Zionism: The People of Israel Enjoying the State of Israel in the Land of Israel

Zionism: A Thrice-Born Movement

״To be a free people in our homeland, the land of Zion, Jerusalem….״ This, Hatikvah׳s final line, concludes the Jewish national anthem – or is it the Israeli national anthem? The answer is ״yes, both.״ That blurring tells the story of the Jewish people, Zionism, the Jewish national movement, and Israel. The Jewish national homeland, Israel, is also a Jewish-democratic state that guarantees the equal rights of the 20% of its citizens who are not Jewish.

Jews confuse. Had followers of Judaism, the Jewish people׳s religion, launched Judeanism, and established a Jewish-democratic state of Judea, enemies couldn׳t convincingly say: ״I love Jews but I hate Judea and Judeanism.״ It would be like claiming: ״I love Italians, but I hate Italy, Italian food, and the Italian language.״

But history happens. Different words emerged. The religion of Judaism defines Israel, the Promised Land, as the Jewish people׳s ancestral home and forever headquarters. Over the centuries, Zion, a central mountain in Jerusalem, the Jewish people׳s 3,000-year-old capital, became a central symbol to the Jewish people. That׳s why the movement to launch the Jewish state, formed in the late 1800s, called itself Zionism. In 1948, David Ben-Gurion, the first prime minister of the re-established Jewish State, declared the new State of Israel.

Still, consider Zionism a thrice-born movement.

Zionism’s First Birth: Ancient Roots Biblically, Archaeologically, Existentially

First, in the Bible, Abraham and Sarah intensify their religious journey into Judaism by moving to the Jewish homeland, the Land of Israel, somewhere between 2100 and 1900 BCE. That leap begins the Jewish people׳s journey into history. From then on, whenever they – and their ancestors – left the Jewish people׳s home, they defined themselves as in ״exile.״ Four thousand years later, even after centuries with most but not all Jews scattered worldwide, whenever Jews pray, wherever they live, they turn toward Zion.

Originally, Judaism was heavily land-based. Jews usually worshipped God through agricultural sacrifices, especially at the Holy Temple in Jerusalem. Even as Judaism became more abstract, even as conquerors displaced the Jews, the land remained central to Judaism theologically and the Jewish people symbolically. The Talmud teaches: ״Living in Israel is equivalent to all the Torah׳s mitzvoth, commandments.״

While the Jewish people suffered when enslaved in Egypt, they thrived three centuries later with their harp-playing, Psalm-writing, charismatic King David around 1000 BCE. David gives the Jewish people the eternal gift of Jerusalem, their capital.

By building the First Temple there, David׳s son King Solomon harmonized Jewish political and spiritual power. In a simple, agricultural society, the Second Temple sent people׳s spirits soaring. Towering at 45 meters during Herod׳s days, it was almost as tall as today׳s White House. During the three pilgrimage festivals of Pesach, Shavuot, Sukkot – Passover, Pentecost, and Tabernacles – Jews gathered from all over the world, fulfilling the Torah׳s vision.

Today, when Jews read the Temple Service on Yom Kippur, or wave the Lulav (palm fronds) described in Leviticus 23:40, or end the Passover seder singing ״Next Year in Jerusalem,״ those rituals celebrate their tie to one homeland, Israel.

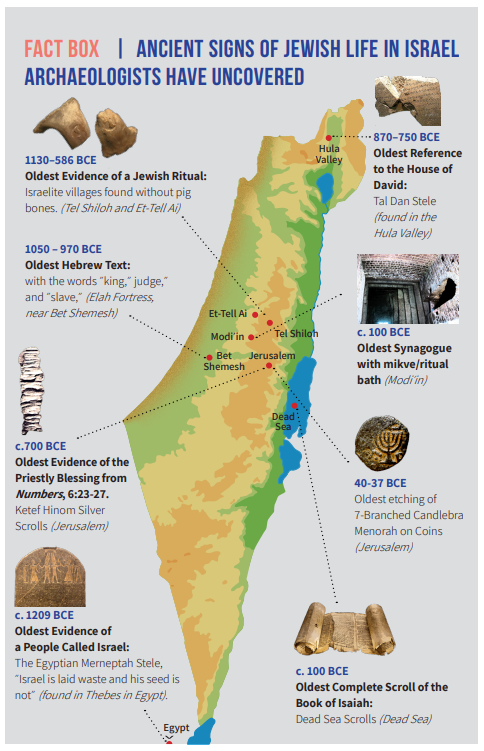

Archaeological evidence confirms Jewish life in Israel. A 2,700-year-old amulet found in Jerusalem includes the priestly blessing from Numbers, 6:23-27: ״May the Lord Bless you and keep you….״ The etching of a seven-stemmed menorah candelabrum in Migdal, in the Galilee, was dated to 2,000 years ago, during Second Temple times. The Dead Sea Scrolls include 2,000-year-old Biblical parchments and tefillin – phylacteries. Certain villagers during the Iron Age IIB – 925 to 586 BCE, the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah – left no chewed pig bones behind for archaeologists, unlike their neighbors. That makes avoiding pork, keeping the kosher dietary laws, the most ancient Jewish ritual confirmed by secular archaeologists.

Most striking are the Holy Temple׳s remains, the 2,000-year-old Western Wall. More than ten million people a year visit the Second Temple׳s outer wall in Jerusalem. Nearby, in the City of David, archaeologists uncovered the ״Pilgrim׳s Way,״ which worshippers walked during the festivals. Preachers like Jesus of Nazareth probably stood along that path, using its stone stands as podiums.

Archaeologists also uncovered evidence of the destruction of both Holy Temples. Charred wood dating back 1,955 years, along with daggers and coins, testify to the calamities once-free sovereign Jews endured, by the Babylonians in 586 BCE and again in 70 CE by the Romans. Jews still end wedding ceremonies by breaking a glass, symbolizing the destruction of Jerusalem that still haunts Jewish life, even at joyous moments.

The Babylonian exile lasted 40 years; the Roman takeover proved more enduring. By 132 CE, the Emperor Hadrian, insulting the Jews after too many revolts, renamed the land ״Syria Palaestina.״ Jerusalem became ״Aelia Capitolina.״ As the Roman Empire became the Christianized Byzantine Empire, Jerusalem became a popular takeover target. The Muslims, Christian Crusaders, Mamluks, and Ottomans came and went. Despite many Jews being exiled worldwide, some Jews remained in their homeland, particularly in Israel׳s four holy cities: Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed, and Tiberias.

While exiled, the Jewish people remained a people apart – often ghettoized, following their laws, respecting their leaders, caring for their poor. Christian and Muslim contempt isolated the Jews – while Jews communicated with one another globally through trading, kinship, and rabbinic teachings. And, wherever they were, Jews kept looking toward Zion, dreaming of redemption.

Zionism, then, is catalyzed by positive kinetic forces shaping Jewish identity and the need to be a free people back home after centuries of suffering. Yearning to return, Jews kept praying toward their homeland. Over the centuries, some reached the Promised Land. Still, the Zionist movement needed restarts, beyond its biblical spawning and Medieval stumbles.

Zionism’s Second Birth: Defining Nationhood

First, in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Enlightenment and Emancipation freed some Jews from the European ghettos. But Jews were mugged by modernity. Acceptance into ״enlightened״ society usually involved concealing your Jewish self.

Starting in Germany in the 1810s, the movement of Reform Judaism triggered an intense debate about how to modernize. Originally, Reformed Jews distanced themselves from some of the traditional foundations of peoplehood and homeland. Three decades later, the Conservative movement committed to rooting its changes in a more evolutionary, historical process. Meanwhile Orthodox Jews declared themselves most adverse to change. Today, other denominations and ideological spin-offs have joined this ongoing 200-year-old debate.

Watching Italians form an Italian consciousness, Brits create a United Kingdom, and Americans develop liberal-democratic nationalism, some Jews updated the traditional Jewish national consciousness.

Then, modernity betrayed its own promises, unleashing waves of Jew-hatred. The Russian pogroms – anti-Jewish riots – of 1881-1882 and the rise of populist nationalist antisemites in Austria, France, and Germany inspired a few Jews to move to Palestine. Most Eastern European Jewish immigrants went to America. Other thinkers began articulating a Jewish nationalist vision.

The Jews in the East felt less betrayed because their expectations were lower — no modernizers promised Enlightenment. Fewer Jews in Muslim and Arab lands rebelled against the rabbis, assimilated, or tried fitting in by draining their Judaism of its nationalist, peoplehood, dimensions. That׳s why many scholars say that the Jews of Muslim and Arab lands were ״born Zionist.״

Ideologically, the small, gutsy band of European Jewish thinkers and activists pioneered a modern liberal-democratic Jewish nationalism on the biblical commitment to a land-centered identity. Pragmatically, the Zionist movement coalesced as the 19th century ended.

In 1878, before the pogroms, religious Jews established Petah Tikvah – Gates of Hope – Palestine׳s first modern Jewish agricultural settlement. In 1882, members of BILU (a Hebrew acronym that translates into English as House of Jacob, let us go), intent on cultivating the Holy Land, responded to the pogrom-bred despair with hopes. Updating Judaism׳s one-line affirmation of monotheism, they proclaimed: ״Hear O Israel! The Lord is our God, the Lord is one, and our land Zion is our only hope.״

In 1890, the Viennese anti-religious rebel Nathan Birnbaum named this growing, old-new movement. The coalition of Russian-Jewish post-pogrom organizations called themselves ״Hovevei Zion,״ sometimes ״Hibbat Zion,״ ״lovers of Zion.״ Birnbaum translated the names into German as ״Zionismus,״ which became Zionism.

Zionism’s Third Birth: Seeking Statehood

In 1897, a 37-year-old journalist, ex-lawyer, and frustrated playwright boldly invited 208 delegates to a Zionist Congress in Switzerland. In Basel that August, Theodor Herzl established the formal Zionist movement in pursuit of Jewish statehood in Palestine. Zionism׳s three pillars – the land of Israel, for the people of Israel, establishing a State of Israel – grounded what became an extraordinarily successful movement.

Using the Congress to model his ideal vision of ״altneuland,״ old-new land, Herzl launched a Janus-faced movement. Zionism cherished the Jews׳ rich past while launching them into the future. Decades before political scientists discovered the power of ״pluralism,״ he invited representatives representing a range of Jewish ideologies, from religious to secular. And 74 years before women received the right to vote in federal elections in Switzerland, the Zionist Congress in Basel empowered women delegates with equal voting rights and leadership opportunities. From the start, this Jewish-democratic movement sought a Jewish-democratic state. Zionism׳s Jewish traditions gave it an identity; its democratic character ultimately mobilized the Jewish masses and created a ״New Jew״ to make it work.

Israel was established in 1948, joining the post-colonial wave of new countries following World War II. But most former colonies in Africa and Asia became dictatorships. Zionism freed its people to live in their land, enjoying democratic civil liberties and the right to vote.

Despite its impressive ability to change history and its remarkable focus on building a Jewish state in Palestine, the Zionist movement always included intense political rivalries and searing debates. Six different schools of Zionist thought emerged: their clashes still echo in Israeli politics today.

- Theodor Herzl׳s Political Zionism emphasized building a Jewish-democratic state, accepted by the international community.

- David Ben-Gurion׳s Labor Zionism added a Socialism-friendly egalitarian dimension, inspiring today׳s attempts to mix all kinds of different ideologies with core Zionist values.

- Ze׳ev Jabotinsky׳s Revisionist Zionism combined a commitment to liberalism and individualism with an impatience to get a state immediately, given Europe׳s growing Jew-hatred. Today׳s Start-up Nation has its roots in Jabotinsky׳s liberalism.

- The Religious Zionism of Rabbi Abraham Yitzhak Kook reaffirmed the Jewish national movement׳s links to the Bible and the Jews׳ mystical connection to the land.

- Ahad Ha׳am׳s Cultural Zionism cultivated a linguistic, artistic, literary, and music renaissance fueling the national revival, with Jews worldwide finding inspiration and empowerment from their renewed homeland.

- In America, especially, the Diaspora Zionism of Henrietta Szold developed a philanthropic, support-oriented Zionism reconciling American patriotism with Jewish nationalism.

Today, Identity Zionism unites Jews all over the world by responding to the modern crisis of ״anomie,״ of loneliness, drift, and purposelessness. Zionism roots Jews in a 3,500-year-old narrative of a return to their land, their roots, their tradition, while building a forward-looking democratic community too.

Zionism Today: Being, Belonging, Becoming

Zionism is a noun and a verb. As a noun, Zionism denotes the movement that established the State of Israel in 1948. Since then, it is the movement to defend Israel and the Jewish people when necessary, but build Israel, be built by it, and fulfill individual and communal dreams, always. The sentence׳s second half makes Zionism a verb, describing a process of not just being but of becoming: from the weak, homeless, persecuted Jew to the strong, rooted, democratic Jew returning to history; from the thinking and believing Jew in exile to the thinking and believing and acting Jew of today, wherever Jews live, expressing a range of religious and political beliefs while sharing an ironclad commitment to the Jewish people and the Jewish state.

Before 1948, Zionism had to convince others – including many Jews at first – of three Zionist assumptions. First, because the Jews were a people, not just co-religionists, Jews had national rights to statehood. Second, there was only one logical place to establish that state. And third, Jews needed a Jewish state, to end Jewish suffering while fulfilling Judaism and resurrecting the Jewish people. Three decades before becoming Israel׳s first president, Chaim Weizmann insisted that the Jewish people ״never based the Zionist movement on Jewish suffering.״ Instead, the ״foundation of Zionism was, and continues to be to this day, the yearning of the Jewish people for its homeland, for a national centre, and a national life.״

When a British aristocrat sniffed, ״Why do you Jews insist on Palestine when there are so many undeveloped countries you could settle in more conveniently?״ Weizmann, Zionism׳s quipmaster general, snapped: ״That is like my asking you why you drove 20 miles to visit your mother last Sunday when there are so many old ladies living on your street?״

Still, there was a robust debate in the Jewish world about Zionism. While some extremely religious and extremely secular anti-Zionists rejected Jewish nationalism, many non-Zionist Jews were simply skeptical. Some doubted the chances that a viable state would emerge. Some feared accusations of ״dual loyalty״ in their homes away from the homeland. And many defined Judaism as a religion, treating Zionism as marginal and idiosyncratic. Today, the overwhelming majority of Jews are Zionists.

The horrors of the Holocaust, followed by the extraordinary successes in establishing and defending the Jewish state, transformed the Jewish conversation – as well as the Jewish map. Most dramatically, Reform Judaism Zionized, embracing peoplehood and statehood. In 1949, Rabbi Arthur Hertzberg marveled in Commentary magazine that Zionism had also succeeded ״in achieving around itself… a startling unanimity of Jewish opinion.״ From 1945 to 1948, ״there was about Zionism the compelling atmosphere of a moral crusade in which all of world Jewry participated.״

Today, nearly, 80 years later, supporting Israel and being Zionist has become a consensus position among most Jews, Over 80% of American Jews support Israel, while communities in France, Australia, and other countries reflect even higher percentages. Nevertheless, in the United States and Great Britain, there is a growing number of non-Zionist rabbis, professors, and communal leaders. Neither anti-Zionist nor antisemitic, they view Diaspora Jewish life as more likely to fulfill Jewish values and keep Jews alive. Most don׳t support the modern State of Israel ideologically, but don׳t question its right to exist. It׳s ironic – few Zionists today negate the Diaspora, as many did decades ago; but some leading Diaspora thinkers and activists now justify themselves by negating Zion.

Four Tracks to Modern Zionist History: Legitimizing the State, Building it, Filling it, then Living the Dream

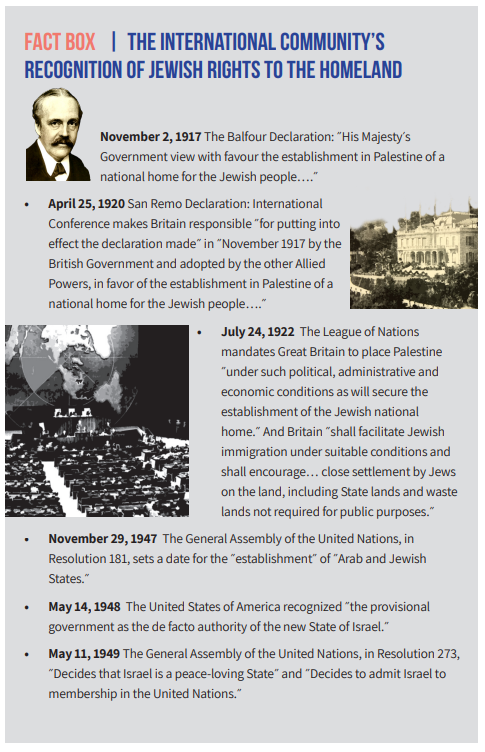

In the 20th century, Zionists sought international recognition, built an infrastructure for the state, populated it with citizens, then sought to live the Zionist dream. Diplomatically, key dates start with the 1917 Balfour Declaration when Great Britain recognized the need for a ״national home for the Jewish people in Palestine.״ The 1920 San Remo Conference, recognizing Jews׳ rights to Palestine, culminated in the League of Nations׳ 1922 British Mandate for Palestine. Finally, with UN Resolution 181 in 1947, the international community validated Zionism, recognizing the Jews׳ rights to a ״Jewish state״ on their homeland.

The Jews didn׳t need international recognition of their historical rights to the land – but it helped. The UN made Zionism among the most legitimized of national movements, in contradistinction to today׳s international delegitimization campaign.

More important than external recognition was the internal state-building process. From resurrecting the Hebrew language to developing a powerful labor movement, Zionists created frameworks and institutions. Those achievements meant that when the state formally began in May 1948, the newly named ״Israelis״ didn׳t have to start from scratch. They were culminating a process, not jumpstarting it. Israel emerged as a democracy, with an economy capitalist enough to allow private property and free enterprise, but socialist enough to keep the state strong and its economy centralized, especially in the first few decades.

Wave after wave of immigrants bolstered the small Jewish population that had maintained the Jewish presence in the Land of Israel since the Romans. As Palestine׳s Jewish community grew and prospered, and the British modernized Palestine, Arabs started flocking there too. While there were 200 to 300 Arab villages before 1841, another 50 or 60 were established over the next century. Overall, the population jumped – by 36.8 percent from 1922 to the 1931 census. The Muslim population increased by 28.6 percent. The Jewish population nearly doubled.

Clearly, history moves. That should make territorial compromise possible. Populations shift. Borders change – six times for Palestine, later called Israel, in the 20th century alone. Only fools or fanatics talk about ״the״ historical borders of Israel or claim that every Palestinian Arab had been rooted in ״the land״ forever.

An Arab adage teaches: knife sharpens knife. Zionism׳s rise triggered Arab anti-Zionism too. Arabs rioted most violently in 1920, 1921, and 1924, culminating in the Hebron massacre of August 1929, when neighbors killed at least 67 Jews, raping, maiming and beating hundreds of others. In fleeing, Jews ended a long chain of life in Hebron stretching back at least to 1540.

Arab violence pressured the British to limit immigration in 1936 and 1939, just as Hitler׳s war against the Jews was building its deadly momentum. After World War II, tens of thousands of Jews were smuggled in as part of ״Aliyah Bet״ (the second Aliyah) bypassing British immigration restrictions until Israel emerged in 1948. The once-marginalized Zionist movement reoriented Jewish history, restoring the homeland to the center of Jewish life. By May 1948, 600,000 Jews were already living in the new State.

- RETURN HOME: Reestablishing Jewish sovereignty in the Jewish homeland.

- INGATHERING EXILES: Integrating three million immigrants since 1948 into the initial population of 600,000.

- EMPOWERMENT: Returning the Jews to history: From Victims to Actors

- JEWISH-DEMOCRATIC: Building a hybrid, Western-style capitalist democracy with a strong Jewish flavor.

- ALTNEU/OLD-NEW REVIVAL: Revitalizing Jewish secular and religious life while serving as a bastion of Western culture, with a high quality of life.

- THE HOLY TONGUE LIVES: Resurrecting Hebrew as a living language.

- JEWISH PEOPLE POWER: Creating a proud Jewish Diaspora inspired by the ״old-new homeland.״

Since the state׳s establishment, as Jews learned to live together and with others in their own country, Zionism evolved. The movement strengthens two distinct but overlapping entities: the Jewish people and the State of Israel. The Israeli author A. B. Yehoshua explained: ״A Zionist is a person who accepts the principle that the State of Israel doesn׳t belong solely to its citizens, but to the entire Jewish people.״

As Israel׳s builders steadied the state, from 1948 to 1998, their second-stage Zionism revolved around the questions: ״What kind of nation should Israel be?״ and ״What kind of people should the Jews become?״

In today׳s third stage, with Israel prosperous, thriving, yet still assailed, Zionism׳s torchbearers are clarifying three politically unpopular assumptions: First, the Jews׳ status as what the philosopher Michael Walzer calls ״an anomalous people,״ with its unique religious and national overlap, does not diminish Jews׳ collective rights to their homeland or the security and legitimacy every nation-state deserves. Second, the Palestinians׳ ties to the land do not negate the Jewish title to Israel: Americans, Canadians, Australians, and others also live with clashing land claims. Third, Israel juggles different missions: to save Jewish bodies and redeem the Jewish soul, while allowing all its citizens to thrive.

As Israel approaches its 80th birthday, it׳s time to resist telling Zionism׳s history through Israel׳s wars, despite the ongoing threats from its neighbors. The most famous dates in Israeli history remain 1948, 1956, 1967, 1973, and now, October 7, 2023. This war-to-war story gets punctuated by peace processes and terrorism. But this narrow reading defines Israel only through the lens of the Arab-Israeli conflict. Telling Israel׳s story through the decades, from the 1940s to the 1950s on to the 2010s and 2020s, American-style, adds politics, culture, demography, and economics to the mix. That approach highlights Zionism׳s seven great achievements – along with ongoing challenges.

- First: reestablishing Jewish sovereignty in the Jewish homeland. Jews today take this revolution for granted, but the ״wandering Jews״ returning home after nearly 2,000 years remains an extraordinary national comeback. The challenge now is keeping Israel just and safe.

- Second: integrating three million immigrants since 1948 into the initial population of 600,000, especially Holocaust survivors, refugees from Arab lands, Ethiopian Jews, and Soviet Jews, while preserving civil liberties and free immigration as the Middle East׳s only democracy. Simultaneously, a need for national solidarity keeps clashing with tribal identities, agendas, and sometimes furies.

- Third: returning the Jews to history, transforming the Jews from the world׳s victims to fellow actors on the global stage, spawned great opportunities and complex dilemmas. Learning how to wield power morally remains challenging.

- Fourth: building a hybrid, Western-style, capitalist democracy with a strong Jewish flavor. That mix reflects Zionism׳s fusion, blurring religion and nationalism. Israel is democratic enough to have Arab judges and politicians, but Jewish enough to celebrate Passover and Hanukkah publicly. Balancing traditional and particularistic impulses with liberal-democratic values is still confusing.

- That political mix sparked the fifth miracle, the social-cultural ״altneuland״ – the old-new land Theodor Herzl envisioned – revitalizing Jewish secular and religious life while serving as a bastion of Western culture, with a high quality of life. Still, it׳s hard to preserve the sense of us-ness in an age of me-ness.

- This Jewish cultural revival relied on the sixth achievement, resurrecting Hebrew as a living language. This act of linguistic resurrection was a Zionist act of national renewal. Of course, in a state with 20 percent non-Jews, the Hebrew culture must welcome other voices too.

- Finally, the Jews׳ renaissance in their homeland bubbled over, creating a proud Jewish Diaspora. The ״New Jew״ the Zionists imagined exorcised the broken-down, weakling within, across the Jewish world. Israeli power and pride encouraged Jews to assert themselves politically and made Jews more comfortable in their own skin. Identity Zionism builds on that pride and continues to inspire, although many are distracted by focusing on Israel advocacy rather than identity-building.

Over a century ago, in different times, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis observed: ״The great quality of the Jews is that they have been able to dream through all the long and dreary centuries. . . .״ Zionism gave – and still gives – Jews ״the power to realize their dreams.״ Still, decades later, when asked if his young State had fulfilled all his Zionist dreams, David Ben-Gurion answered, ״Not yet.״ This ״not-yetism״ is the catalyst for Zionist can-do idealism – and, admittedly, explains the disappointment of some Jews with Israel.

Aspirational democracies, like Israel, like America, keep balancing their most ambitious dreams, individually and communally, with the humility that comes from never quite achieving them. The key is to use high ideals to keep doing better, without being overly frustrated by the shortfalls – or too convinced of your own righteousness.