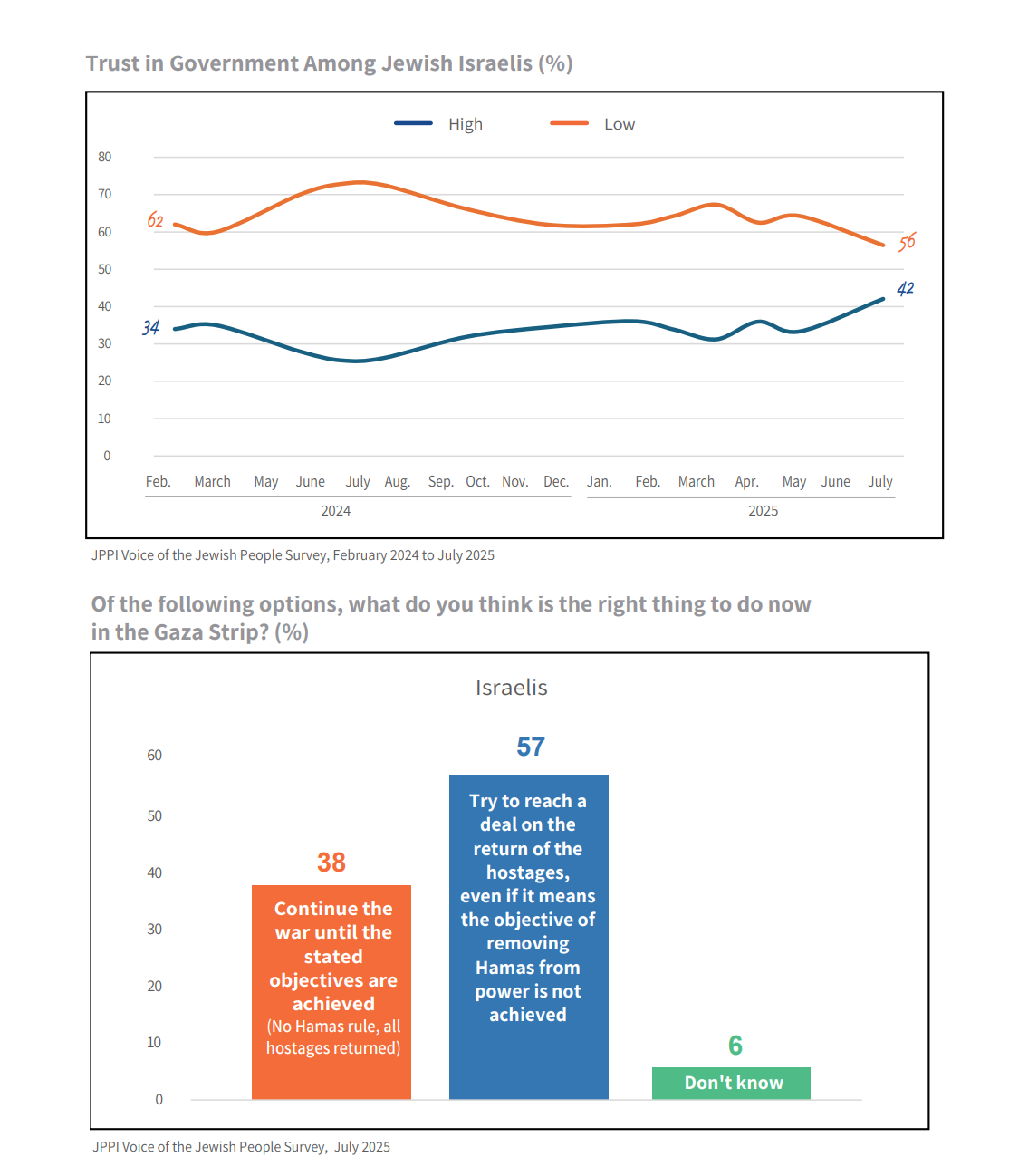

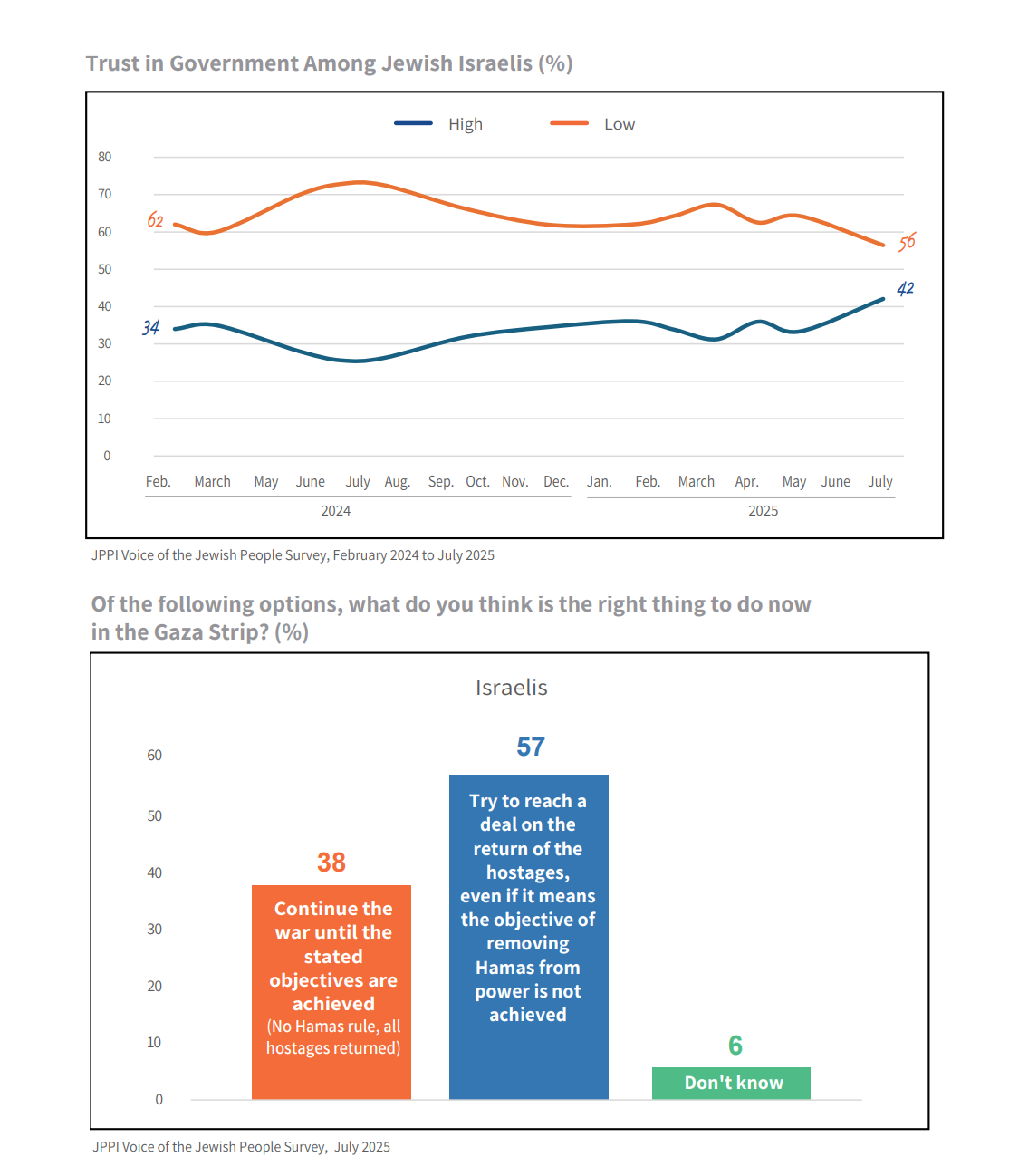

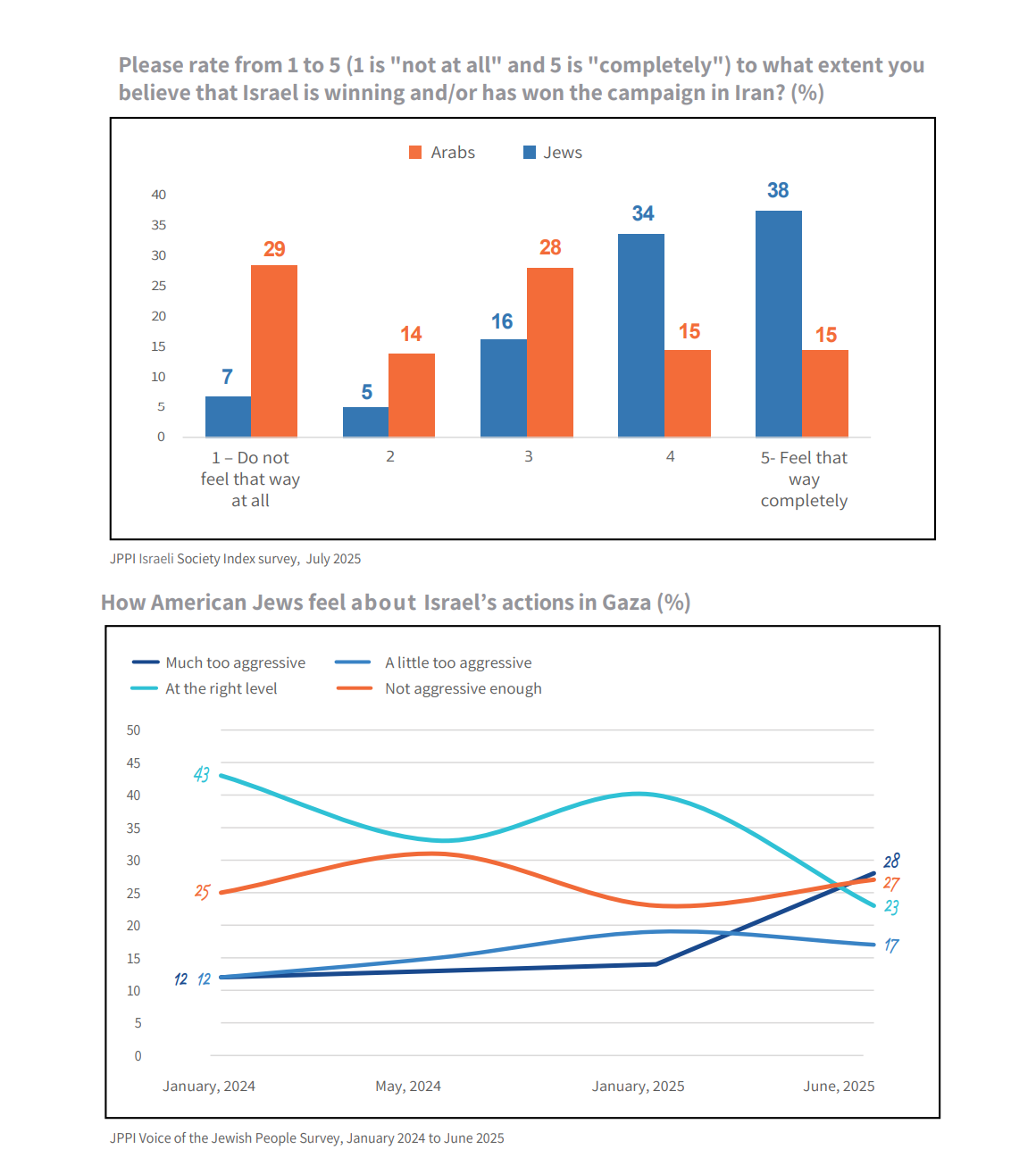

But no less significant is the hard fact that the Gaza situation remains unresolved. As of this writing, in September 2025, Israel has not achieved its two primary declared objectives in the Gaza war: the return of all the hostages taken on October 7 (living or dead); and the toppling of Hamas rule in the Strip. The bloody war in Gaza – the longest in Israel’s history – continues to stir fierce debate within Israeli society, along with growing criticism of the government’s performance and positions. The prolonged delay in returning the hostages has become a deep social wound, driving intensifying discord over government policy. At the same time, Israel’s extensive use of force, accompanied by massive civilian casualties and a large-scale humanitarian disaster in Gaza, has led to unprecedented international isolation.

After the success in Iran, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu attempted to launch a new narrative. He now claims that in the early days following the massacre, he vowed to establish a new regional order that would reshape the Middle East (such things were said, according to an official statement by the Prime Minister’s Office, in a telephone conversation with local council heads in southern Israel shortly after the war began). What happened later was, ostensibly, part of a well-planned strategic game plan. Netanyahu cleared, piece by piece, the geopolitical chessboard, with each victory and each achievement (Hamas-Hezbollah-Syria-Iran) portrayed as part of a sophisticated strategy aimed at total defeat of the enemy and the creation of a new regional reality.

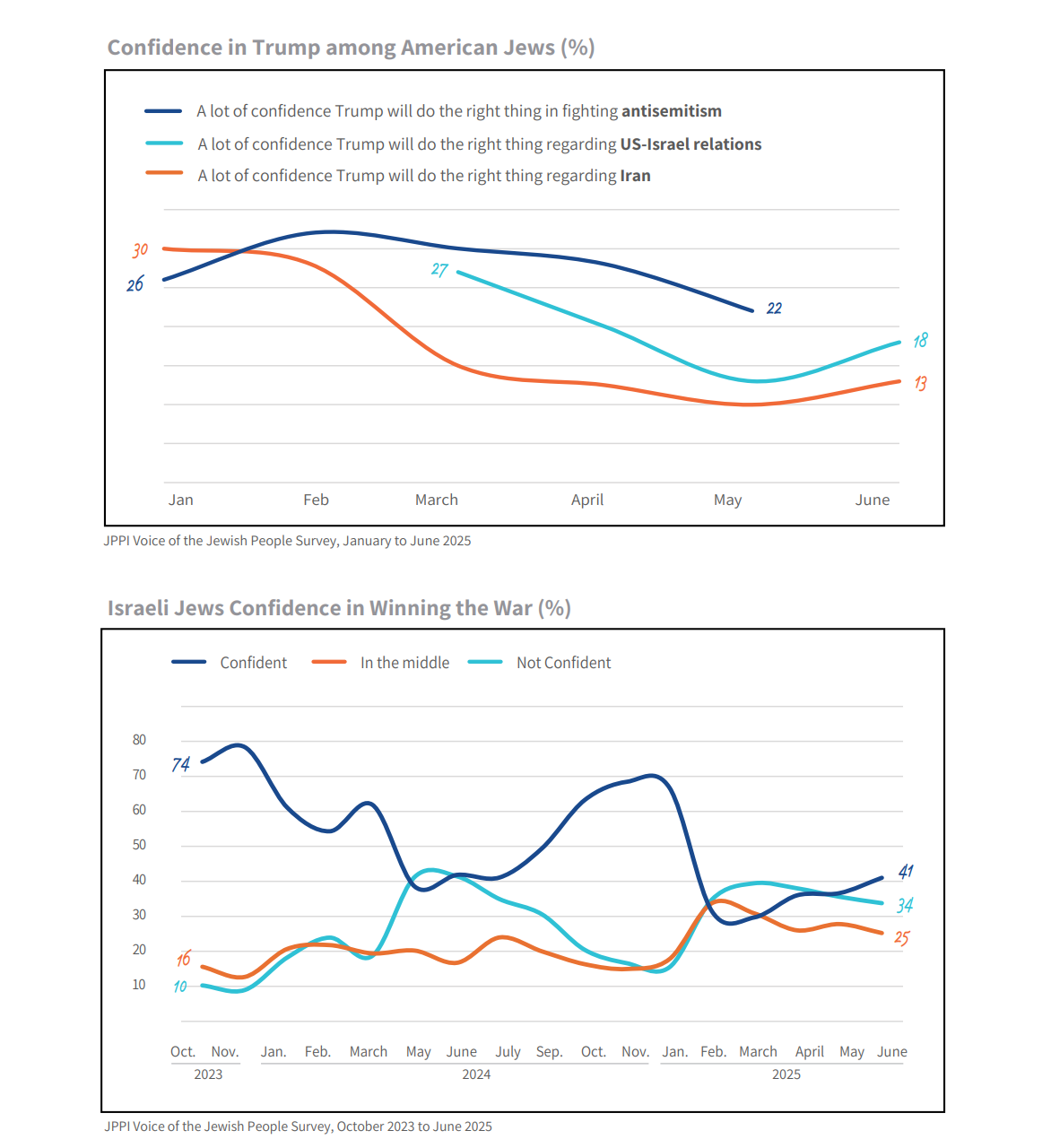

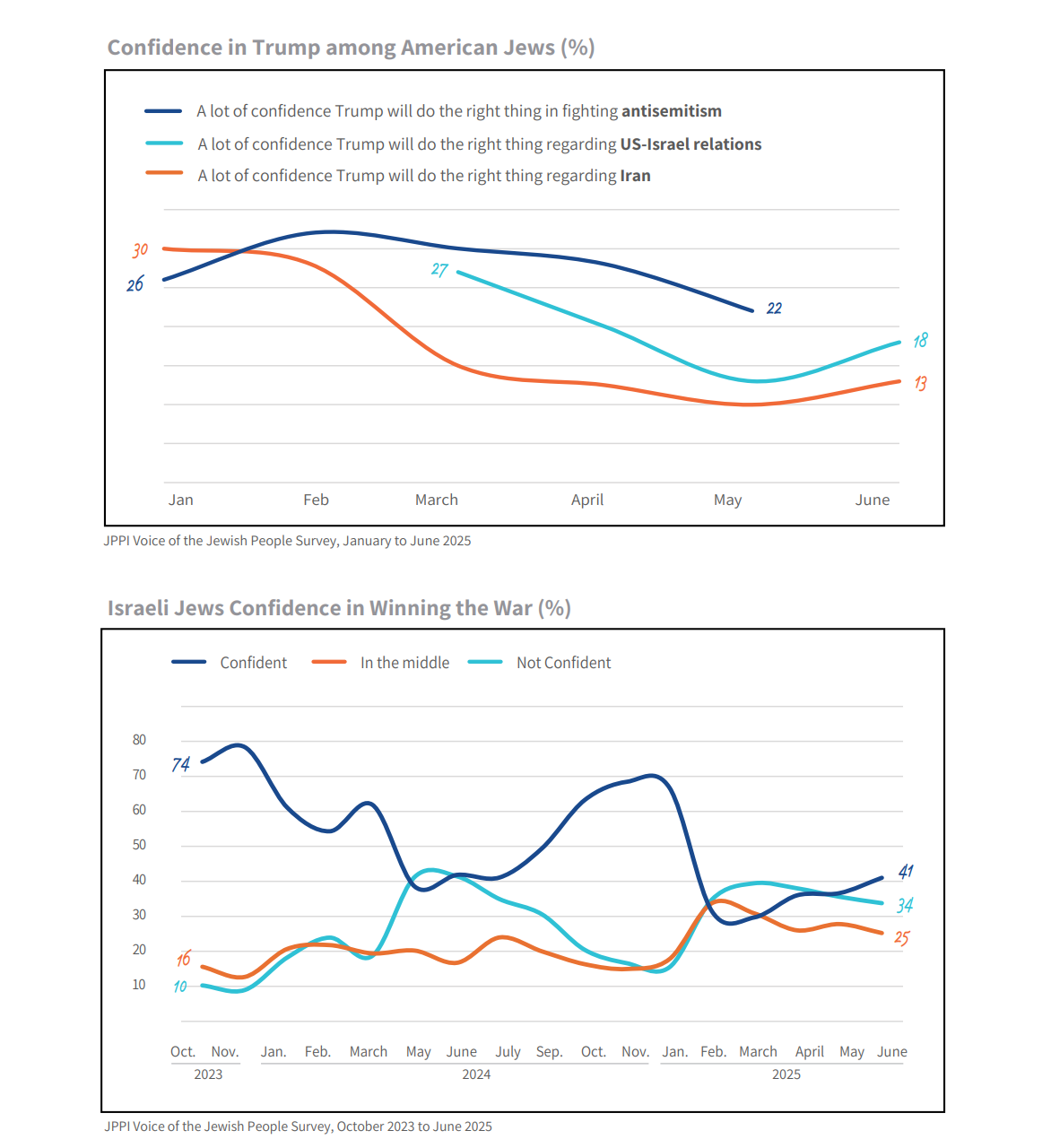

Politically, the government survived the second year after the disaster, contrary to many early forecasts, and despite Netanyahu’s significant unpopularity and the coalition’s weakness. A growing majority of polls have shown that the Israeli public disagrees with the government on three key issues: the return of all the hostages, ending the war, and establishing a state commission of inquiry.

At times, it has seemed that Netanyahu was taking a “the ends justify the means” approach, subordinating all war management decisions to one central goal – the continued survival of his government and the holding of the next Knesset elections as close as possible to their scheduled time, October 2026.

Within this framework, he acceded to the demand of the two far-right factions in the government, Religious Zionism and Otzma Yehudit, to resume fighting after the completion of Phase 1 of the hostage deal signed in January 2025. He also avoided, throughout the war, holding any substantial discussion on “the day after” in Gaza and the West Bank, fearing that such a discussion would spark a crisis with his far-right partners. Arab states have conditioned any future Gaza scenario on the Palestinian Authority (PA) taking a central role there.

By contrast, there was a major improvement this year, from the government’s perspective, regarding one international issue – Israel’s relations with the United States. Netanyahu and Trump have enjoyed a second honeymoon since the latter’s election for a second term, after four years out of office. The first 15 and a half months of the war were difficult for Netanyahu under the Biden administration. Biden expressed shock at the Hamas massacre, declared his public support for Israel, and was quick to send significant military aid. He warned Iran not to get involved (his famous mid-October “Don’t” speech). However, disagreements between him and Netanyahu deepened as the war dragged on. In May 2024, Netanyahu ignored Biden’s demand not to invade Rafah. The U.S. responded by imposing a de facto embargo on supplying the Israeli Air Force with heavy aerial munitions, as well as selling large Caterpillar (D9) bulldozers to the IDF, arguing that they cause disproportionate destruction of homes. Netanyahu did not hide the fact that he was waiting for his friend Trump’s return to power.

The War in Gaza

In July 2024, 12 children were killed by a Hezbollah rocket in the Druze town of Majdal Shams in the Golan Heights. Apparently aimed at the nearby Hermon outpost, the attack turned out to be a colossal mistake by the Shi’ite organization. The grave incident and subsequent public outrage resolved a months-long dispute between Netanyahu, Defense Minister Yoav Gallant, IDF Chief of Staff Herzi Halevi (both of whom were later dismissed by Netanyahu, mainly because they refused to support a draft law in the form he demanded), and other high-ranking IDF personnel. Since April/May, Gallant and the IDF had been trying to wrap up the Gaza campaign, to reach a comprehensive hostage deal, and to shift the military effort to Lebanon. Netanyahu had opposed these efforts and imposed his own will. In May, he also ordered the IDF to enter Rafah despite American objections.

The deadly rocket fire on the Golan instantly shifted the war priorities. The cabinet added victory over Hezbollah in Lebanon, and improving security along the northern border to the list of war objectives. Accordingly, the IDF gradually shifted the main weight of its operations to the northern front, as the primary arena, with Gaza once again becoming secondary (see below). This shift was reflected in the transfer of operational focus and, later, the redeployment of a large segment of the frontline brigades, both regular and reserves, from Gaza to the Lebanese border, and then into Lebanon itself.

Mainly reserve brigades remained in Gaza, with fewer troops and a narrowed scope of military activity. That activity focused on attempts to destroy Hamas weapons production and defensive infrastructure (tunnels and bunkers) throughout the Strip. After the fall of Rafah, Hamas ceased functioning as a “terrorist army” in battalion and brigade frameworks, and instead operated as a loose network of local guerrilla groups, with its senior leadership weakened in influence. The thousands of fighters killed (about 20,000, per IDF estimate) were soon replaced by youths aged 16-18 for the most part, with only basic training in weapons operation, who were sent to harass the Israeli forces through sniper attacks, close-range RPG fire, and IEDs. Some of these explosives were assembled from unexploded Israeli bombs dropped by the air force. These small-scale guerrilla actions regularly inflicted casualties on IDF units, often catching them static and exposed. The prolonged deployment of both regular and reserve troops – in what was already the longest campaign in IDF history – also led to a relatively high number of fatal operational accidents, causing numerous deaths and injuries.

Although Palestinian resistance in Rafah gradually collapsed, the IDF continued operations there, mainly in search of the leader of Hamas in Gaza, Yahya Sinwar, whom intelligence reasonably suspected to be hiding in the area. In October 2024, a force of trainee IDF squad commanders ultimately found him, by chance, in the Philadelphi Corridor near the Egyptian border in Rafah. Targeted assassinations also killed two other Hamas senior military leaders, Yahya Sinwar’s brother Mohammed Sinwar, and the veteran terrorist Mohammed Deif. But even before this, in late August, a tragic event had occurred in the same area. After a series of operations in which the IDF and Yamam (Israel’s National Counter-Terrorism Unit) had succeeded in freeing hostages from Hamas captivity, Hamas placed the remaining hostages under stricter guard, ordering their murder in any instance where a rescue operation was suspected. Six hostages, who had been forced to serve as “human shields” for Hamas leaders, were brutally murdered by their guards, shortly after detecting IDF movement above the tunnel where they were held.

The bodies of the six were discovered the next day by an IDF unit, sparking widespread public outrage. Across the country, large spontaneous public demonstrations broke out after months in which the hostage protest movement’s activity had diminished. Netanyahu now found himself in a bind: he opposed a deal under the terms demanded by Hamas, and sought to avoid ending the war for fear of his coalition collapsing. This was the background for the leak of classified documents involving aides from his office. The documents, based on intelligence obtained by Aman (the Military Intelligence Directorate) about Hamas activity, were leaked to the German newspaper Bild, attempting to show that it was Hamas that was deliberately stalling the agreement, drawing motivation from the pressure exerted by the hostage families via the protest command center advocating their release. The report was treated with distrust by the Israeli media, which exposed the involvement of the Prime Minister’s Office in the affair. Subsequently, a Shin Bet and police investigation led to the arrest of two Netanyahu aides; one has already been indicted.

This scandal overlapped with another affair that further entangled Netanyahu and his associates. It was revealed that at least three of his spokespersons had extensive business dealings with Qatar, some during the war itself. Although Qatar is not formally an enemy state, and is also a mediator in the hostage negotiations, the Doha regime is highly unpopular with the Israeli public in light of revelations about its extensive financial assistance to Hamas, which also used the money for terrorism. The investigation in this case is still underway, but it has deepened public skepticism about Netanyahu’s conduct and provoked harsh criticism of his circle of associates, who allegedly continued to receive money from Qatar at a time when Qatari funds were indirectly financing the killing of Israelis.

Nevertheless, Netanyahu continued to insist on avoiding a final hostage deal, despite various proposals put forward by the mediators – the U.S., Egypt, and Qatar. Circumstances changed only after Trump’s victory in early November. The incoming president maintained coordination with the outgoing administration on one major issue – the hostages. Trump frequently emphasized the urgent need to end the hostage saga and publicly expressed identification with their suffering. Trump even appointed his confidant, Steve Witkoff, as his special envoy on this issue (later asking Witkoff to also mediate on the Iranian nuclear issue, the Russia-Ukraine war, and other matters).

While Netanyahu repeatedly delayed the talks, he somehow managed to persuade the Biden administration to “absolve” him and attribute responsibility for the obstruction to Hamas, contrary to the professional opinion of most of the Israeli negotiating team and the intelligence officials. During those months, from September 2024 to January 2025, the fighting continued mainly in northern Gaza. The IDF conducted large-scale operations in Jabalia, Beit Hanoun, and Beit Lahia, leaving massive destruction in their wake. Most of the Palestinian civilian population fled.

Trump acted differently from Biden. Witkoff was sent to Doha to help the Biden team close a deal, and then forced Netanyahu to meet with him on Shabbat in Jerusalem, pressing Netanyahu to sign a deal on the eve of Trump’s inauguration. Over the next two months, Hamas returned 30 live hostages to Israel, including two who had been held for a decade, as well as eight bodies of fallen soldiers. In exchange, the Palestinians received hundreds of security prisoners held by Israel, including dozens serving life sentences. The IDF, per the agreement, withdrew from some areas it had occupied in Gaza.

On March 18, Netanyahu decided to resume the war and break the ceasefire, citing Hamas violations regarding the pace and manner of implementing the agreement. The Israeli assault began with massive air strikes that killed nearly 400 Palestinians, most of them civilians. Among the dead were high-ranking officials in Hamas’s political bureau. The operation, which later evolved into a campaign named “Gideon’s Chariots,” exerted heavy military pressure on Hamas, and led to Israel’s occupation of more than 70% of Gaza’s territory. The Palestinian population was pushed into three enclaves, in Gaza City, refugee camps in central Gaza, and the Al Mawasi area on the southern coast.

In May 2025, Israel took another step: it halted the transfer of humanitarian aid to Gaza via the UN and various international agencies, placing oversight instead into the hands of an Israeli-American foundation. The official rationale was that under the previous system Hamas had seized some of the supplies and resold them for profit.

The decision proved catastrophic. Between mid-March and late July, 50 IDF soldiers were killed in Gaza and hundreds were wounded. The number of Palestinian fatalities rose to over 60,000, according to Hamas figures. The IDF inflicted immense damage across the Strip. Perhaps worse – by late July, a severe humanitarian crisis had unfolded, with growing international allegations that Israel was deliberately starving the population. The aid foundation proved unable to manage the vast project. Aid entering Gaza did not match the needs, and chaos at distribution centers prevented many civilians from receiving food. In addition, there were repeated incidents in which IDF soldiers shot and killed civilians who had come to collect supplies. By the end of July, under mounting international pressure, Netanyahu was forced to reverse course. Israel allowed the UN to resume food provision, opened corridors for aid trucks, declared humanitarian pauses for aid distribution, and even air-dropped food itself for the first time.

The international diplomatic fallout was not long in coming. France was the first to announce its intention to recognize a Palestinian state, and soon after other countries joined, including Britain, Canada, Australia, and others. The combination of Hamas’s starvation campaign and Israel’s ongoing fighting in Gaza without any political horizon caused enormous damage to Israel’s international standing.

In early August, Israel once again faced the same dilemma that had repeatedly preoccupied Jerusalem throughout the war: Should it move forward with a hostage deal, despite the political risks to Netanyahu and the fear that without a total defeat of Hamas, some danger would remain for Israel’s southern border communities? Or should it continue trying to decisively defeat Hamas, at the cost of potentially losing any chance of rescuing hostages alive, more IDF casualties, re-establishing full military rule across the Strip – and the grave international isolation such a course could bring?

The most pressing challenge remains the question of “the day after.” With some 70 percent of the Gaza Strip destroyed, there is deep uncertainty about its ability to be rehabilitated, requiring reconstruction on a massive scale. Throughout the war, Israel has refrained from presenting or clarifying any “day after” political plans, most of which had been formulated in various Arab capitals and Washington.

Trump at one point dramatically unveiled his “Gaza Riviera” plan, but it never advanced beyond declarations – despite enthusiastic reception among extreme elements in the Israeli coalition.

In Israel, three main scenarios for the “day after” have been discussed:

Continued military rule by the IDF – not only in terms of security but also civilian administration. Such a situation would allow for tight civilian supervision over everything related to reconstruction and prevent Hamas from being able to rebuild itself.

Investment in local militias in Gaza that could counter Hamas. One such group, Abu Shabab, is presented as a potential force to confront Hamas and block its return to power. Israel has worked with this faction, which operates mainly in Rafah, and reportedly has provided it with equipment and arms. Yet this is seen as a short-sighted plan that is unlikely to anchor long-term stability in the bloodied Gaza Strip.

Establishing a new governing body in Gaza, led by technocrats and Palestinian Authority (PA) officials, while preserving IDF operational freedom – similar to the current situation in the West Bank, where Israel does not handle civilian administration in Areas A and B, but conducts military operations as it sees fit. The problem with this plan, supported by Israel’s Arab partners, is that Netanyahu’s coalition partners have rejected it outright, refusing to allow any PA foothold in Gaza’s future.

The War in Lebanon

Israel responded to the Hezbollah killing of Druze children in the Golan with two dramatic moves: the assassination in Beirut of Fuad Shukr (known as Haj Mohsen), Nasrallah’s chief military adviser, and on the same night, the assassination of Ismail Haniyeh, head of Hamas’ political bureau, while he was staying at a government guesthouse in Tehran.

From there, the war evolved into a patient peeling away of Hezbollah’s defensive and offensive capabilities. Israel gradually escalated its operations but did so cautiously and without unnecessary boasting. Secretary-General Nasrallah, who Iran and its radical axis partners considered to be the leading expert on Israeli policy and society, completely misread the situation this time. Although some of his aides warned him to act more forcefully and launch heavy missile barrages at the Tel Aviv area, Nasrallah chose to “communicate” with Israel through limited, measured strikes – a policy Military Intelligence dubbed the “beacon method.”

In this case, Hezbollah behaved exactly as its Israeli adversaries had hoped. The measured exchanges allowed the Israeli Air Force to gradually escalate its strikes, knocking out more and more of Hezbollah’s systems. A series of blows delivered throughout September 2024 brought the organization to decisive defeat, at least this time around.

In mid-September, Mossad and the IDF launched “Operation Beepers” – a coordinated detonation of thousands of pagers held by Hezbollah operatives, after the organization had acquired them in a sophisticated Mossad sting operation. Dozens of operatives were killed and thousands were injured, but the main impact was psychological: Hezbollah was caught utterly unprepared. International media marveled at the sophistication and lethality of the Israeli operation, a sort of reversal of the reactions to the massacre on October 7 a year earlier.

Nasrallah himself sank into deep depression, withdrew into his bunkers, and avoided taking initiative. He clung to his measured-response doctrine, as Israel tightened the noose around him and killed many other senior figures, including Ali Karaki, Ibrahim Aqil, and the entire top echelon of the organization’s Radwan commando force. Nasrallah died still clutching his measured strategy. Israeli bombs hit the underground bunker where he was hiding in Dahiyeh, in Beirut’s Shiite quarter, in late September. Hezbollah failed to mount a significant retaliatory strike on Tel Aviv. Days later, large IDF ground forces invaded southern Lebanon. Hezbollah struggled to fight back. By this point, 60-70% of the organization’s firepower had already been destroyed – medium-range missiles, short-range rockets, drones, and air defense systems – and the new leadership, headed by Nasrallah’s drab deputy, Sheikh Naim Qassem, proved unable to rally the organization. Only about 10% of Hezbollah’s reservists reported for duty; most, sensing impending military failure, stayed home.

By the end of October, the IDF had cleared most of southern Lebanon, south of the Litani River. Hezbollah fighters abandoned the area, as did most of the civilian population. Israeli ground forces uncovered and destroyed bunkers, tunnels, weapons depots and production facilities. Overall, on the Lebanese front of the post-October 7 war, 84 IDF soldiers and 46 Israeli civilians were killed, as were more than 5,150 Lebanese, about 4,000 of whom were Hezbollah operatives, according to IDF estimates. Another 9,000 were wounded. Israeli intelligence assessed that more than a third of Hezbollah’s standing force was rendered inoperative (killed or severely injured). The damage to Hezbollah capabilities closely matched prewar Israeli estimates.

During the war, about 1.6 million Lebanese civilians – mostly Shiites – were displaced from their homes in the south, the Bekaa Valley, and Beirut. The Dahieh suburb in the south of Beirut was completely emptied, with about 300 buildings destroyed by Israeli bombings. Afterward, many residents returned to their homes north of the Litani River, but the belt of villages within 5 kilometers of the Israeli border remained largely destroyed and deserted. For comparison, by late July, 74% of Israeli residents evacuated from communities within 3.5 kilometers of the northern border had returned home. According to Israeli intelligence, morale in Hezbollah’s ranks remains low, the commitment of reservists weak, and Qassem is still struggling to step into the shoes of Nasrallah, who ruled Hezbollah with an iron fist for 32 years.

A ceasefire was achieved under American mediation at the end of November last year. Hezbollah retained hundreds of rockets capable of reaching central Israel and several thousand covering the north, but its firepower, command, and control systems remained crippled. Israel had accused Hezbollah of thousands of ceasefire violations, launched about 500 aerial strikes into Lebanon since the agreement, and killed about 230 Hezbollah operatives by the end of July 2025. But, in this entire period, Hezbollah fired only once into Israeli territory, at Mount Dov, two days after the ceasefire, which appeared to be a token gesture before full compliance.

Israel’s continued strikes, with full American backing, reflect the new balance of power. Israel, seeking to capitalize on its victory and establish a deterrence equation in which it alone attacks in response to Hezbollah activity south of the Litani River, without Hezbollah daring to retaliate. For now, the formula is working. The success lies not only from the decisive results achieved by the IDF and the Mossad, but also in the agreement forged afterward. The ceasefire agreement almost completely removes the UN’s UNIFIL force from the equation while granting the United States an unusual role: an American general and his team were stationed in Beirut to help enforce the agreement.

This U.S. backing emboldened Lebanon’s new president and chief of staff to take a tougher stance against Hezbollah. Unlike after UN Security Council Resolution 1701 ended the Second Lebanon War in 2006, this time the agreement is being strictly enforced by the authorities in Beirut, with American support. The Lebanese government, coordinating behind the scenes with Israel, is aiming to limit Hezbollah’s role, even pushing toward its complete disarmament. At the same time, Lebanese security forces are fighting to stop weapon smuggling from Syria and Iranian attempts to resupply Hezbollah through the Beirut airport. Several Iranian aircraft have been turned back after suspicions of smuggling arose. The general attitude toward Hezbollah, especially among Lebanon’s non-Shiite communities, has become more hostile, and there is growing support for disarming the organization – the last militia left to do so under the Taif Agreement that ended Lebanon’s civil war in 1989.

As for Israel, it currently maintains five manned military outposts inside southern Lebanon, at strategic points near the border. Hezbollah has so far refrained from approaching these contact lines. Senior IDF officers believe the current operational model serves Israel’s interests and restrains Hezbollah’s activity. Further, some explicitly argue that the model could be applied to Gaza: if it works against Hezbollah, a far stronger organization than Hamas, it could work against Hamas too.

Syria

The fall of the Assad regime in Syria was one of the most significant regional events this year, alongside Israel’s wars on various fronts. In this case, Israel’s role was indirect, but one could argue that IDF operations acted as a kind of detonator that triggered the chain of events.

According to senior Turkish intelligence officials in contact with Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (the umbrella organization of Sunni rebels), the rebels had long been waiting for a ceasefire between Israel and Lebanon. Once the ceasefire was reached, they analyzed its terms and concluded that Hezbollah’s willingness to accept such harsh conditions reflected its dire state and inability to fight. And thus, they assumed that Hezbollah would be unable to send forces to defend the Assad regime if they acted against it.

The rebel advance, which began in Idlib, faced almost no resistance. Within 11 days, the whole of Syria had been conquered, except for small Alawite enclaves in the northwest (which were later taken as well). The Syrian army collapsed, and President Bashar al-Assad fled to Moscow, where he received Russian protection. What was not achieved in almost 13 years of civil war was decided in less than two weeks. The rebels also quickly took control of southern Syria, adjacent to the Israeli border.

The IDF operated vigorously during this period. Initially, it targeted – mainly from the air – military camps and heavy weapons depots, to prevent them from falling into the hands of the new regime. The IDF destroyed dozens of aircraft, helicopters, and drones, as well as missile stockpiles and numerous air defense batteries (which would serve it well later in its breakthrough attack on Iran).

In addition, the army seized, without resistance, a buffer zone in Syrian territory in the Golan and Hermon, 7 to 15 kilometers from the border. Israel continues to hold nine outposts in Syria, the largest and most remote of which is the Syrian Hermon outpost. The new Syrian regime, led by former jihadist Ahmed al-Sharaa (also known by his nom de guerre, Abu Mohammad al-Julani), has publicly protested this several times, but has avoided direct military confrontation with Israeli forces. By contrast, Netanyahu and Defense Minister Yisrael Katz have repeatedly threatened Syria and, in several cases, ordered punitive strikes, for various reasons, against the new regime’s military camps and convoys.

In mid-July, tensions escalated sharply following a massacre carried out by regime-backed Sunni Bedouin militias against Druze residents of the town of Sweida, about 80 kilometers east of the border with Israel. Some 1,400 people were killed, and many Druze women were abducted and raped. Israel bombed regime and militia convoys, and its intervention brought the fighting to a halt, but Druze expectations for Israeli protection remain high. As in Lebanon, Israel is taking steps to enforce the new balance of power with an aggressive, uncompromising approach – very different from its past behavior. It almost welcomed every opportunity to respond to violations militarily, unconcerned about potential complications, due both to its military advantage and the lessons of October 7.

Relations with the new regime remain complicated. The Trump administration hoped to bring Syria into the Abraham Accords and present this as a diplomatic achievement, but al-Sharaa struggled to deliver, given Israel’s continued presence in Syrian territory, not to mention Israel’s control of the Golan Heights since 1967. For its part, Israel is deeply suspicious of the new regime’s ties to Sunni fundamentalism and continues to regard the new president as a “jihadist in a suit.”

Yet, for Israel, the most significant development in Syria was the blow to the radical Shiite axis led by Iran. Not only have Iran, Hezbollah, and Hamas been battered militarily over the past year, but the most critical piece of the “Shiite Crescent” – the geographic corridor through which Iran had projected power across Iraq and Syria into Lebanon – lost its central piece: Syria itself. This effectively cut off the smuggling route Iran had used for years to arm Hezbollah, greatly reducing the threat against Israel.

Iran

The most dramatic strategic development of the year occurred in Iran. What is astonishing is that within weeks, the international community seemed to have all but forgotten about it; once the fighting stopped, global media attention shifted away. For nearly 20 years, Israel had prepared for – and Netanyahu had often spoken of – the possibility of striking Iran’s nuclear facilities. Many doubted it would ever happen, with some dismissing Netanyahu as either arrogant or gutless. But the prime minister saw in the course of the Gaza war an opportunity to realize his long-held vision, recognizing that Trump’s return to office opened doors no previous U.S. president – not Biden, not Obama, not Clinton – had been willing to open. (There was no overlap between the terms of office of Netanyahu and George W. Bush).

Israel and Iran had already exchanged blows twice in 2024, as the Israel– Hezbollah–Hamas conflict escalated. In April of that year, Iran launched hundreds of ballistic missiles, drones, and cruise missiles at Israel. Most were intercepted by the U.S.-led regional defense initiative, with the participation of American, British, Jordanian, and Gulf forces. Israel retaliated by striking a strategic radar site in Iran’s air defense system. Another round followed in October when Iran again launched hundreds of projectiles, causing somewhat more damage but no fatalities. Israel’s counterstrikes again hit Iran’s radar and air defense systems.

These earlier strikes paved the way for what followed. Like the gradual dismantling of Hezbollah’s systems, Iran’s air defenses were peeled away in preparation for the decisive assault. Behind the scenes, Israel had been preparing for months. In January 2025, with Trump’s return to the White House, Netanyahu ordered the defense establishment to accelerate preparations for a direct Israeli attack on Iran’s nuclear sites. The plans were upgraded and refined, with the conclusion that a large-scale campaign led by the Air Force would be more effective than a Mossad-directed sabotage and assassination strategy. The Mossad capabilities were incorporated, but it was clear that the IDF would take the lead.

On June 9, in a secure transatlantic call, Netanyahu finally obtained Trump’s approval. The U.S. president gave Israel the green light. The IDF chief of staff, Eyal Zamir, had already assured the cabinet that the plan was ready and likely to succeed – but emphasized that implementation depended on American consent. With Trump’s agreement, the operation was launched just before midnight on June 12–13.

It quickly became clear that this was not a one-off raid, but a sustained campaign. As Air Force Commander Maj. Gen. Tomer Bar had told planners months earlier –pilots needed to operate in Iran “as if it were the first circle, not the third,” meaning to attack freely and repeatedly despite the 1,000-plus kilometer range.

The operation succeeded beyond expectations. Its key achievement, according to planners, was the attainment of air superiority. The Air Force simply “carved out,” as Zamir put it, a threat-free corridor through the skies over Syria, Iraq, and Iran. All potentially dangerous air defense batteries were destroyed, enabling hours of largely unimpeded operations over Iran. Instead of “stand-off” strikes from a distance or the airspace of a neighboring country, Israeli jets and drones operated in “stand-in” mode for an extended period, even over Tehran itself. This was made possible by decades of painstaking intelligence-gathering operations. Israel knew exactly where Iran’s critical weak points lay – and struck them.

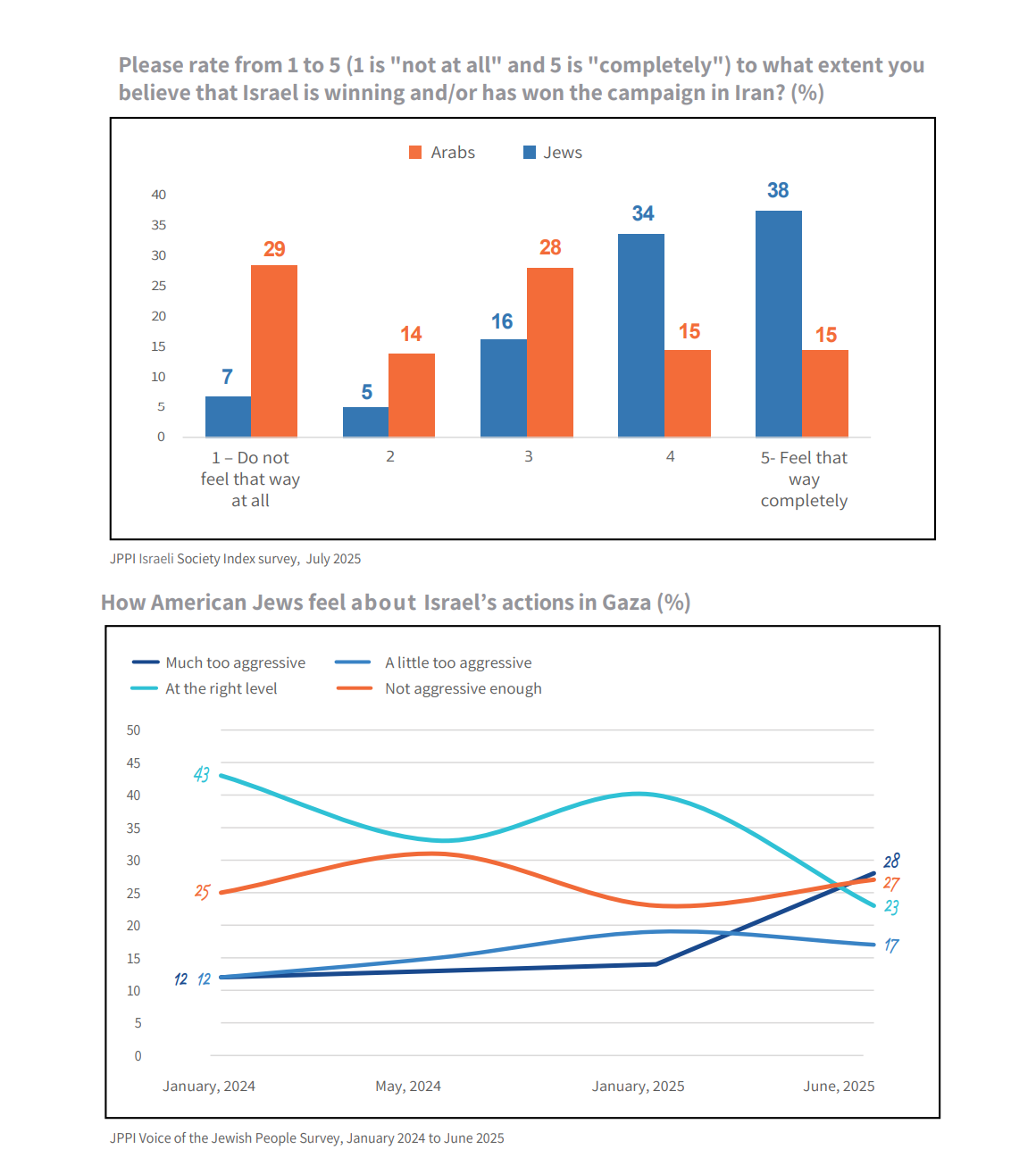

Over 12 days of fighting, Israel hit Iran’s key nuclear sites at Natanz and Isfahan, destroyed air defense systems, missile stockpiles and launchers, and killed most of the country’s military and security leadership (except the supreme leader and the president) along with dozens of top nuclear scientists.

On June 22, Trump escalated further, ordering the deployment of B-2 strategic bombers that dropped 13-ton “bunker busters” on the underground Fordow facility. Israel had long acknowledged that it could not penetrate the site’s depths, 80-90 meters underground, with its own munitions. The alternative would have been a risky ground attack that could have been lengthy, complicated, and extremely costly. Trump, seizing on Israel’s success, opted for U.S. involvement. The bombers caused heavy damage to the Fordow site (according to Trump’s claim, an exaggeration, it was “completely obliterated” and, with it, the entire nuclear program). A day later, a ceasefire was reached and the 12-day war ended, giving Israel a clear advantage on this front as well, although not a decisive victory.

Trump also reasserted the geopolitical chain of command in ordering Netanyahu to recall Israeli aircraft already en route to Iran for further strikes hours after the ceasefire was announced and after the Iranians had already violated it with a missile launch of their own. But Israel had achieved two of Netanyahu’s most ambitious goals – a powerful strike on Iran’s nuclear program with U.S. backing, and later even active American participation.

After the campaign, a debate soon erupted over whether such a campaign had been truly necessary. Was the sword really at Israel’s throat, as the former Mossad chief, the late Meir Dagan, put it a decade ago when debating such an attack? Netanyahu, Zamir, and Mossad chief David Barnea argued that it was unavoidable: Iran had amassed a stockpile of highly (60%) enriched uranium, resumed their work on weaponization (adapting ballistic missiles to accommodate nuclear warheads), and planned to produce about 8,000 ballistic missiles by 2028. In their view, there was an urgent need to act. But in truth, this also fits into the rare window of opportunity Netanyahu created, thanks to Trump, during the war. Out of the chaos, an opportunity emerged, and political and military leadership could not pass it up, despite the quagmire in Gaza and the debate over how to end the war there.

During the campaign, Iran launched more than 500 ballistic missiles and about 1,000 drones at Israel. All the drones were intercepted, except one that hit a house in Beit She’an but caused no casualties. Roughly 10% of the missiles were not intercepted and landed in Tel Aviv, Petah Tikva, Holon, Bat Yam, Haifa, Beersheva, and in the vicinity of various Air Force bases. Key facilities – including the Weizmann Institute, Bazan oil refinery in Haifa, and a defense facility in the Galilee – suffered heavy damage. Thirty people were killed in Israel, and more than 3,000 were hospitalized with injuries. The damage wreaked on hundreds of buildings was worse than Israel had ever experienced. Still, the effort on the home front was seen as a huge success – with the number of casualties less than 10% of the lowest early projection the IDF presented to the cabinet. The public’s overwhelming compliance with Home Front Command instructions, along with the long warning time (10–12 minutes), saved many civilian lives. Like Hezbollah before it, Iran struggled to launch large, coordinated barrages after its command and control capacities were disrupted. And the fact that Hezbollah, still reeling from its own defeat, refrained from joining the Iranian attack, contrary to Tehran’s long-held strategy, eased the pressure on the Israeli home front.

Experts remain divided over the extent of the damage inflicted on Iran’s nuclear sites, and the degree to which Tehran’s program was set back. There is a plausible scenario that the surviving Iranian leaders might now accelerate efforts to produce a nuclear weapon, by any means necessary and despite Trump’s threats, believing it the only insurance policy for the threatened regime. Neither Israel nor the U.S. really sought to overthrow the regime during the short campaign, although some experts supported it. There is also concern that the divided Iranian public will rally more closely around the regime, given the heightened external threat.

In July, Trump threatened to resume strikes if Iran did not respond to his pressure to abandon its nuclear program and sign a new agreement. The president ignored another remaining problem: the mystery surrounding the whereabouts of more than 400 kilograms of highly enriched uranium – enough, after further enrichment, to produce around ten nuclear bombs. It appears that the regime managed to hide the uranium before the attack.

In any event, Israel’s impressive military and intelligence achievements boosted its regional status. Many Sunni states, long fearful of Iran, welcomed the blow it suffered. They also admired the extraordinary capabilities of Israel’s defense system, and its ability to obtain American support. Less impressed were the Houthi rebels in Yemen. They have continued to launch missiles and drones at Israel about twice a week since the summer of 2024, both in solidarity with Gaza and in coordination with Iran. Even so, it seems that the Houthi threat no longer preoccupies the Israeli public – many have stopped heeding the sirens, after having endured the far greater danger of Iran’s ballistic missile strikes.

Summary

This has been a dramatic, turbulent, and deeply unsettling year for Israel’s security and international standing. Only the shock of the horrific October 7 massacre, now approaching its two-year anniversary, left a deeper mark. The heavy shadow of that day continues to loom over Israel’s strategic reality, and it seems the country has yet to truly recover.

The government’s inability – and especially its unwillingness – to chart a way out of the ongoing war in Gaza, the never-ending hostage saga, the heavy toll of fallen IDF soldiers, and the physical and emotional exhaustion of the small group of civilians bearing the burden – all of these have led to a severe erosion of public morale and an unbearable sense of paralysis. The Israeli public, only beginning to process the trauma of the massacre, finds itself mired in a prolonged campaign with no endgame in sight.

In the international arena, Israel’s situation has worsened. Although it initially aroused empathy and a fragile legitimacy as the victim of a terror attack, this evaporated quickly as the war dragged on and the destruction in Gaza mounted. The high Palestinian death toll – even if many were Hamas combatants – led to accusations of deliberate ethnic cleansing, based on the leveling of tens of thousands of homes and enormous civilian casualties, without the IDF providing satisfactory explanations. The situation was exacerbated by the racist and inflammatory rhetoric of ministers and Knesset members, who openly called for Gaza’s erasure.

Added to this were problematic strategies – which emerged both from the right-wing parties in the coalition and some former senior officers – proposing siege, starvation, and even expulsion of the civilian population. The most extreme government factions did not hide their desire to bring about “voluntary emigration” of Gaza’s residents, even at the cost of a direct confrontation with Egypt in Sinai. These notions were dressed in softer language – economic development (“Gaza Riviera”) and international aid programs, but the international community did not buy it.

The peak of Israel’s political isolation came in July. The Israeli move to establish an independent body to distribute humanitarian aid in Gaza – as an alternative to the UN – collapsed. At the same time, mounting reports and images of hunger in Gaza spurred a fresh wave of condemnations and punitive measures against Israel. Twenty-eight Western countries – including France, Canada, Australia, and Italy – issued a rare joint statement demanding an immediate end to the fighting. They charged that Israel’s aid distribution model was “dangerous,” “fueling instability,” and undermining the human dignity of Gazans.

If the momentum toward recognizing a Palestinian state continues without an agreement with Israel, little may change on the ground – but Israeli diplomacy will suffer a serious blow. Countries that recognize Palestine will have to reassess their agreements with Israel to avoid violating their commitments to a Palestinian state. This could involve Palestine’s territorial integrity, as well as political, economic, cultural, and civil relations – and even lead to the cessation of trade with Israel.

The question of state recognition could also affect during discussions on the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court (ICC), whose chief prosecutor has already issued arrest warrants against the prime minister and former defense minister. Germany and Britain, for example, have refused to acknowledge the ICC’s jurisdiction in the territories and Gaza, partly because they did not recognize Palestine as a state. Wider recognition in Europe could change this stance.

Despite their recognition of a Palestinian state, it is important to note that Britain and France played a role in defending Israel from Iranian attacks last year. This situation is complex: Israel is becoming diplomatically distanced from its historical allies, and the prime minister is increasingly treated as a persona non grata.

The bottom line is that even if Israeli ministers stop visiting European capitals, Israel is becoming increasingly marginalized and could become an isolated, pariah state in the international arena. We are not there yet, but the slope has never been more slippery.

Above all this, the fundamental strategic problem looms: the lack of a clear political goal. The Israeli government claims that its war objectives are the return of the hostages and the destruction of Hamas – but it does not present a plan for the reconstruction of Gaza, does not talk about who will govern it the day after, and does not try to formulate a practical vision that will soften the growing international opposition. Into this vacuum enters the incitement of the extreme right – calls for starvation, deportation, indiscriminate bombing – which intensifies the gap between unbridled military power and increasingly eroding political legitimacy.

And here, against the backdrop of all this, America remains Israel’s only support. But under the new Trump administration this, too, may well become unstable. His regional policy is unpredictable, and his emotional zigzags create uncertainty instead of stability. The successes of Israel’s security establishment – mainly in other areas, such as eliminating senior Hezbollah commanders or preventing Iranian entrenchment – fail to change the overall image: Israel may be stronger militarily, but it is weaker diplomatically.

And at the same time, antisemitism is on the rise in the Western world. Jews and Israelis have been subjected to harassment and sometimes even physical attacks – mainly in Europe and North America – for supporting Israel or simply for being Jews. This wave of hatred erupted immediately after October 7, and although it erupted in response to the massacre, it quickly took root among those who believe that Israel is committing genocide.

In short, there is a troubling dissonance between Israel’s impressive upgrade in security capabilities and determined actions in the face of external threats, and its deteriorating international status and the deepening distrust among its closest allies. The fact that the government continues to promote ideas of annexation, expulsion, and damage to the democratic fabric within the Green Line only adds fuel to the fire.

There is no doubt that Israel now faces a historic opportunity to reshape the Middle East: Iran has been weakened, Assad is gone, and Lebanon has a pro-Western government with which it may be possible to reach a normalization agreement. But to seize the opportunity, Israel must choose between continuing a grueling, never-ending war or embracing a comprehensive strategic initiative to establish a new regional order. At this moment, Israel may be stronger and more secure militarily, but it is also isolated, divided, and lacking the clear vision needed to bring the longest war in its history to an end.