Generally, the October 7 Hamas onslaught and the resulting war, including the Hezbollah and Iran fronts, have strengthened ties between Diaspora communities and Israel. This applies to the mainstream Diaspora groups, especially those that constitute the organized Jewish community (federations, synagogues and religious denominational movements), national advocacy organizations such as the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) and the American Jewish Committee (AJC), as well as to important Israeli groups who have increased their identification with the Diaspora. Yet this effect has not been unidirectional. It has also increased the distancing from and criticism of Israel among certain Diaspora groups who are disconnected from Israel and/or Zionism. It also seems to have slightly decreased identification among certain Israeli groups who had previously strongly identified with the Diaspora. Further, it has surfaced tensions between the parts of the ruling government in Israel who represent a nationalist majority position, and leading Diaspora Jewish organizations, including those who are traditionally very pro-Israel and pro-Zionist.

The October 7 attacks and the war that followed can thus be better described as having had a general galvanizing and dynamic effect on the diaspora’s relationship with Israel. For the most part, they intensified the previously existing relationship of attachment or estrangement, respectively, and in a few cases, slightly changed the direction of the relationship or exposed inherent tensions within it. In no case was the relationship between the Diaspora and Israel unaffected.

Relationship of Diaspora Jews to Israel

1. The organized Jewish community and communally engaged Diaspora Jews

This mainstream segment of the Jewish community considers the Jewish people to be a “Community of Fate” with a shared Jewish destiny that unites Diaspora and Israeli Jews everywhere. Officially, of course, Jewish identity in the Western democracies consists of a privatized religious identity. In practice, it contains a strong ethno-national component, which expresses itself in transnational Jewish solidarity (We are One!) and promotes Jewish economic, political, social, and cultural flourishing. This orientation has the earmarks of a Jewish civil religion, and like all civil religions, has a sacred aspect to it. Thus, it has been described as consisting of “sacred ethnicity” and promoting “sacred survival.”¹

While some observers have commented that this orientation has thinned out over the years, it received a new lease on life after October 7. As the Hamas butchery became known, Diaspora communities extended massive support to Israel. Diaspora communities around the world raised $1.4 billion for Israel right after October 7. Half of this was raised by the Jewish Federations of North America (JFNA). In addition, federations and organizations in North America raised funding separate from the JFNA drive. UJA-Federation of New York raised $73 million, and the Chicago and Toronto Federations raised a combined $50 million. Another $91 million was raised by crowdfunding (reported on by AMI in coordination with the Ministry of Diaspora Affairs and Combating Antisemitism).²

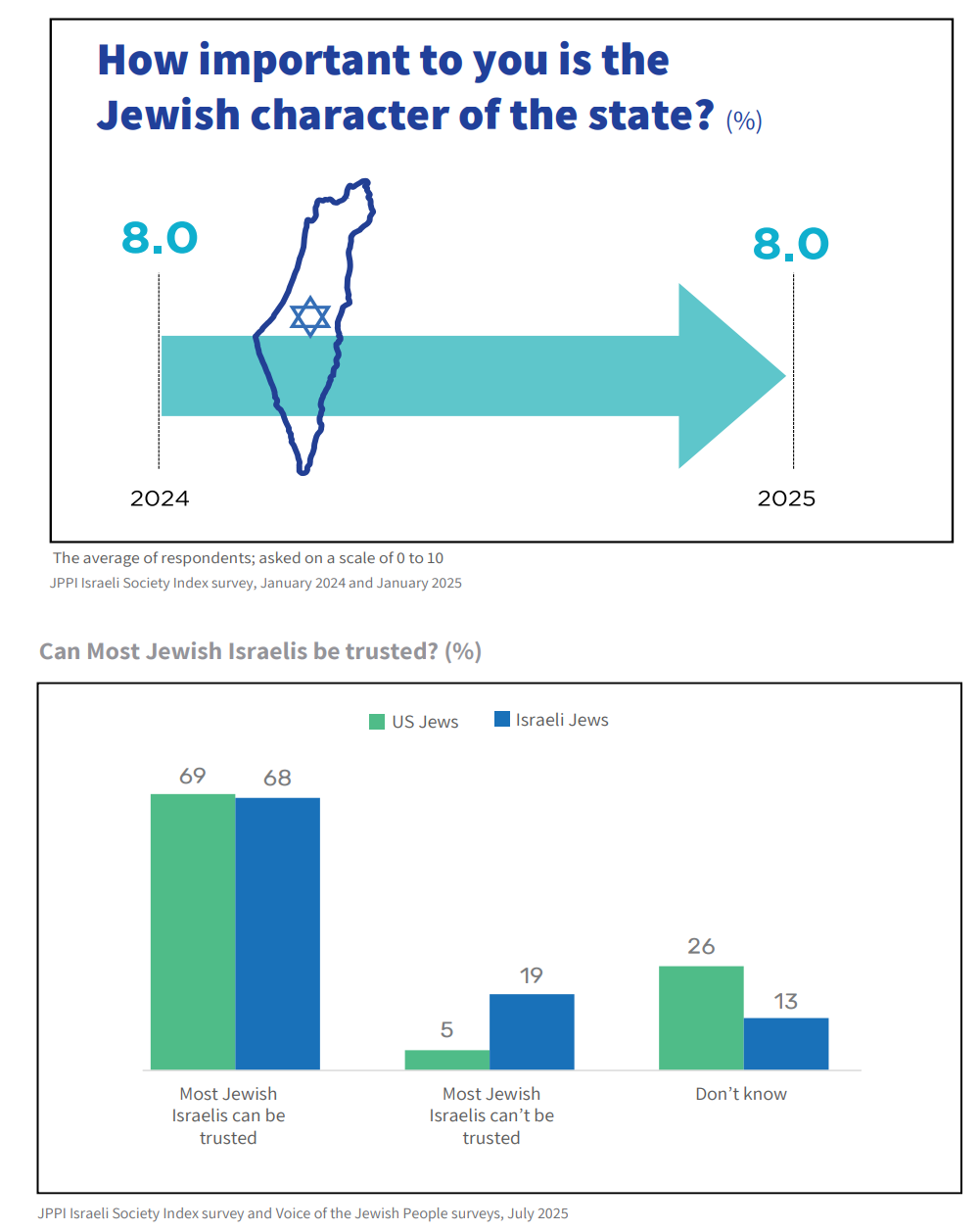

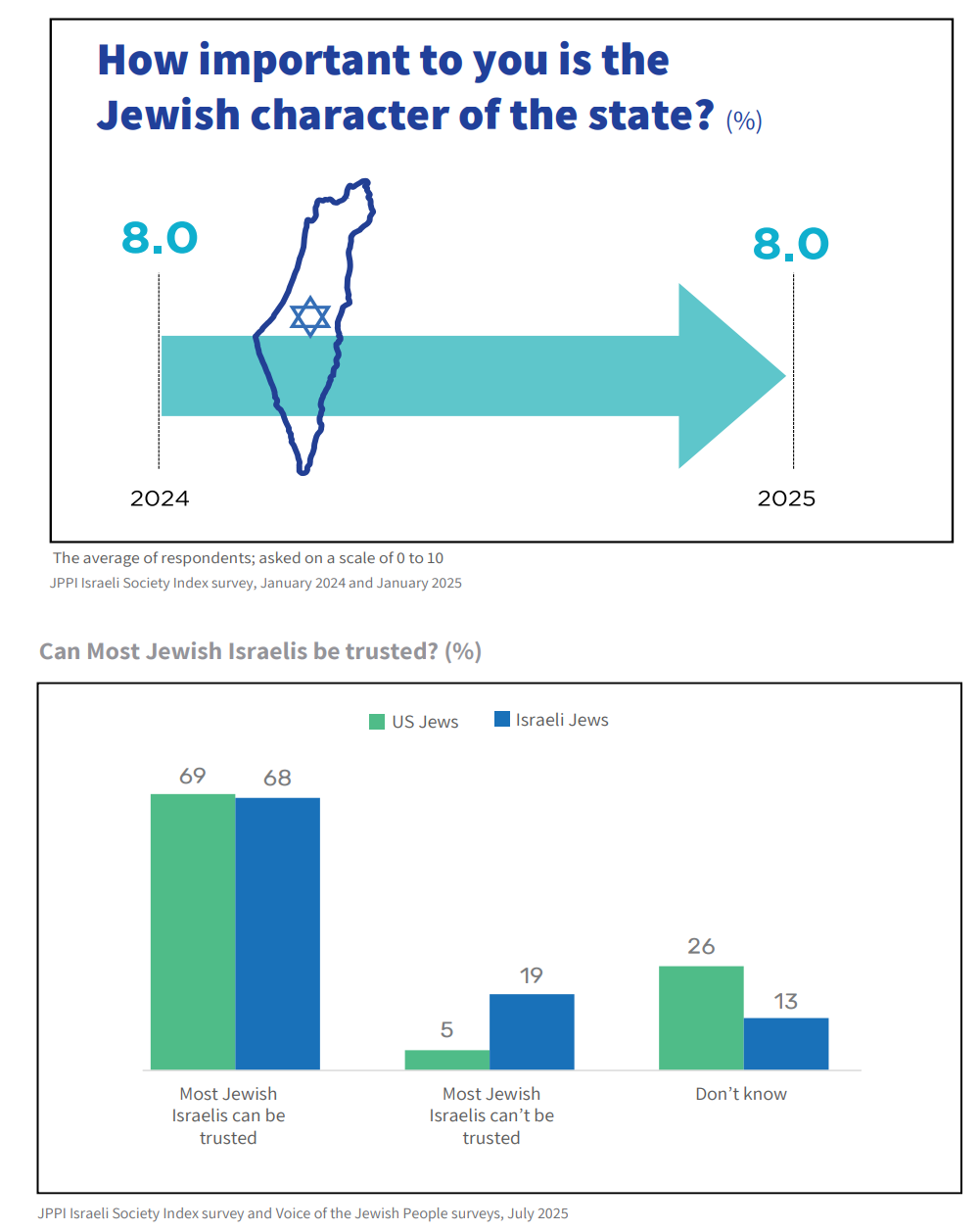

Additionally, some 58,000 volunteers came to Israel to support the towns and kibbutzim in the Gaza envelope that had been attacked, and the evacuees. Many Diaspora Jews took part in pro-Israel demonstrations, events, and gatherings of various sorts.

The effects of the October 7 attacks were also reflected in survey data. According to a spring 2024 American Jewish Committee (AJC) survey, 45% of American Jews said the events of October 7 had strengthened their connection to Israel; (21% said the events had very much strengthened their connection.) A June 2024 JPPI Voice of the Jewish People survey (these surveys generally reflect the attitudes and opinions of more engaged American Jews) found that 66% of Jews who feel connected to Israel (which to a certain extent overlaps with engaged Jews and those affiliated with the organized Jewish community) felt closer to Israel as a result of Oct. 7. Forty-one percent said that these events increased the chances that they will visit Israel, and 82% donated to Israel. Eighty-nine percent of these connected Jews said they closely follow the Israel-Hamas war and identify with Israel’s public messages concerning it. A significant percentage of this population also supports Israel’s prosecution of the war; 89% strongly disagree that Israel is committing genocide.

2. Liberal/Progressive Diaspora Jews

Jews who are affiliated with the organized Jewish community and strongly connected to Israel constitute the dominant Diaspora group. But it is not the only group. Another group is becoming increasingly prominent among younger Jews for whom Israel is not an essential element of what being Jewish means to them. According to a 2020 Pew Research survey, about 16% of American Jews hold this position. However, according to the 2022 AJC survey, 43% of American Jewish millennials (25-40) hold this view. Those who say that Israel is not important to their Jewishness have a greater tendency to self-identify as liberals and/or Democrats. According to Pew and AJC surveys from 2021-23, those who identify as liberals or Democrats are much more likely to say that Israel is not important to their Jewish identity and/or that they do not have a strong emotional attachment to Israel.

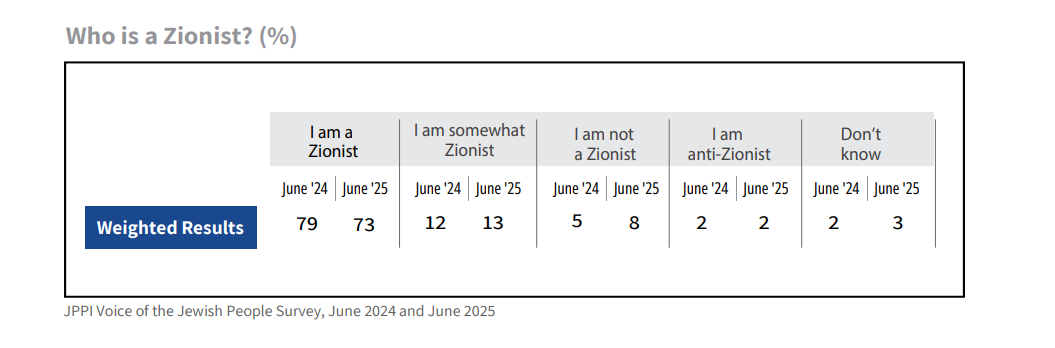

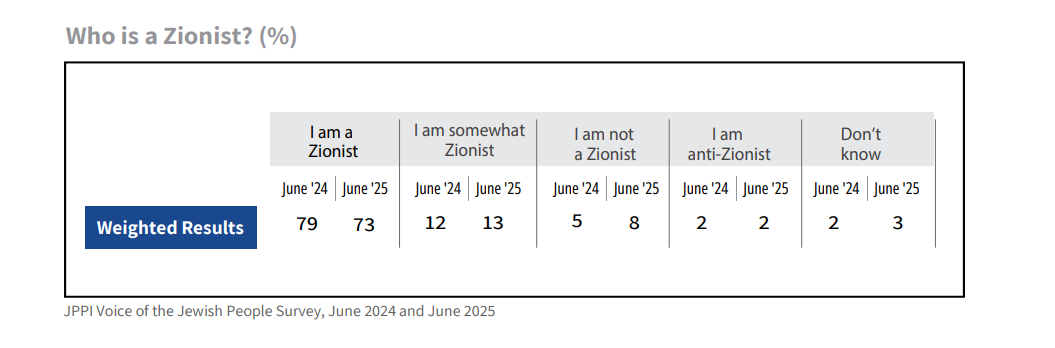

According to JPPI Voice of the Jewish People surveys from 2024-25, among those who reported not feeling connected to Israel, 92% said that they grew more distant as a result of Oct. 7 and the war. Eighty-eight percent said that they hadn’t donated to Israel since Oct. 7. Ideological orientation appears to directly correlate with one’s connection or lack of connection. Generally, those positioned at the more conservative end of the ideological spectrum reported feeling closer to Israel as a result of the events of the last two years. Trump voters reported a 50% increase in interest in visiting Israel post-Oct. 7.

Regarding the actual prosecution of the war, 32% of respondents self-identifying as strong liberals considered the Israeli response to October 7 too aggressive. By contrast, 50% of those who identified as conservatives felt it was not aggressive enough. Forty-two percent of respondents in the under-35 cohorts said that Israel’s military response to October 7 is “unacceptable.” Among respondents “not connected” to Israel, about half agree that Israel is committing genocide in Gaza.

In surveys of the general U.S. Jewish population conducted by the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs and JTA, between 22% and 30% believe that Israel is committing genocide in Gaza. Fifty-seven percent of Jewish Democrats are in favor of an immediate ceasefire in Gaza; the figure is 50% among the general Jewish population. American Jews, like other Americans, have become more sympathetic of the Palestinians in recent years. But only a small (if vocal) minority actually endorses the pro-Palestinian position. Thus, according to Pew Research from April 2024, 40% of American Jews have a favorable view of Palestinians (50% in the general population). With all that, only 10% of American Jews support BDS against Israel.³

Despite their claim that Israel is not central to their Jewish identity, 86% of Jews who said that they were not connected to Israel also said they followed the war very closely; among the connected, 89% said so.

This pattern of left-wing, liberal, or progressive political affiliation with disassociation from Israel and Zionism has a number of roots in Jewish intellectual and religious history. One of these sources is the idea that the Jews have a mission to the world that justifies continued Jewish existence. One of the most common ways of describing this mission is through the notion of ethical monotheism (Hermann Cohen) and the quest for social justice. Today, in liberal Reform and Reconstructionist circles, this is interpreted as the commitment to Tikkun Olam – universal values of human rights and pluralism. “Jewish values” in this context means commitment to human rights and equality (including gender and LGBTQ+ equality).

Another social justice tradition derives from early 20th-century Eastern Europe. Zionism was adopted in Eastern Europe as a solution to the suffering of the Jews as a result of antisemitism and persecution, but other solutions were also formulated and offered. Some of these attributed the persecution of the Jews to class factors and argued that with the establishment of a socialist or communist society, hatred of the Jews would disappear. These movements had many adherents among the Jewish immigrants to the United States and other countries (Canada, Argentina) in the first part of the 20th century. These movements were indifferent or hostile to Zionism and the establishment of a Jewish state.

Thus, we have a number of narrative traditions of Jewish identity that place social justice and human rights at the center of “Jewish values” and see themselves as belonging to liberal or left-wing organizations of the United States and other Diaspora countries. While the majority of non-Orthodox Jews combine a liberal political orientation with support for Israel, a combination that has become somewhat more difficult to sustain post-Oct. 7, a significant number have adopted non-Zionist or anti-Israel positions.

In recent years, especially after October 7, the rhetoric branding Israel as a “settler-colonial” society that oppresses Palestinians and practices apartheid and even genocide, has been adopted by some progressive and left-wing Jews and Jewish organizations. They have withdrawn support for Israel and in addition to criticizing its policies have begun to question its very existence. Jewish participation in pro-Palestinian demonstrations after October 7, although small, was highlighted by demonstration organizers and the media. Hence, the attitudes revealed in survey data are also reflected in Jewish organizational life.

Distancing from Israel and non-identification with it is also reflected in Jewish intellectual and cultural life. Intellectual criticism of Zionism and throwing the very existence of Israel into doubt has moved from the fringes of Jewish cultural life to become a fashionable cultural and intellectual theme as evidenced by the publication of anti-Zionist books by leading Jewish scholars and intellectuals such as Daniel Boyarin, Shaul Maggid, Peter Beinart, and Judith Butler. Similarly, anti-Zionist periodicals (e.g., Jewish Currents) have been given prominence and promoted by the mainstream media, such as the New York Times. These varied publications advocate a “Diasporist” (or Galuti) version of Jewish identity, saying that Jewish minority existence and even “powerlessness” is the fulfillment of Jewish life and awards Jews the moral authority to pursue social justice. Judith Butler has even affirmed that “Jewishness” is “the displacement of identity,”⁴ that is, it requires the self-annulment or erasure of one’s own identity. Some of these publications have published aggressively anti-Israel articles.

Israeli Jews and their Relation to the Diaspora

3. The Israeli “New Jew”

This group emphasizes Israeli sovereignty and self-reliance, (as well as economic productivity) while categorizing itself as a break from the “old Diaspora (Galuti) Jew,” who is viewed as weak, passive, and overly religious/separate. It contends that a Jewish nation-state is needed to be like everyone else and fit in with the global landscape, without needing to rely on others to protect or fight for them. This stream comprises in large part secular Israelis. Those who identify with this narrative often self-identify as first and foremost “Israeli” (36% – Pew), signaling a break with the old Galuti Jewish identity.⁵

The New Jew narrative was severely upset by the October 7 invasion and attack. The massacre, according to this narrative, was precisely what Zionism and Israel, with its armed forces, was established to prevent. October 7 called into question the entire Zionist enterprise, which was expressed in a variety of ways. One common expression of this was the use of the word “pogrom” to describe the October 7 onslaught. This word, with its connotations of the exile and Jewish helplessness, conveyed that October 7 was a regression to a pre-Zionist condition of Jewish misery. The popular (2014-2024) Israeli TV comedy series HaYehudim Baim (The Jews are Coming), which satirized episodes from Jewish history, included a sketch that framed Oct. 7 as part of a chain of Jewish catastrophes, including the destruction of the Temple and the infamous 1903 Kishinev pogrom.

The assimilation of Oct. 7 into the Galut experience was also conveyed in Holocaust comparisons and tropes, especially (Israeli) Jews hiding or being hidden by non-Jews. This shift squares with the feeling of closeness to Diaspora Jews reported by Israeli Jews in the wake of Oct. 7.

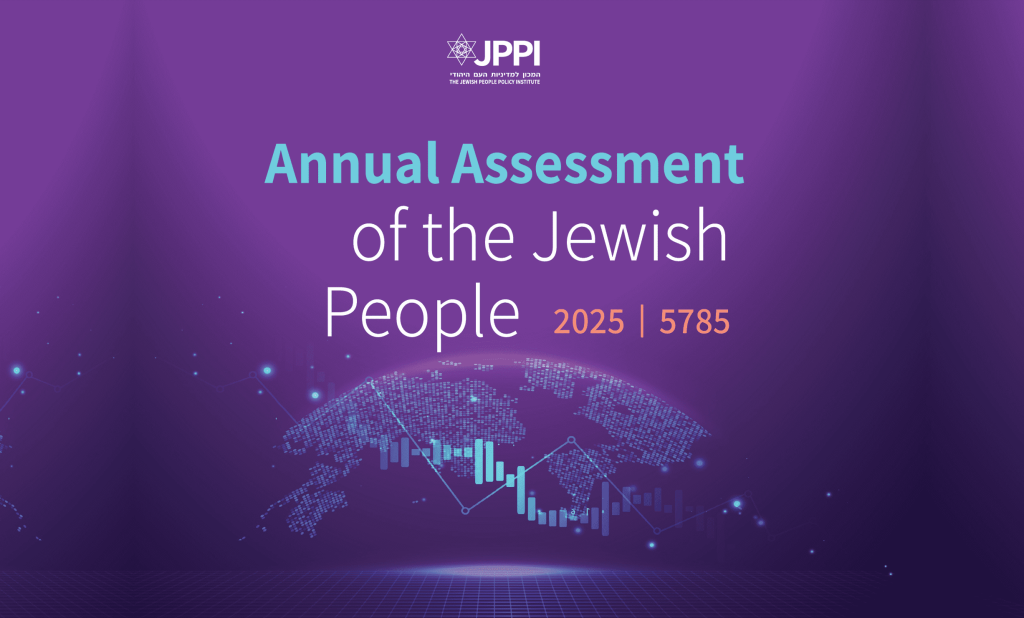

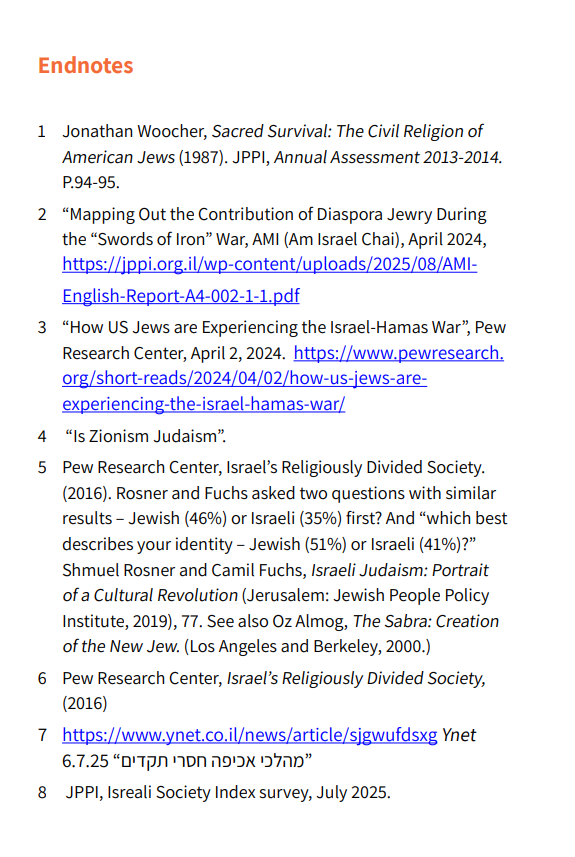

According to the Ministry of Diaspora Affairs January 2023 Diaspora Index measuring the ties of Israeli Jews to the Diaspora, 63% of Israeli Jews felt that Diaspora Jews were their brethren; by February 2025, this figure had risen to 71%. After Oct. 7, the overall Diaspora Index rose to its highest level ever – 5.92 out of 10 (the year before, it had registered 5.46). The most dramatic change was detected among the Hilonim (secular Jews), those who traditionally carried the “New Jew” orientation; the percentage who felt that Diaspora Jews were their brethren shifted from 36% in October 2020 to 56% in February 2025 – a 20-point shift upward. Perhaps this increased feeling of closeness to the Diaspora was informed by the fact that Israeli Jews, especially the Hilonim, became more circumspect in their view of themselves as superior, transformed “New Jews,” finding themselves in the “same boat” as Diaspora Jews, that is, as a vulnerable minority.

The paradox at the center of the relationship between Israeli Hilonim-New Jews and Diaspora Jews is that while there is ideological distance between them – the Israeli Jews regard themselves (mostly implicitly, even unconsciously) as a superior elite vanguard – the two groups resemble each other demographically and sociologically. Diaspora Jews (especially those in North America) and Israeli Hiloni New Jews are largely Ashkenazic, possess university-level educations, and are middle to upper-middle class. The ideological or symbolic distance between them decreased post-Oct. 7.

Israeli self-regard was somewhat restored by the phenomenally successful military campaigns against Hezbollah and Iran.

4. Israeli Ethno-Religious Nationalism

This narrative is represented by supporters of Israel’s current governing coalition and especially Likud voters. It thinks of Israel largely as a continuation of traditional ethno-religious Jewish communities and identity, empowered by military prowess and the mechanisms of state. It self-identifies first and foremost as “Jewish” (45% – Pew).⁶ Though, unlike traditional ethno-national and religious Jewish identity, it understands itself as a dominant majority, not a persecuted minority. It regards Orthodox Judaism as authoritative and authentic, though many of its adherents are not observant in the rigorous Orthodox sense. Among this group, Masorti (traditionalist) Jews are prominent, especially those of Middle Eastern and North African origins (Mizrahim).

This identity narrative suffered as a result of October 7 insofar as its representatives were in power at the time of the onslaught and held governing responsibility. It turned out that it was not as reliable as it had claimed to be in the area of security. The national loss of confidence in the current coalition can be measured by public opinion surveys, which have found (at least as of this writing) that it is likely to garner 44-48 Knesset representatives in the next elections as opposed to the 64-68 it has held since the government was formed in January 2023.

Despite the overall support that Diaspora Jews grant Israel, tensions have entered into the relationship between Diaspora Jewish leaders and organizations and the Likud representatives of the ethno-national stream in the Israeli government. This is due to the different positions of the two communities. In Israel, the Jews constitute an ethno-national majority that dominates the country. The ethno-religious nationalists who currently control the government place the interests of the Jewish ethno-national group above those of all other ethic and national groups in the country. They see themselves as aligned with other dominant ethno-national groups such as the Poles and the Hungarians. Further, they also see themselves aligned with other right-wing nationalist and populist governments. Many of these governments publicly support Israel, and Likud and Religious Zionism ministers (see below) therefore regard them as international allies who provide much-needed international support.

Diaspora Jews are an ethno-national minority in their countries of residence. In their historical memory, they suffered at the hands of ethno-national majorities, especially in Eastern Europe. This includes during the Holocaust, when local populations participated in the extermination of the Jews. They are especially wary of ethno-national majority political parties with a history of antisemitism.

These tensions reached an inflection point in March 2025 when the minister of Diaspora affairs and combating antisemitism, Amichai Chikli, convened the International Conference on Combatting Antisemitism. Far-right European politicians, such as Jordan Bardella of France’s National Rally party, were invited to speak at the conference, much to the chagrin of liberal Jews in Israel and abroad. Some of these politicians support Israel but are affiliated with historically antisemitic political parties, some of which continue to traffic in antisemitic tropes and language. The National Rally party, for example, under its former name, the National Front, was explicitly antisemitic and held admiration for the French Vichy regime, which had participated in the Holocaust.

Many Diaspora leaders condemned these invitations, saying that they were incompatible with combating antisemitism. In protest, several Diaspora leaders and organizations, including those dedicated to combating antisemitism, withdrew from the conference and/or called for its boycott. These included the AJC, the ADL, the World Jewish Congress, the European Jewish Congress, and the Conference of European Rabbis. Prominent Diaspora leaders who withdrew included Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mervis of the UK, the philosopher Bernard-Henri Lévy, ADL head Jonathan Greenblatt, and others.

5. The Haredi Narrative

The Haredi (ultra-Orthodox) Jewish identity narrative differs significantly from other Jewish identity narratives. It views itself as the “remnant of Israel.” That is, the part of the Jewish people that remained loyal to authentic Torah observance and has not been corrupted or contaminated by modernity. The most important aspect of its identity narrative is that it has separated itself from the Jewish mainstream. The Haredim maintain separate but parallel Jewish communal institutions, synagogues, schools, free loan societies, etc.

In Israel, the Haredi sector has developed along two contradictory paths. First, it has restricted, at least officially, its male population to Torah study exclusively. In so doing, they do not participate in the two most important activities of Israeli men – the military and the workforce. At the same time, the political parties representing them have become important partners in right-wing governments headed by the ethno-religious nationalist Likud.

With the Israel-Hamas war, they have entered into a paradoxical position. Despite the IDF’s growing manpower needs, the Haredim have laid out a vision of principled non-participation in the war effort. In fact, they have redoubled their efforts to obtain a blanket draft exemption for their population of 80,000 young men who could be candidates for military service. They have leveraged their importance to the survival of the current right-wing government by pushing for a law that would grant their otherwise conscription-aged men a permanent exemption from military service, Torah scholars or not. Israel’s other population sectors, including some coalition partners, have not cooperated with this aim and have even opposed it. In a survey taken in November 2024 by the Israel Democracy Institute 84.5% of the non-Haredi population favor Haredi conscription. (Likud voters shifted from 52% in favor before the war to 74% after Oct. 7, and Religious Zionism voters shifted from 51% to 79%.)

The IDF has been sending out conscription notices to draft-eligible Haredi men declaring that it will enforce “deserter” penalties on those who don’t comply.⁷ Faced with such opposition, the Haredim have engaged in disruptive street demonstrations (at least 16 large-scale protests since Oct. 7) and efforts to defend their ideology, while demanding strict adherence to it within the Haredi community.

The Haredi Jewish identity narrative has, to some extent, come under attack. In response, the Haredi leadership has attempted to shore it up, at least internally. Nevertheless, there are also reports of change within the Haredi community because of young men who have ventured from the fold and joined the IDF. A portion of the Haredi community now has personal ties to the Israeli military. It remains to be seen how substantial the change turns out to be.

In June 2025, two ministers from the Agudath Israel party resigned from the government in protest against the non-enactment of the law relieving Haredi males from military service. A month later, both the Degel HaTorah party and the Agudath Israel party (which together make up the United Torah Judaism alliance) left the governing coalition, and the Shas party announced that it too is leaving the coalition but would continue to support the government from outside the coalition.

The Haredim were the one group reporting less identification with Diaspora Jews. Perhaps this reflects an increased consciousness of their sectarian position and their apartness from the mainstream of the Jewish people, caused in part by the controversy surrounding their military conscription.

6. The Israeli Religious Zionists

Even though there are many sub-streams of Religious Zionism in Israel, its mainstream identity narrative (as understood through messaging in their sectorial educational system and media) is one of religiously inspired integral nationalism, in which the individual is rooted in the national collective and the national collective is considered to be rooted in the land and national territory. The ultimate aim of the Zionist enterprise, according to this ideological system, is to fully embed divine or Torah ideals in the national life of the Jewish state. The national territory – the Land of Israel, (including the West Bank and Gaza) is the necessary material sub-structure that enables this. The national collectivity (the People of Israel) and the national territory (the Land of Israel) are regarded by Religious Zionists as unitary entities. Hence, the Land of Israel cannot be forfeited or divided, and individuals are rooted to the national collectivity in their very being. Religious Zionists (along with other right-wing elements in Israel) do not recognize that Palestinians have any legal or moral right to the Land of Israel. The presence of Palestinians does not constitute a moral issue or dilemma, but rather poses a practical security threat.

One practical outcome of the individual’s sense of rootedness in the collective is their willingness to sacrifice themselves for the achievement of collective goals – in the Israel-Hamas war. Religious Zionists, who constitute 16-17% of the general population, are over represented in combat units relative to their population share. This is especially true in elite units and in the combat officer corps, where they make up between 30 and 40%. While there are no official figures regarding the religious or political identity of those killed or wounded in the war, most observers are under the impression that, here too, their casualty rates are higher than their share of the population.

Their high combat participation rate has certainly earned Religious Zionists a certain amount of admiration and prestige. Still, their attitudes regarding certain important national questions differ significantly from other sectors of the Israeli population and other voices in the public discourse. One key issue concerns the hostages abducted on Oct. 7. While the families of many of the hostages and a substantial and vocal portion of the Israeli public and media endorse a deal to free the remaining hostages even if it means ending the war, many Religious Zionists, including the sector’s political leadership, Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich and Minister of National Security Itamar Ben Gvir, actively oppose such a deal. This attitude, too, is based upon their understanding that individuals must subordinate themselves to collective needs. By contrast, those endorsing a hostage deal cite the social contract between individuals and the state: In exchange for mobilizing for the collective good, the state will safeguard the individual’s interests, even at the state’s expense. These groups argue that the social solidarity that would be expressed by a hostage deal is one of Israel’s greatest assets.

The Jewish Israeli public seems to be evenly split on this issue. Around half say they would support such a deal even if it means leaving Hamas in power; the other half would reject such a deal⁸.

There is much less agreement around the Religious Zionists’ war aims. Ministers Smotrich and Ben-Gvir openly say they want to impose IDF military rule on Gaza, annex it, and renew Jewish settlement there. Among those who voted for the right-wing ruling coalition, 60% support such a policy. It is estimated that among Religious Zionists, a similar number supports it. However, among the entire population, such a policy is supported by only 22-33% (42% among all Jewish Israelis).

The Religious Zionist sector is ideologically committed to ties with the Jewish Diaspora, as it views the global Jewish population in traditional terms – as a single ethno-religious-national entity. While in recent years such religious thinkers such as Diaspora Rabbis Joseph B. Soloveichick and Lord Jonathan Sacks have gained followings among Israeli Religious Zionists, for the most part, they tend to view Diaspora Jews as a manpower reservoir for Aliyah and settlement projects. October 7 and the ensuing War have not substantially affected their identification with Diaspora Jews.

Public statements by political leaders of the “Religious Zionist” parties on the war and the future of Gaza, such as Smotrich’s calls for the forced expulsion of the Gazan population, the utter destruction of their cities (echoing the biblical call for the destruction of Amalek), and starving the population until the hostages are returned, have caused Diaspora Jews extreme discomfort. As a result, major Jewish organizations like the Council of Presidents of Major Jewish Organizations have condemned Smotrich and Ben-Gvir and disavowed their inflammatory statements. These organizations have called on Jewish communities to boycott Smotrich and deny him a platform from which to speak. Ben-Gvir’s April 2025 U.S. visit sparked angry protests at Yale, at the Capitol, and in New York. These incidents, too, exacerbated tensions between the attitudes of Israeli nationalist politicians and Diaspora Jewish leaders.

The events of October 7, 2023 and the Israel-Hamas war that followed have certainly had a galvanizing effect on the relationships of Diaspora Jews and Israel. But this effect was not unidirectional. In the Diaspora, it strengthened the ties to Israel of the mainstream Jewish Diaspora communities, but it also helped propel the anti-Zionist narratives of certain progressive and left-wing groups. In Israel, it weakened the “New Jew” identity narrative of the Israeli Sabra Hilonim, resulting in enhanced identification with Diaspora Jews. At the same time, it brought out the tensions between a majority ethno-nationalist identity and a minority Diasporic ethno-religious identity. These tensions were thrown into sharp relief by the May 2025 International Conference on Combatting Antisemitism held in Jerusalem and sponsored by Diaspora Affairs Minister Amichai Chikli. The extremist statements by the “Religious Zionist” Ministers further sharpened and amplified these tensions, resulting in unprecedented calls by Diaspora Jewish organizations to boycott Israeli government ministers.

Policy Recommendations

- The “Diaspora perspective” should be better represented in Israeli decision-making. The best avenue for this is the Diaspora Affairs Ministry and the Knesset Diaspora Affairs Committee. Formal committee hearings in this regard should be held twice a year with representatives from the Diaspora attending.

- The Ministry of Diaspora Affairs should establish a permanent position of Diaspora Adviser to the Minister, mandated by legislation. The legislation should also specify the issues on which the Diaspora Adviser must be consulted. The position should be held (appointment process to be determined) by a leading Diaspora figure.